On March 7, 1960, the American aircraft carrier Kearsarge saved Soviet soldiers who had drifted in the ocean for 49 days without food or water. This incident became world famous and eclipsed most of the political news of the time.

In January 1960, the self-propelled barge T-36 filled the role of a floating transshipment point near the island of Iturup on the South Kurile ridge. This vessel operated at a maximum speed of 9 knots per hour, and would sail up to nearly 1,000 feet away from the coast in order to deliver ammunition and food to large ships that could not approach the island’s rocky shore.

On the night of January 17, 1960, a hurricane arose, which broke T-36‘s anchorage and carried the barge out to sea. The crew had been neither warned about the approaching storm nor provided with the requisite 10-day rations. There were four soldiers aboard: junior sergeant Askhat Ziganshin, and rank and file Philip Poplavsky, Anatoly Kryuchkovsky and Ivan Fedotov.

Within 10 hours, the T-36 crew made three attempts to return to the island. The waves reached a height of about 49 feet. All attempts to return were unsuccessful. In addition, the barge received extensive damage and lost its radio. The last message from T-36 was “We [anticipate] disaster, we cannot come ashore.”

Soon the barge ran out of fuel. At about 10 PM, she was in the open ocean. When the hurricane winds quieted, the search for the missing barge began. On the shore, pieces from T-36 were found, which led searchers to believe that the barge had sunk. The relatives of the missing soldiers were notified of their deaths.

One story claims that the search for T-36 was stopped due to the prohibition of ships entering that part of the sea because tests of secret missiles were conducted there. However, several facts prove this version is not completely true.

Adrift in the ocean

With each hour, T-36 drifted farther and farther away from the Kuril Islands to the southeast. After some time, the barge was in the warm current of Kuroshio, which Japanese anglers called the “Black Current.” Due to the high speed of ocean currents–up to 78 miles per day–there are practically no fish in this area.

Askhat Ziganshin recalled, “We did not catch a single fish, although we tried to do it all the time, we prepared the gear from the improvised material that we found on board. Then we learned that there was no living creature in those places because of the powerful ocean current.”

In addition, T-36 was now in the zone where Soviet missile testing was planned. As a result, there were no other ships present other than an occasional warship, so the chances of being noticed were reduced nearly to zero.

On the second day, the crew collected all the provisions that remained in the barge. The reserves were 15-16 spoonfuls of cereals, a loaf of bread, one can of food, and some potatoes, which turned out to be tainted with diesel fuel. Freshwater was available only in the engines’ cooling systems, but it was of poor quality–muddy and rusty. When the water in the cooling systems was gone, the soldiers collected rainwater.

Despite the fact that they initially planned to eat only once every two days, all the food products quickly gone. Each of the crewmembers lost at least 66 pounds before they were rescued. In order to “deceive the stomach” in the meantime, Askhat Ziganshin devised ways to eat almost inedible things such as leather belts, tarpaulin boots, soap, and toothpaste. Ziganshin explained:

“We cut [the leather belt] finely, into noodles, and began to boil “soup” out of it. Then we [ate] the strap from the walkie-talkie. We began to look for what else we have leather. Found several pairs of tarpaulin boots. But they are not so easy to eat, too hard. We brewed them in the ocean water to get rid of the shoe polish, then cut into pieces, thrown into the fire, where they turned into something like charcoal, and it was eaten.”

Because of the cold, the crew of T-36 was forced to sleep on one bed, warming each other. Despite being famished, they never broke discipline.

On February 23, the crewmembers wanted to celebrate “Defender of the Fatherland Day,” which is a national Russian holiday. However, according to their schedule of meals, they could not eat that day. Then Ziganshinin suggested they smoke the last cigarette as their celebration of the day.

Unexpected Rescue

On March 7, 1960, on the 49th day of its uncontrolled drift, the barge was noticed by the American aircraft carrier Kearsarge, which was transiting from Japan to California.

Ziganshin recalled, “We lay exhausted in the cockpit. I heard a noise and went out to look. It turned out that there was a helicopter over us. We still did not understand who it was but tried to explain that we needed food, fuel, and a map. We could go on our own.”

Two times, American helicopters offered help, but the Soviet soldiers feared that they could be considered traitors in their homeland for accepting it. But when the American aircraft carrier began to depart, that greatly frightened the Soviets, so that when the ship returned the next day, they decided to go aboard.

On board the aircraft carrier, the Soviets were offered food. The Americans were surprised that the hungry men maintained self-control and ate very little–they sensed they could die if they ate too much after starving. Ziganshin lost consciousness while washing up, and did not wake again for 3 days.

He said, “In the first days after the rescue, I seriously thought about suicide, looked out the window, I wanted to throw myself away. Or hang [myself] on the pipe.”

The rescued Soviets were taken to San Francisco, where they received civilian suits, held a press conference, and gave multiple interviews. The mayor of San Francisco gave them a symbolic key to the city. Each man was also given $100, which they spent on excursions.

All those rescued were offered political asylum, but they refused. Later, they were taken to New York, where they spent time with representatives of the Soviet embassy. A special telegram from Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev was delivered to them, an excerpt of which said “I wish you, dear compatriots, good health and an early return to the homeland.”

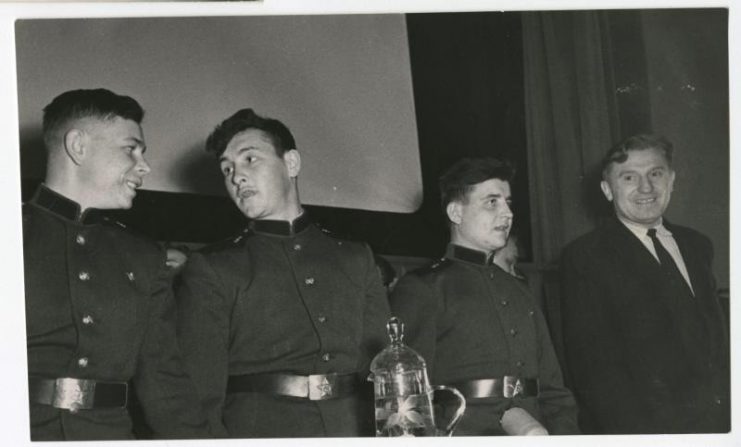

From New York, the rescued men sailed to Europe on the ship Queen Mary, and from Europe, now back in military uniform, they proceeded to Moscow.

In the Soviet Union, they gained the universal glory of heroes and attended a reception in which Nikita Khrushchev and Defense Minister Rodion Malinovsky personally greeted them. Each of the men received the Order of the Red Banner and presents.

The soldiers were invited to appear on many radio and TV programs. In addition, a film entitled “49 Days” was based on their story. Ziganshin later said that he did not regret the incident, and that it had greatly changed his life.