Charlie Chaplin was ridiculed and denigrated when he didn’t volunteer to fight in the First World War. It was only after his death that the world realized how great a service he did by choosing the film studio over the battlefield.

The Tramp, Chaplin’s most memorable character which later went on to become an icon of world cinema, hit the screen for the first time in 1914. And it didn’t take long for the character to attract worldwide popularity during the era of silent film.

Be it cinema screen or billboards, songs or comic strips, toys or adverts, the Tramp was everywhere. Crowds would clamor to go to the cinema to watch the character’s antics.

Owing to the widespread popularity of his slapstick, Chaplin became a famed, universally-loved figure of his time at the age of just 25. His films, treated no less than a miraculous medication, were regularly shown to the injured soldiers of the First World War.

The projectors were fitted in such a way as to project their images onto the ceilings of the hospitals, allowing bedridden soldiers to enjoy Chaplin’s films without having to sit up. The soldiers used to forget their emotional and physical trauma once they started watching the Tramp and his gags.

Laughing helped reduce the sufferings of the war-wounded soldiers. As Chaplin puts it, “Laughter is the tonic, the relief, the surcease for pain.” Chaplin’s universal medicine of laughter entertained and cured a worldwide audience since it transcended the barriers of language.

It was just a matter of time before the issue of Chaplin not enlisting was dramatically inflated by almost all media outlets. The little Tramp became the favorite target for cartoonists and journalists mainly because Chaplin’s rise to fame coincided with the outbreak of war.

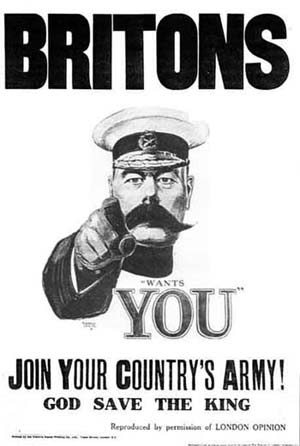

Chaplin, a British citizen working in the US, was ridiculed for not enlisting in either the US or the UK military. The leading media outlets of the time used to call him a “slacker.” The pressure increased significantly after the US joined the war on April 6th, 1917. That was when thousands of people sent angry letters and white feathers to Chaplin to shame him into fighting.

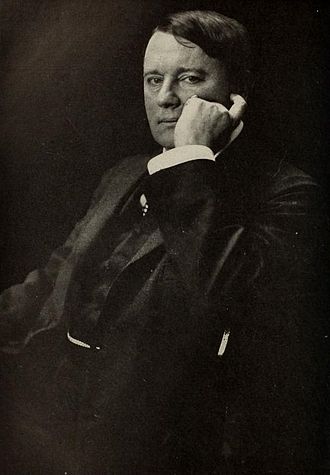

The smear campaign directed at shaming Chaplin for his failure to enlist was spearheaded by British press mogul Lord Northcliffe, the founder of the Daily Mail. Northcliffe reprimanded the actor numerous times in his publications, often demanding his immediate return to Britain.

For instance, Northcliffe’s Daily Mail severely attacked Chaplin in March 1916 for a war-related clause in his contract with a production house, Mutual Film Corporation. The war risks clause noted that Chaplin must not return to his native land for the duration of the war.

Another time, Northcliffe castigated Chaplin in a Weekly Dispatch editorial in June 1917, writing: “Charles Chaplin, although slightly built, is very firm on his feet, as is evidenced by his screen acrobatics. The way he is able to mount stairs suggests the alacrity with which he would go over the top when the whistle blew…

“In any case, it is Charlie’s duty to offer himself as a recruit and thus show himself proud of his British origin. It is his example which will count so very much, rather than the difference to the war that his joining up will make. We shall win without Charlie, but (his millions of admirers will say) we would rather win with him.”

Northcliffe’s aggressive bullying tactics kept intensifying over time. At last, Chaplin had to register himself with the US armed forces to save his reputation. He also gave a whopping $250,000 to the US and Britain for war activities.

Like other British nationals living abroad, Chaplin waited for permission from the British embassy, which supported his explanation, saying: “We would not consider Chaplin a slacker unless we received instructions to put the compulsory services law into effect.” Similarly, the soldiers also didn’t consider the actor a slacker. According to David Robinson, Chaplin’s biographer, the attacks “certainly did not come from servicemen.”

Though Chaplin had enlisted himself for the US military draft, he was rejected for being underweight and undersized. Unfortunately, the slacker attacks still continued, and people kept sending him white feathers.

Chaplin, a confirmed pacifist, later directed his efforts to end the war sooner, especially when he realized how he could utilize his stardom for political purposes. By that time, the Hollywood icon had enough money and a studio to do whatever he wished.

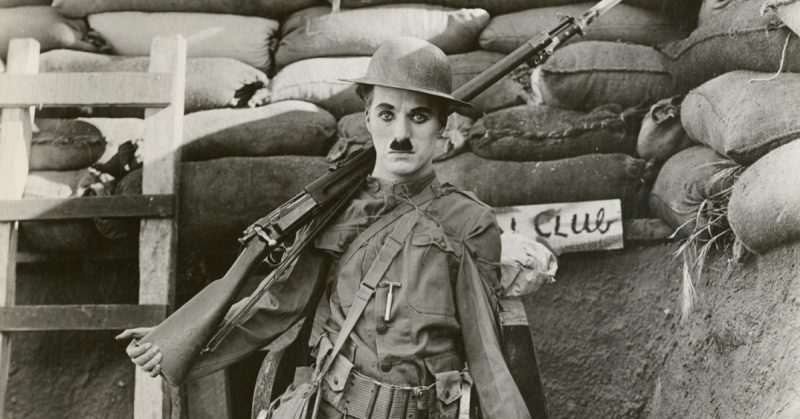

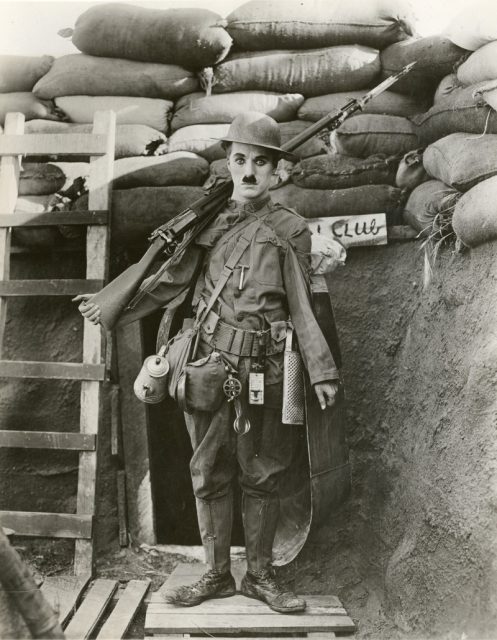

And that’s when his anti-war comedy, Shoulder Arms, hit the cinema. Released in May 1918, the film presented a sarcastic but funny overview of the war. It featured the Tramp in an army camp as an awkward rooky who has to face several challenges in order to survive the deadly trenches.

He is seen battling the dirty mud, the flooding, the persistent fear, and the grossly bad food. The Tramp eventually captures the Kaiser after he disguises himself as a tree trunk and crosses no man’s land in his hilarious camouflage.

Chaplin’s anti-war sentiments only increased with time as his political clout strengthened later in his career. “Though he might make comedy from it,” Robinson writes, “the folly and tragedy and waste of war were always to bewilder and torment Chaplin.”

Besides war, Chaplin also spoke against militarism and nationalism, most famously in The Great Dictator. The 1940 film was seen as pro-Communist propaganda by the critics because it mocked Mussolini and Hitler but didn’t target Stalin. Chaplin was branded Communist and hence began a new struggle – one that wouldn’t leave him until his death.

“I am not a Communist. I am a human being, and I think I know the reactions of human beings,” Chaplin said while addressing the American Committee for Russian War Relief in San Francisco in 1942. “The Communists are no different from anyone else; whether they lose an arm or a leg, they suffer as all of us do, and die as all of us die.

“And the Communist mother is the same as any other mother. When she receives the tragic news that her sons will not return, she weeps as other mothers weep. I do not have to be a Communist to know that. And at this moment Russian mothers are doing a lot of weeping and their sons a lot of dying.”

Chaplin continued suffering denigration and political harassment after the Second World War. His subsequent works criticizing the class inequalities, such as 1947’s Monsieur Verdoux, revived the accusations of Communism against him.

Even though he was never arrested during the Red Scare, he remained under strict surveillance from the FBI for almost 40 years. This reached its peak in 1952 when his entry permit was revoked by the US government, and the actor decided to spend his remaining years in Switzerland.

Read another story from us: Last US Casualty of WWI: Futile Gesture or Heroism?

It wasn’t until after Chaplin’s death when the true value of his service was actually realized. Chaplin was much more useful in the film studio than he would’ve been on the battlefield.

The laughter which his films produced was the much-needed cure for the sufferings of the war wounded soldiers – a cure which helped hundreds of thousands, if not millions, to stay alive and overcome the anxieties of their lives.