During the Second World War, the British broke from their famous gentlemanly conduct. Sabotage, prison break, assassination – no dirty trick was beyond the remit of their newly founded covert operations teams.

These are a few of the men behind those operations.

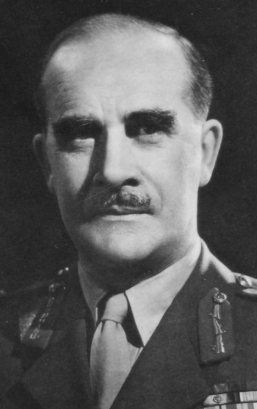

Colin Gubbins

Smartly dressed and armed with a sharp sense of humor, Gubbins was the head of most of Britain’s covert operations.

A veteran of the First World War, he had subsequently fought against the Bolsheviks in Russia and Sinn Fein in Ireland. He also spent a tour of duty in India and wound up in military intelligence.

Seconded to the newly formed Special Operations Executive, Gubbins turned his vast experience to overseeing the training of special agents and the planning and execution of their covert operations. Most of Britain’s covert operations of the war were run through Gubbins’s teams.

William Fairbairn

William Fairbairn was an unlikely-looking killer. Portly, bespectacled, and stooped, some people nicknamed him “The Deacon” because of his resemblance to a Church of England priest. But his other nickname, “Shanghai Buster,” reflected the violence of his past.

A former Royal Marine, Fairbairn had learned martial arts from the Japanese while stationed in Korea. He then spent 33 years working for the Shanghai Municipal Police, leading his Riot Squad against the city’s infamous criminal gangs.

When Fairbairn turned up unannounced at the War Office, offering his services to the British military, he was already 58 years old. But having studied martial arts from all over the world, he was a deadly close-range killer.

Eric Sykes

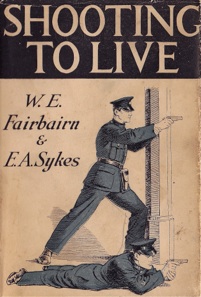

Fairbairn brought with him one of his Riot Squad veterans, Eric Sykes. Softly spoken and bearing a benevolent smile, Sykes looked as little like a killer as Fairbairn did. But he was an expert in pistol shooting. He had worked as a representative of the Colt and Remington companies.

Sykes and Fairbairn had written the book on dirty combat. Several books, in fact, including Shooting to Live and All-in Fighting. But there was no place for men with their skills in the conventional British Army.

Instead, they were recruited by Gubbins. They became the prime instructors at a training school in the Scottish Highlands, where they taught Allied commandoes and covert operatives how to kill with a pistol, a knife, or bare hands.

Gus March-Phillips

Gustavus Henry March-Phillipps was recruited by Gubbins in 1940 to join his covert teams. A veteran of the dirty warfare on the North-West Frontier of India and a survivor of the Dunkirk disaster, March-Phillipps was one of Britain’s toughest soldiers.

Smart, bold, and willing to break the rules when needed, March-Phillips led one of the most daring expeditions of the war: stealing three Axis ships from a neutral port in West Africa. He covered his tracks so well that no-one could prove it had been British work.

Millis Jefferis

A grizzled, chain-smoking officer with a leathery face, Jefferis had begun his military career as an engineer on the North-West Frontier.

An expert in building bridges and viaducts, he also gained experience in guerrilla warfare through the Waziristan campaign of 1922, for which he was awarded the Military Cross.

During the Second World War, Jefferis ran a special unit within the Ministry of Supply. They specialized in developing and producing weapons for Gubbins and his teams, especially explosive devices custom designed for specific purposes such as sinking ships and destroying power plants.

Stuart Macrae

An engineer turned journalist, Macrae’s life was transformed by a single meeting in the spring of 1939.

Millis Jefferis had seen an article about powerful magnets in Armchair Science, a magazine Macrae edited. Jefferis needed to develop an underwater mine with a powerful magnet and a reliable time-delay detonator but couldn’t find a magnet powerful enough, so he approached the journalist.

Macrae had some armaments experience, having designed mob-dropping devices for low-flying planes. After an alcohol-fueled lunch, he accepted the challenge of creating the mine.

It was a decision that would lead Macrae to work full-time for Jefferis, producing specialist armaments for Allied commando missions. But not before he had recruited his main collaborator in this work…

Cecil “Nobby” Clarke

The founder of a small company manufacturing caravans, Clarke was the company’s principal designer and the man behind its unique suspension system. He loved to create new devices in his quest to build better caravans.

Macrae had met Clarke in 1937 after the caravan designer submitted an advert for an unusual vehicle to a magazine Macrae was editing. Two years later, struggling with the design of Jefferis’s mine, Macrae went to visit him again.

Together, the two of them designed the mine, testing it out at the local swimming baths. Thanks to their successes during testing, they were employed to produce the mine. Soon, both were working for Jefferis, designing his specialist weapons.

George Rheam

An industrial engineer who had worked at Metropolitan Vickers and the North Metropolitan Power Company, Rheam was one of the country’s leading experts in electrical generators.

As war approached, he realized that almost any generator could be crippled with only a small amount of explosives. It was this sort of thinking that led him to work for Jefferis.

Read another story from us: Lions Roar: 5 British Self-Propelled Guns of WWII

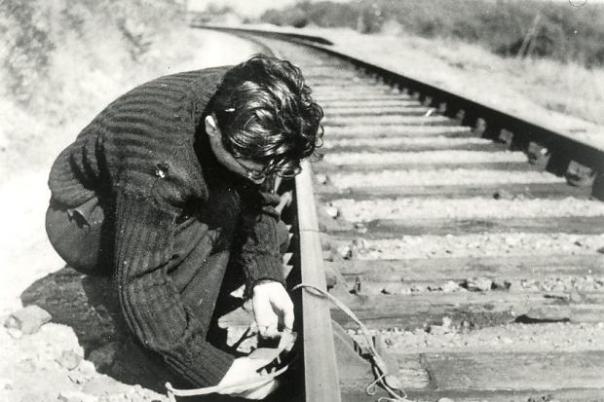

Rheam specialized in developing explosive charges and operational plans to destroy enemy machinery such as power stations and trains. He would send trainees on mock sabotage expeditions into real British power plants, without warning the owners and guards, to ensure that the men had real hands-on experience.

After the war, he wrote a secret report detailing the critical role of sabotage in the Allied victory, with an eye to its place in the future of warfare.