In 200 feet of water off the north coast of France, near the port of Cherbourg, lies a Confederate warship which never saw a Confederate port. CSS Alabama was commissioned by the South during the U.S. Civil War, built in Liverpool, armed in the Azores, and cruised against Union shipping around the world before finally being sunk near France.

The Alabama was a hybrid ship, powered by both coal and sail. She was built for speed in both modes, to hunt and capture Union commercial shipping while having the speed and flexibility to choose her battles against other ships-of-war.

In 1861 the Confederacy sent James Dunwoody Bulloch to England on a mission to procure two steam-sail hybrid vessels for the Confederate Navy. The Foreign Enlistment Act of 1819 forbade British shipyards from building or equipping warships for either side in the U.S. Civil war, but Bulloch got around that by having his two ships built without armaments, and equipping them later. The first, CSS Florida, would leave the Liverpool shipyards and sail to Nassau in the Bahamas to receive armament, equipment, crew, and commission.

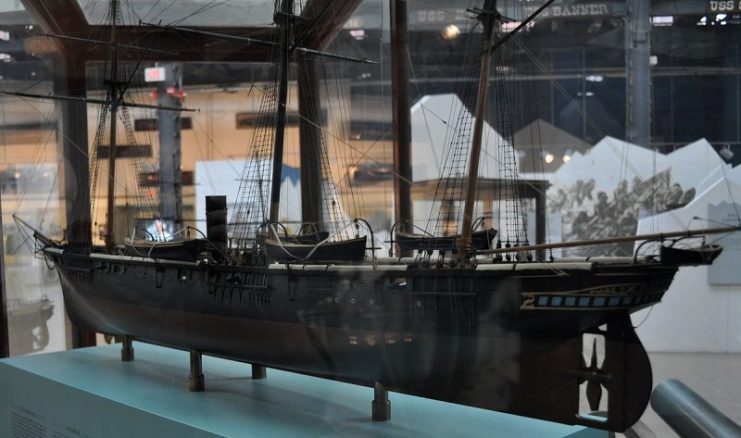

The second ship, known under construction merely as Number 290, would become the Alabama. She was a three-masted, barque-rigged ship, 220 feet long, and weighing 1100 tons. Her two boilers each produced 300 horsepower, both powering a single screw propeller which could be lifted out of the water when not in use. She carried 350 tons of coal, enough to operate the boilers for up to 20 days.

On July 29th, 1862, the ship, temporarily named Enrica, left Liverpool just ahead of a rumored seizure by British authorities. She sailed north around Ireland to avoid the USS Tuscarora, which had been assigned to watch her, and then on to the bay of Praya on the island of Terceira in the Azores, where she would be crewed and armed.

Her armaments also came from Britain, reaching the Azores aboard cargo vessels to work around the Foreign Enlistment Act. Six guns and most of her stores came aboard the Agrippina, which sailed from London as the Alabama was sailing from Liverpool. Aboard that ship were two pivot guns and four broadside guns.

Alabama’s most notable gun was a seven-inch, 100-pound Blakely-reinforced rifled gun, used for accuracy and power at long distances. Agrippina also brought her an 8-inch, 68-pound smoothbore pivot gun, and four six-inch, 32-pound broadside guns. Two more 32-pounders would fill out her armament when the Bahama arrived two weeks later carrying Alabama’s future captain, Raphael Semmes.

Semmes, born in Maryland in 1809, had been a lieutenant in the US Navy during the Mexican-American War, and then in peacetime practiced law in Mobile, Alabama. He was promoted to commander in 1855, but not given a ship.

After joining the Confederate Navy in 1861, he converted a small hybrid merchant vessel into the commerce raider CSS Sumter and set out to raid Union shipping, taking eighteen merchant vessels in six months before the ship became impractical to repair and was sold in Gibraltar. His success as a merchant raider led to his promotion to captain and assignment to the much larger Alabama to execute a similar mission.

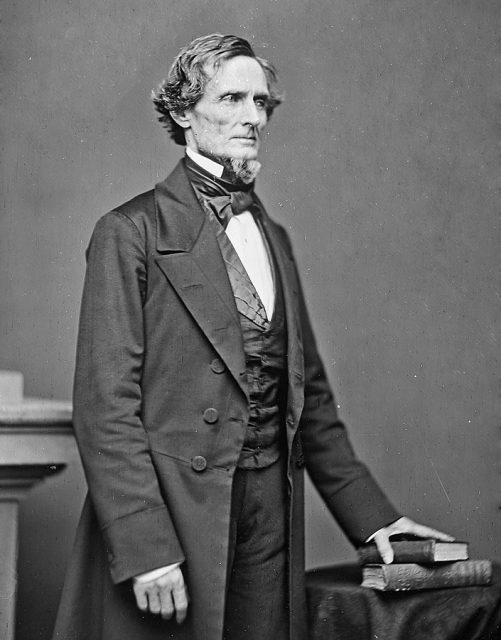

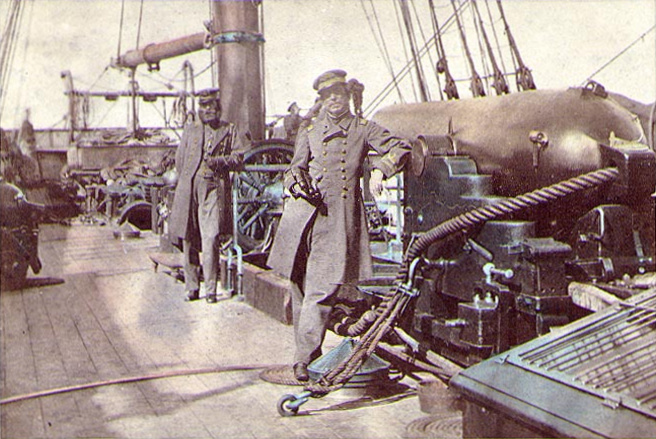

On August 24th, the ship made her way out of Praya and into international waters, where Semmes read his commission from Confederate President Jefferson Davis and renamed the ship the CSS Alabama.

With high wages, gold, and the promise of prize money, he convinced 83 sailors who had accompanied the three ships to sign on to the Confederate Navy and crew the new warship. Only Semmes and a few of his officers were actually from the South; most of the crew were British sailors willing to join for the promise of prize money.

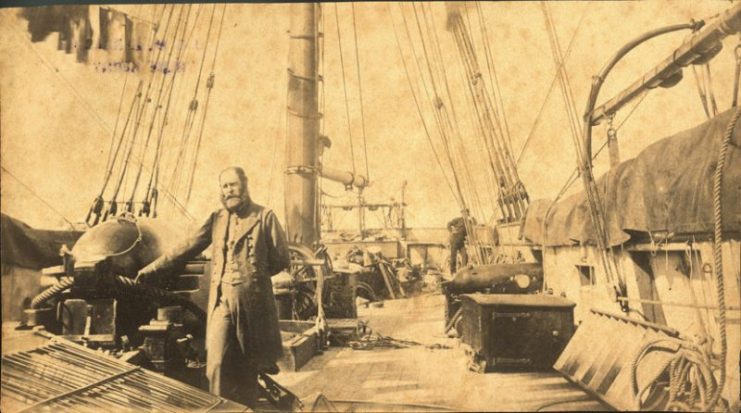

Now armed and crewed, Alabama sailed west for North American waters, where she spent months capturing and burning Union merchant ships, both in the waters off New England and in the West Indies. In January 1863 she sailed into the Gulf of Mexico, where she fought her first military engagement.

On New Year’s Day, Confederate troops had retaken the port city of Galveston, Texas, and Union warships were bombarding the city when Alabama arrived on January 11th. Semmes managed to draw the side-wheel gunboat USS Hatteras away from the rest of the fleet and sank her in an engagement which lasted only thirteen minutes.

However, the Union blockade of Galveston continued, and the Alabama had to withdraw. She sailed south and out of the Gulf to the coast of Brazil, which at the time was a popular destination for American shipping. This period was her most successful, as she took 29 prizes between February and July of 1863.

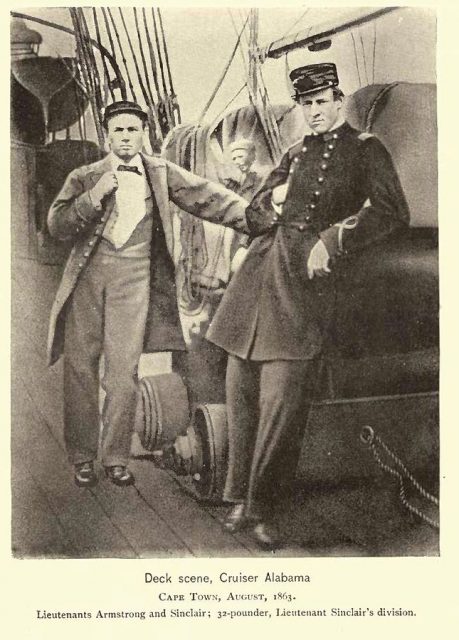

After Brazil, the Alabama crossed the Atlantic again, to raid subsequently around Cape Town, South Africa, in the Indian Ocean, and in the South Pacific. By the end of 1863, she had captured or burned 65 Union merchant ships, making her the most-successful commerce raider in history.

But after such a long voyage the ship was deeply in need of a refit, so Semmes sailed her to the neutral port of Cherbourg, where she arrived on June 11, 1864, and went into drydock for repair.

Three days later, the USS Kearsarge arrived and blockaded Alabama within the port.

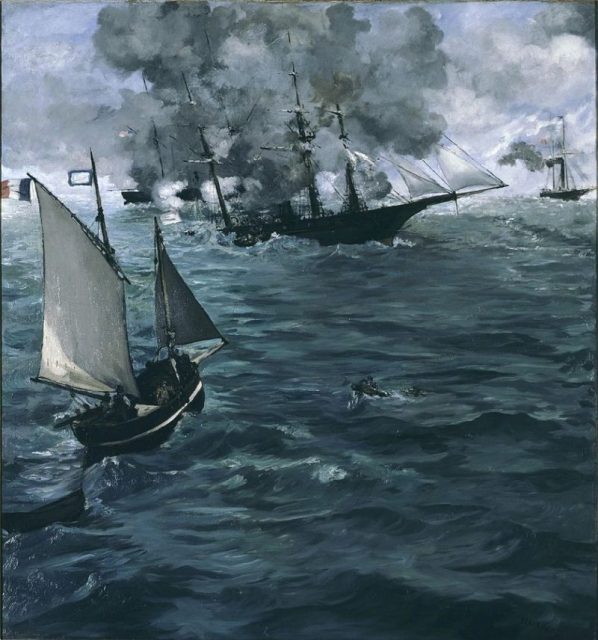

Though the Kearsarge was half-again as large as the Alabama, it featured two 11-inch guns the Confederate raider could not match, Semmes was unwilling to sit in port under blockade. He issued a challenge to Captain Winslow of the Kearsarge, and on June 19th sailed out of the harbor to meet her in battle.

Unfortunately for Semmes, Kearsarge’s superior gunnery, combined with his own ship’s poor state of repair, meant it was a short battle. After little more than an hour, having been hulled below the waterline by those 11-inch guns, Semmes struck Alabama’s colors and evacuated the sinking ship.

While most of Alabama’s crew were rescued and detained by the Kearsarge, Semmes and his officers were able to make their way to a private British yacht and escape Union custody. Semmes returned to the Confederacy, where he was promoted to rear admiral and commanded a squadron during the last days of the war.

After the war, Semmes served as a professor of moral philosophy and English literature at Louisiana State University, became editor of the Memphis Bulletin, and eventually resumed his legal career in Mobile.

In 1869, the United States demanded from Great Britain a payment for damages caused by the Alabama and other Confederate raiders produced in British shipyards. The issue was prominent in American efforts to expand into Canadian territory, but eventually, the two powers signed a treaty which committed them to settle the issue through international arbitration.

In 1872, a tribunal was held in Geneva with representatives from the U.S., Britain, Italy, Switzerland, and Brazil. The tribunal awarded the United States damages of $15.5 million for the activities of the Confederate raiders and is today seen as the founding event of international arbitration, and a key moment in the development of international law.

The wreck of the Alabama was discovered in 1984 by the French Navy mine hunter Circé. In 1989 a diplomatic agreement between the United States and France recognized the historical value of the wreck and paved the way for a partnership between nonprofit organizations in the two countries to salvage and preserve Alabama’s remains.

Subsequent diving missions have recovered several of the guns, as well as the ship’s bell and hundreds of minor artifacts. Many of these are now held at the U.S. Navy’s Naval History and Heritage Command in Washington, D.C.