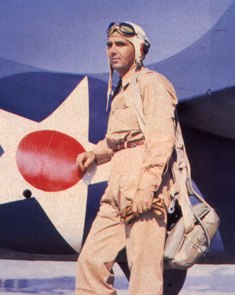

U.S. Navy Lieutenant Edward “Butch” O’Hare holds the distinction of being the first Naval Aviator to be awarded the Medal of Honor—the United States’ highest military honor—during World War II. His accomplishments as a fighter pilot are incredible in their own right. However, there are a plethora of story lines regarding this modest, unassuming young hero.

Have you ever read between the lines of a Medal of Honor citation, and wondered just what the recipient was like, and what other details surrounded the heroic action described in the award citation?

The President of the United States in the name of The Congress takes pleasure in presenting the Medal of Honor to O’HARE, EDWARD HENRY

Who exactly was Lieutenant O’Hare?

Rank and Organization: Lieutenant, U.S. Navy. Born: 13 March 1914, St. Louis, Mo. Entered Service at: St. Louis, Mo.

Behind these dry facts figuratively stands a man who was a human like anyone else, though perhaps with a more unique childhood than others. He was the son of Edward “Easy Eddie,” J. O’Hare, a successful lawyer and dog track operator who dabbled in flying airplanes on the side—and who familiarized his teenage son, nicknamed “Butch,” with flying as well.

Unfortunately, as the notorious Al Capone’s former lawyer and business associate turned government witness, Easy Eddie was murdered by unidentified gunmen in 1939.

The younger O’Hare took a much different path in life. He graduated from the United States Naval Academy in 1937, served for two years on the battleship USS New Mexico, and completed Navy flight training in Pensacola, Florida in May 1940. Officially a Naval Aviator, Ensign O’Hare was ordered to Fighter Squadron Three (VF-3) aboard USS Saratoga, which was based in San Diego, California.

The next twenty months were eventful for Butch. During that time, VF-3 bounced from Saratoga, to USS Enterprise, back to Saratoga, and finally was reassigned to USS Lexington after the United States entered World War II and Saratoga was damaged by a Japanese torpedo. Butch, meanwhile, made a name for himself as a gifted aviator and marksman, and by January 1942 he had received a temporary promotion to Lieutenant.

His commanding officer, John Thach, said of him,

“He had a sense of timing and relative motion that he may have been born with, but also he had that competitive spirit. When he got into any kind of a fight like this, he didn’t want to lose….When he first got to the squadron he studied all the documents that we had on aerial combat, and he just picked it up much faster than anyone else I’ve ever seen. He got the most out of his airplane.”

Other Navy awards: Navy Cross, Distinguished Flying Cross with 1 gold star.

Butch received these three awards after his Medal of Honor: the Distinguished Flying Crosses in August and October 1943, and the Navy Cross posthumously, because in the face of an imminent Japanese attack on Lexington’s task group near Tarawa, Butch “personally organized and voluntarily led the first night fighter section of aircraft to operate from a carrier, at night, against enemy aircraft, although he well knew the hazard involved.”

Hazardous indeed, for Butch never returned from that night mission in November 1943.

Citation:

For conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in aerial combat, at grave risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty, as section leader and pilot of Fighting Squadron 3 on 20 February 1942. Having lost the assistance of his teammates,

According to John Thach, Lexington only launched a handful of planes, including his own, when the first formation of enemy bombers approached. Thach ordered Butch and his wingman, along with some others, to stay near Lexington as combat air patrol, while Thach’s group went to investigate where the Japanese planes had come from and hopefully intercept any others.

Obviously, they missed the second wave of incoming bombers. Of the pilots left behind, all but Butch and his wingman were too far away to intercept the Japanese before they would get within bombing distance of Lexington.

Lt. O’Hare interposed his plane between his ship and an advancing enemy formation of 9 attacking twin-engine heavy bombers.

The Japanese planes were Mitsubishi G4M Navy Type 1 Attack Bombers, code-named “Betty” by the Allies, and were actually medium bombers. They were land-based, long-range aircraft that could carry over 2,000 pounds of bombs each. Nine of them were bad news for Lexington.

Without hesitation, alone and unaided, he repeatedly attacked this enemy formation, at close range in the face of intense combined machinegun and cannon fire.

Butch and his wingman were the only ones close enough to try to stop the Japanese in time—but the wingman’s machine guns all jammed at that crucial moment. Butch’s Grumman F4F-3 Wildcat fighter was now the sole aircraft “in the right place, at the right time” that was able to immediately defend the carrier.

Butch had four .50 caliber Browning machine guns with which to shoot at the approaching bombers, but as the sole occupant of his plane, he had to fly and shoot. The Bettys, by contrast, were manned by a crew of seven men, and were each armed with three 7.7mm machine guns as well as a 20mm “cannon”, all operated manually by separate gunners. Four guns against thirty-six: talk about overwhelming odds!

Despite this concentrated opposition, Lt. O’Hare, by his gallant and courageous action, his extremely skillful marksmanship in making the most of every shot of his limited amount of ammunition, shot down 5 enemy bombers and severely damaged a sixth before they reached the bomb release point.

The Browning AN/M2 machine guns in Butch’s Wildcat were capable of holding 450 rounds each, enough for only 30-40 seconds of continuous fire, and he had nine targets! His marksmanship skills served him well as he shot down five bombers so quickly and effectively that eyewitnesses reported watching three of them fall simultaneously. The remaining bombers failed to land any hits on the carrier.

As a result of his gallant action—one of the most daring, if not the most daring, single action in the history of combat aviation—he undoubtedly saved his carrier from serious damage.

There is little doubt that Butch O’Hare’s heroic actions ensured that Lexington lived to fight another day, but what he did would also have a larger and more significant impact on the nation as a whole.

Twenty-one years later, while giving a speech to re-dedicate the naming of Chicago’s O’Hare International Airport in Butch’s honor, President John F. Kennedy summarized that impact:

“I remember as a young naval officer myself how the extraordinary feat of “Butch” O’Hare captured the imagination not only of our Armed Forces but also of the country.

His extraordinary act in protecting his ship…while he was alone, shooting down five of the enemy, during difficult days in the Second War, gave this country hope and confidence not only in the quality and caliber of our fighting men, but also in the certainty of victory.”