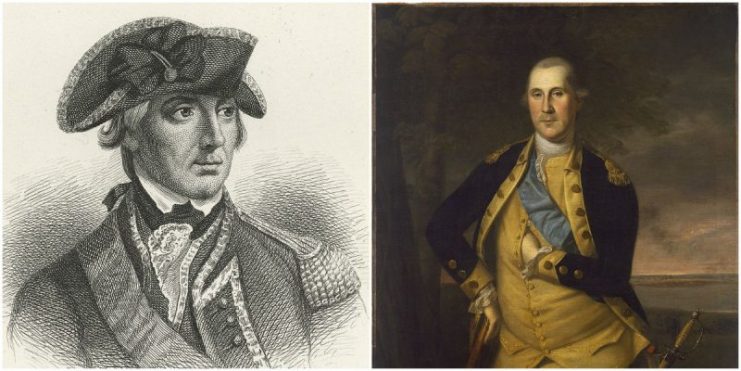

The Battle of Long Island took place in Kings County, New York on August 27, 1776 as part of the New York and New Jersey Campaign of the American Revolutionary War. It went on to become the largest battle of the campaign with the British Army under the command of General William Howe securing a victory over the American Continental Army led by General George Washington.

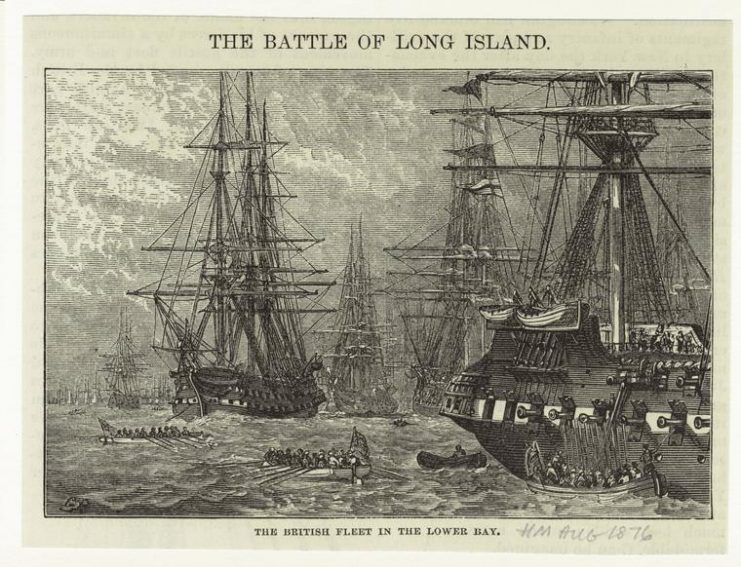

Aware of the strategic importance of New York City and that the Harbour of Manhattan Island would provide the British Navy with an enormous advantage if they should take it, Washington moved his army to Manhattan to prepare his defences, expecting the British to strike there first.

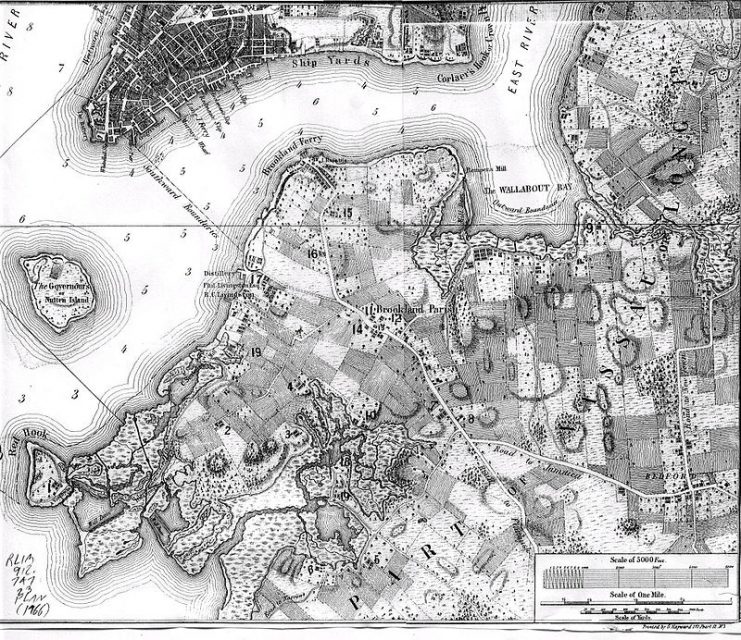

Howe’s arrival at Staten Island was unexpected but did not go undetected and while he awaited reinforcements, Washington set about erecting fortifications along the East River Shoreline in Long Island.

The Patriots’ civil engineer in charge, newly promoted Major General Nathaniel Greene was tasked with the construction of fortifications and digging of trenches for the Army.

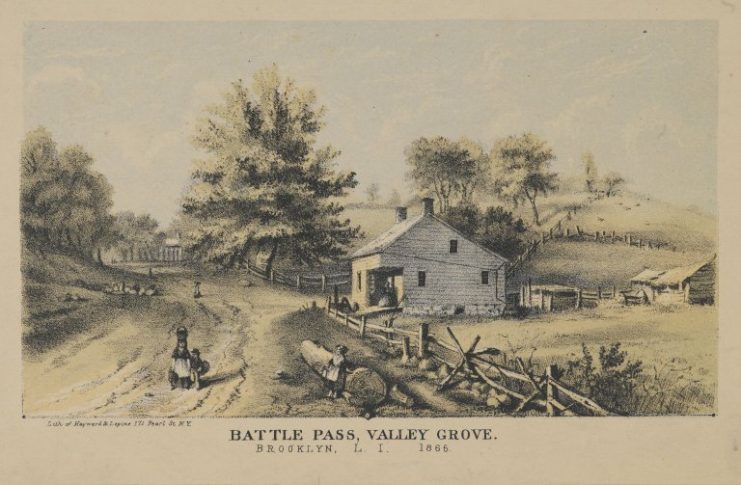

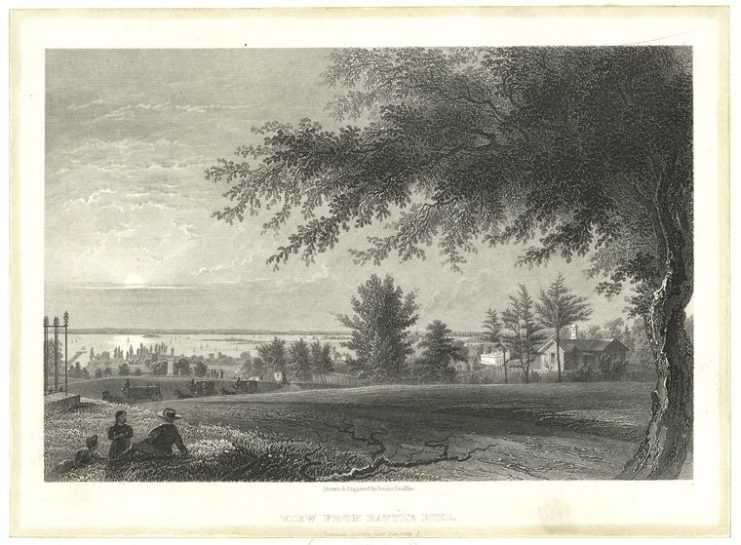

He chose to build the line of redoubts around Brooklyn Heights which were reinforced by some felled trees. These barricades ensured a vantage position of defense prepared to withstand any assault from the British Army.

The Continental Army was thereafter reinforced by another 9,000 troops, making a total of 20,000 Patriots under Washington’s command. The commander in chief expected no less than a heavy battle for New York and was hell bent on defending the city even though the odds were not in his favor.

Having built the fortifications, Washington sent 4,000 of his troops to defend it under the express command of Greene. Greene however was not able to partake in the battle as he became severely ill and he was subsequently replaced by General John Sullivan of New Hampshire. Sullivan was later relieved of general command and senior General Israel Putnam was placed in charge.

Sullivan and Major General William Alexander, otherwise known as Lord Stirling were given command Guan Heights which were in front of the Brooklyn Heights and controlled its major route.

Sullivan was to defend the roads leading from Flatbush and Bedford into Brooklyn with a force of two thousand men, while six thousand soldiers remained at Brooklyn Heights under Putnam’s command.

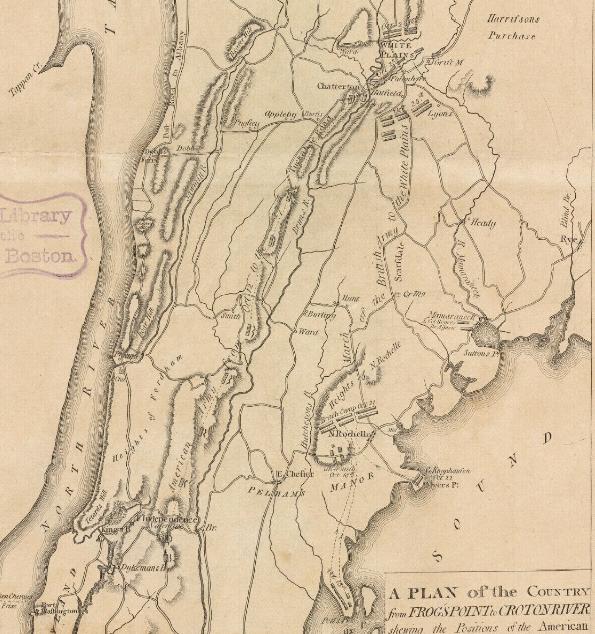

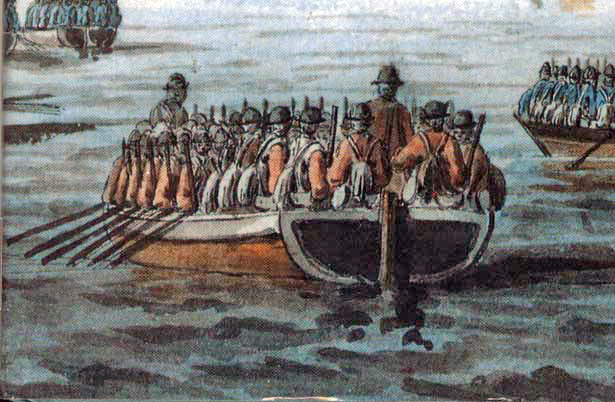

A small force of 4,000 men left Staten Island under the command of British Generals Henry Clinton and Charles Cornwallis. They were later joined by another 12,000 troops around noon who landed on Long Island soil. Awaiting further instructions, Cornwallis advanced his troops and lay in wait just outside Flatbush, Brooklyn.

Washington was immediately alerted of the recent developments in the area, but was told that only a small portion of the British force had advanced there. Fearing it to be a diversion, he sent another 1,500 soldiers as reinforcements to Brooklyn Heights.

The British troops were reinforced yet again by another 5,000 Hessian troops, placing the army at 20,000. Clinton outsmarted the patriots by taking the Jamaican Pass; a less guarded route through the heights. The five patriots stationed there mistook the British who arrived there at 9:30 PM to be American soldiers and were captured without firing a single shot.

The British were playing the Continental Army quite well, they left their campfires at Flatbush burning leading the unsuspecting patriots to believe that they were still camped.

Meanwhile 4,000 British and Hessian troops under the command of General James Grant awaited signal from Clinton’s division to attack the Americans at the front. In the morning of the next day, two cannons were fired and an assault began against Sullivan’s troops at the Flatbush and Bedford roads.

The Hessians attacked fiercely against the patriots killing everyone in their path as they charged through the front lines.

Realizing his erroneous decision to send only a few troops to Long Island, Washington rushed out of Manhattan to Brooklyn, there was hardly anything he could do now. The British had prepared a well calculated assault against his defences and were pushing the patriots far back into the city. Clinton’s forces flanking the Continental Army with Grant enforcing a frontal assault.

Stirling soon pulled his armies backwards toward the Gowanus Creek after withstanding a direct assault from Grant for four hours. The creek was the only plausible escape route for Stirling’s men as Hessians and British troops charged at them from the left and rear positions.

Leaving behind the brave Maryland 400 under the command of Major Mordecai Gist, Stirling’s troops scampered across the 80 yard creek to safety. The small army under Gist’s command led two attacks against the British, buying time for others to retreat safely.

Then the retreated themselves after launching the last attack on the Vechte-Cortelyou House. The Maryland troops suffered two hundred and fifty six casualties with only a handful of them making it over the creek.

After conceding the crushing defeat at Long Island, Washington gathered the troops and ordered a retreat toward Manhattan. With the deaths of over two thousand troops, Washington and all America were devastated by the battle.

More Images –