In AMC’s drama TURN: Washington’s Spies, we follow Abraham Woodhull and company as they play a cunning game of deceit and trickery to gather intelligence for the Continental Army in the American War for Independence.

Basing his operation in his British-occupied hometown of Setauket, New York, Woodhull enlists the aid of local tavern keeper Anna Strong to ferry crucial intelligence to their friends in the Continental Army, Caleb Brewster and Benjamin Tallmadge, who in turn bring the intelligence to General George Washington himself.

Woodhull and Strong must accomplish this right underneath the noses of the British soldiers occupying their hometown, as well as Woodhull’s Loyalist father. Woodhull adopts the alias “Samuel Culper,” and begins his espionage, making trips to New York to scope out British military strength and eavesdrop on important conversations.

Interestingly enough, Woodhull, Strong, Brewster and Tallmadge existed in real life, as did almost all of the other main characters of the show. The Culper spy ring proved to be a vital part of General Washington’s intelligence network, keeping him informed of the British Army’s intentions and operations throughout the Colonies.

It is easy to see why AMC would choose such a spy ring as the subject of a television show. They did, however, take plenty of liberties with the historical facts, but on the whole, the show presents the major activities and accomplishments of the Culper Ring in a reasonably accurate manner.

Abraham Woodhull was born on October 7th 1750 in Setauket, New York, on Long Island. He was the son of Richard Woodhull, a wealthy judge, and Margaret Smith Woodhull, who did not die when Abraham was young as portrayed in the show, but in fact died in 1803, fifteen years after Richard.

The show also portrays Richard Woodhull as a devoted Tory, who grows ever suspicious of his son’s behavior, but in reality, he was more supportive of the Patriots, and circumstantial evidence supports this.

Abraham had in fact joined the county militia in 1775 with no apparent objection from his father, but became disenchanted and quit after two months.

In addition, Abraham’s cousin, Nathaniel Woodhull, a general in the Continental Army, had perished in the Battle of Long Island in 1776. It was believed that Nathaniel Woodhull had been captured and brutalized by the British, and died a miserable death.

Abraham was severely troubled by this, and there is no reason to assume his father did not feel likewise.

Abraham’s own family is also quite fictionalized in the show; he was unmarried during most of the war, and did not wed Mary Smith until 1781.

He also never had a son named Thomas; Mary would give birth to two daughters, Elizabeth and Mary, and a son named Jesse.

The show also portrays Richard Woodhull as a devoted Tory, who grows ever suspicious of his son’s behavior, but in reality, he was more supportive of the Patriots, and circumstantial evidence supports this. Abraham had in fact joined the county militia in 1775 with no apparent objection from his father, but became disenchanted and quit after two months.

In addition, Abraham’s cousin, Nathaniel Woodhull, a general in the Continental Army, had perished in the Battle of Long Island in 1776. It was believed that Nathaniel Woodhull had been captured and brutalized by the British, and died a miserable death.

Abraham was severely troubled by this, and there is no reason to assume his father did not feel likewise. Abraham’s own family is also quite fictionalized in the show; he was unmarried during most of the war, and did not wed Mary Smith until 1781.

He also never had a son named Thomas; Mary would give birth to two daughters, Elizabeth and Mary, and a son named Jesse.

In the summer of 1778, the need arose for a Rebel spy network in New York City, the site of the British Army’s continental headquarters. In June, the British had been forced to evacuate Philadelphia after the city became untenable due to vulnerability and stretched supply lines.

Adding to these problems was the threat of an attack on New York City by the Rebels and their new allies, the French. General Sir Henry Clinton, the commander of the British armies in Philadelphia, was ordered to leave the city and take his soldiers to New York to bolster defenses against a possible American and French attack.

The evacuating British were forced to make the trip to New York by land due to the threat of French naval attack, giving General Washington an opportunity to strike a crippling blow.

On 28 June, his Continental Army engaged Clinton’s army at Monmouth, but thanks to incompetence on the part of his second-in-command, General Charles Lee, Clinton was able to make it to New York with little more than a bloody nose.

Washington had enjoyed an effective spy network operating in Philadelphia, but with the British gone from there and New York crawling with redcoats, his focus now shifted towards starting an effective intelligence network around the British headquarters.

The task fell to his intelligence aide, Major Benjamin Tallmadge, to begin recruiting spies.

As depicted in the show, Abraham Woodhull was a cabbage farmer. In 1778, he was caught making his way into New York to sell some of his farm’s yield, and was jailed by the Rebels for “selling goods to the enemy.”

He faced a long sentence, but was freed unexpectedly by Major Tallmadge, a fellow Setauket native and childhood friend who had successfully managed to argue for his release.

In return, Tallmadge proposed to Woodhull that he start spying for the Continental Army; Woodhull agreed, and Tallmadge received approval from Washington.

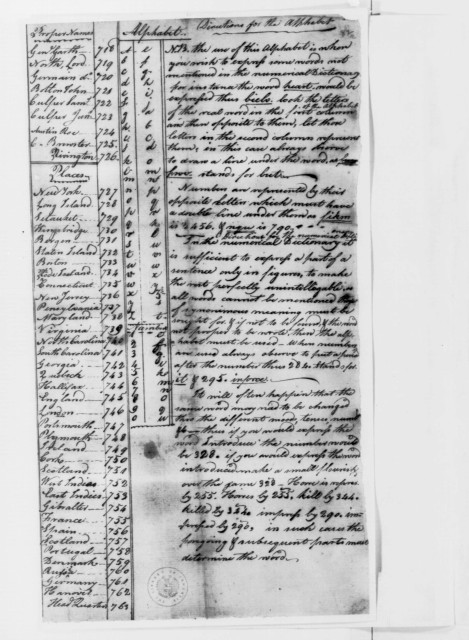

It was later decided by Tallmadge and Washington that Woodhull would be given the alias “Samuel Culper,” and the Culper spy ring was born.

Fueled by a strong desire to avenge his cousin’s allegedly brutal murder, Woodhull threw himself into his new job with a passion. In October 1778, he began making trips to New York every few weeks with the excuse that he was on “business” or visiting his sister.

He discovered that anyone traveling into the city was at exceptional risk of being detained and searched by British authorities, but that married couples almost always were not.

He thus enlisted the aid of Anna Strong, the wife of Selah Strong, a tavern keeper who was jailed aboard a British prison ship when the Culper Ring was formed.

The two often went to New York together masquerading as husband and wife, and the trick was effective, despite Strong being ten years older than Woodhull.

While in the city, he was able to observe naval strength, troop numbers, and glean potentially important information by eavesdropping on the conversations of British soldiers.

Woodhull would copy what information he could gather onto paper, and on his way back home to Setauket, he would hide the information in a prearranged location, a hidden cove on Long Island Sound.

The intelligence would then be retrieved by a certain boatman named Caleb Brewster, who was a lieutenant in the Continental Army. From Brewster, the intelligence would be passed on to Major Tallmadge, then to General Washington’s desk.

Woodhull turned out to be a very effective spy, and his reports were uncannily accurate. General Washington had often been frustrated by the exaggerated figures that he had received from spies in the past, and expected more of the same from Woodhull.

His fears were eased when Woodhull sent him a report in November 1778 that provided almost exact figures of British troop strength in New York.

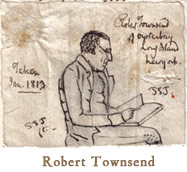

Washington was impressed: “His account has the appearance of a very distinct and good one and makes me desirous of a continuance of his correspondence,” he wrote. Woodhull also recruited other spies into the ring; one such spy was Robert Townsend, who worked in a New York boardinghouse which was frequented by British soldiers.

Aliased “Samuel Culper, Jr.,” Townsend gave Woodhull a reliable source within the city itself, and made his job much easier. The job was not without its risks, though, and Woodhull cut it close on many occasions.

In one incident, a Tory privateer named John Wolsey reported a rumor that Woodhull was spying for the Continental Army.

The rumor fell upon the ears of a certain Queen’s Rangers captain by the name of John Graves Simcoe.

Captain Simcoe, a gruff and raucous character, had taken over the same outfit of Rangers once commanded by legendary tracker Robert Rogers.

Upon hearing of Woodhull’s rumored espionage, Simcoe marched his Rangers into Setauket and proceeded to raid the Woodhull household.

Abraham, however, was nowhere to be found- he had left for New York the previous day. His father, Richard, was unharmed, but Simcoe had plundered the house “in the most shocking manner” in order to obtain “compensation” for his troubles.

When Abraham returned, it took the help of a friend of the Woodhulls, a general’s adjutant, to assure Simcoe that Abraham was a proper Loyalist.

Despite his success, the espionage business wore Woodhull out physically as well as mentally. Over time, he began to fear for his safety, and Benjamin Tallmadge’s reports to Washington reflect Woodhull’s growing timidity.

A number of close calls with British authorities had made both Woodhull and Robert Townsend jumpy. Townsend, in fact, had somewhat foolishly recruited his cousin James into the ring, who ended up being arrested by the Continental Army for allegedly being a British spy!

The incident struck fear into Townsend’s heart, as it demonstrated just how easy it was to be captured. Townsend then decided he was through with espionage.

Woodhull was unable to talk him out of it, and it took a meeting with Benjamin Tallmadge to convince him to continue spying, with the provision that he would only deliver information to Woodhull verbally.

Sensing the volatile mental state of both his top operatives, General Washington decided to halt the operations of the Culper Ring. Not two months had passed, however, when Washington needed their services again.

A French fleet was sailing into Rhode Island to attack British forces there, and Washington wanted information that could make the job of the French easier. Washington sent Caleb Brewster out to Setauket to notify Woodhull of the situation.

Since Woodhull was ill at the time, another spy named Austin Roe was sent to New York to get information from Robert Townsend, who sent a report back to Woodhull for forwarding to Washington.

Woodhull prefaced the information with the admonishment that the intelligence contained “news of the greatest consequence perhaps that ever happened to your country.”

The British had been aware of the planned French attack for over a month, thanks to the treason of the infamous General Benedict Arnold himself. The British knew the exact strength of the French fleet, and were going to wait for them to make harbor and ambush them.

The intelligence provided by the Culper Ring prevented what might have been a terrible disaster, and was one of its most important triumphs.

The Culper Ring had not seen the last of Benedict Arnold, though. Arnold had defected to the British side after he became increasingly ticked off at the Patriots for not properly recognizing his achievements on the battlefield.

He began providing information to the British in 1779, and started a correspondence with Major John Andre, the head of British intelligence. One of the facts he provided was that a spy ring was operating on Long Island, and before long suspected spies were being arrested throughout the area.

Thankfully, no actual spies were arrested, and the Ring was able to continue its work, although Woodhull and Townsend were again understandably anxious. In 1781, Woodhull resigned from his duties.

He had recently married Mary Smith, and was afraid of putting his family at undue risk. Nevertheless, he continued to send letters to Washington, informing of anything of importance he came across.

The war finally ended in 1783, with the Continental Army victorious thanks to assistance from the French. Woodhull immediately set to work attempting to collect the money due him for his services.

Washington was annoyed; Woodhull had always made a fuss about payment during the war, but Washington saw fit to reward him for his invaluable service. As the British departed the colonies, a celebration was thrown in Setauket.

Among the attendees were the Woodhull, Tallmadge and Strong families, along with Caleb Brewster and Austin Roe’s family. Benjamin Tallmadge, Setauket’s highest-ranking military officer, was appointed the “master of ceremonies.”

Abraham Woodhull followed his father’s footsteps and became a magistrate, and was appointed “First Judge of Suffolk County” in 1799. He hardly ever spoke of his work as a spy.

Two of his children, Elizabeth and Jesse, married into the Brewster family. His wife Mary died in 1806, and in 1824, he remarried. He died two years later, on 23 January 1826. Selah and Anna Strong lived out the rest of their lives quietly in Setauket.

Benjamin Tallmadge became a wealthy investor, and in 1801 was elected to Congress. Devoutly religious, he founded a missionary school in 1817, and was known to be sharply critical of the institution of slavery. He died in 1835.

Caleb Brewster joined what is today the Coast Guard in 1793, retired in 1816, and died in 1827. Robert Townsend went into business with his brother Solomon, but the business failed, and Townsend never got back on his feet. He died a lonely man in 1838.

The TV show TURN took plenty of historical liberties; for instance, there is no evidence of a love affair between Abraham Woodhull and Anna Strong.

Major Edmund Hewlett was in fact named Richard Hewlett, and he was actually married during the entirety of the war, and he and his wife had eleven children; there is no evidence of a relationship between him and Anna Strong either.

Despite its inaccuracies, TURN: Washington’s Spies is an entertaining yet fitting tribute to the brave operatives of the Culper Ring, and shows just how dangerous and critically important their jobs were.

Sources:

“The Battle of Monmouth 1778.” Britishbattles.com, accessed 15 May 2016. http://www.britishbattles.com/battle-monmouth.htm

Braisted, Todd W. “Lieutenant Colonel Richard Hewlett: The Loyal-est Loyalist.” TURN to a Historian, 27 April 2015. Accessed 18 May 2016. https://spycurious.wordpress.com/2015/04/27/lieutenant-colonel-richard-hewlett-the-loyal-est-loyalist/

“Long Island Surnames: Abraham Woodhull.” Longislandsurnames.com, accessed 15 May 2016. http://www.longislandsurnames.com/getperson.php?personID=I0519&tree=Woodhull

Markle, Donald E. The Fox and the Hound: The Birth of American Spying. Fall River Press, 2014

Rose, Alexander. Washington’s Spies: The Story of America’s First Spy Ring. Bantam, 2014.

Schellhammer, Michael. “Abraham Woodhull: The Spy Named Samuel Culper.” Journal of the American Revolution, 19 May 2014. Accessed 18 May 2016. https://allthingsliberty.com/2014/05/abraham-woodhull-the-spy-named-samuel-culper/