Admittedly sometimes you have to push technology in order to achieve something really special. But one cannot help wondering if the military tries far too hard to be clever and often ends up failing badly.

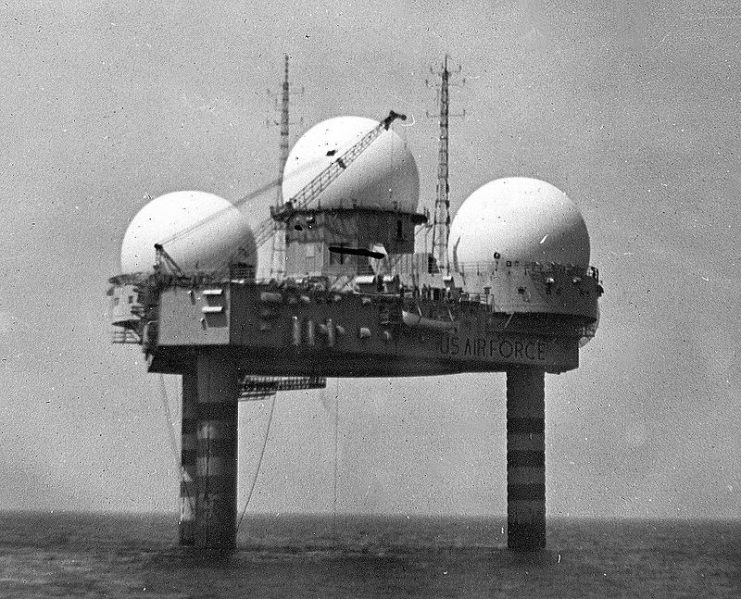

- SAGE (Semi-Automatic Ground Environment) Coordinated Integrated Radar Network

American: 1958 to 1983

The idea of an integrated air defense network was a good one — in theory, at least. Data could be linked and gathered from a vast network of radars across the United States so that a pilot could guide his fighter aircraft quickly and efficiently to intercept enemy bombers.

So, the Americans came up with SAGE (Semi-Automatic Ground Environment). The idea was that aircraft of the ADC (Aerospace Defence Command) would be guided and controlled by the system.

It was hoped the system would coordinate a controlled interception in real time while also assessing the overall tactical situation and reacting accordingly. SAGE would also coordinate long-range surface-to-air missiles.

However, the main problem was that it was developed in the 1950s when radar was still a relatively new technology and computers were very much in their infancy.

To illustrate the true scale of the programme, both the number of personnel involved (both military and civilian) and the funding mad available exceeded the Manhattan project. It cost billions of dollars.

SAGE had 23 vast control centers scattered across the United States, including one in Canada. Each housed a 250-ton computer called an AN/FSQ-7, which was the biggest computer ever built.

However, the system was forever plagued with technological and reliability issues. Despite numerous upgrades, it was, at best, barely adequate. But it did work and was, without doubt, an amazing endeavor.

The system was phased out in the 1980s, being replaced with more versatile airborne early warning and control system (AWACS) aircraft. This system worked in tandem with ground stations equipped with more powerful computers with microprocessors coupled to a whole new generation of radars.

To be fair, though the SAGE system had been costly and hard to maintain, its basic principles of coordination and management in defense of an airspace laid down the foundations of America’s modern defense network.

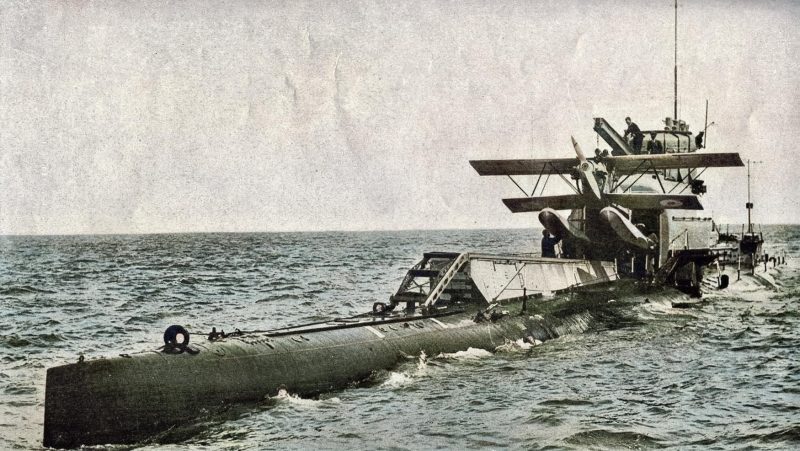

- Submarine Aircraft Carriers.

Various Nations: Late 1920’s to 1945.

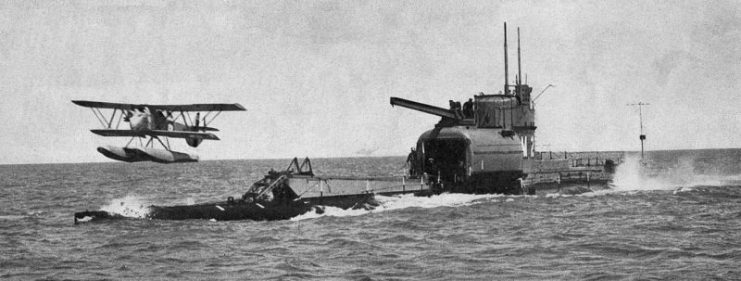

Many of the entries on this list were good ideas that were overly-complicated and ultimately ended up being replaced by simpler, better ideas. But the submarine aircraft carrier concept so beloved by the French and Japanese in the 1930s and 40s was flawed from start to finish.

The idea was that the aircraft carrier submarine would surface near the enemy target and launch an unanticipated aerial attack. Then, once the mission was complete, the host submarine would retrieve the bombers, submerge, and sneak away undetected.

The reality was that virtually all these carriers could only transport an aircraft with a strictly reconnaissance role. It was not practical or possible to launch a heavily ladened bomber.

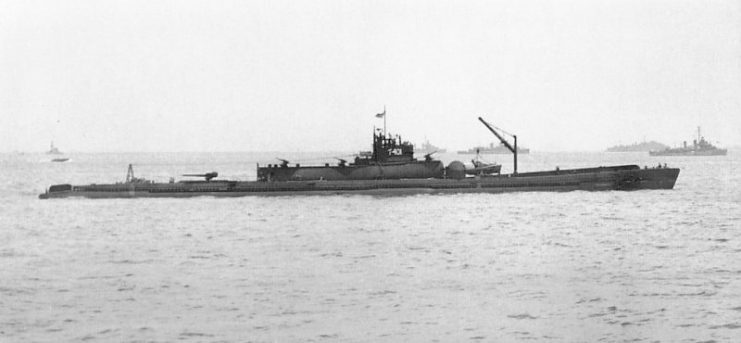

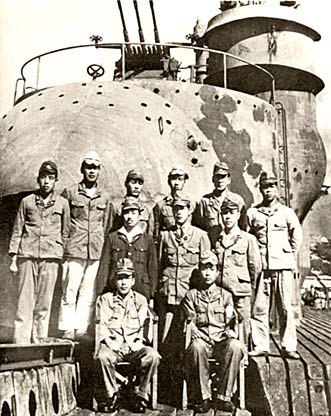

The amount of aircraft one of these huge submarines could carry was pitiful. The Japanese submarine aircraft carrier of the I-400 class weighed 9,000 tonnes and was 400 feet long, but could carry just three fighter-bombers.

Furthermore, the aircraft it carried were pretty badly performing floatplanes that were slow, incredibly poorly armed (just one heavy machine gun), and could barely carry 1,000lbs of bombs.

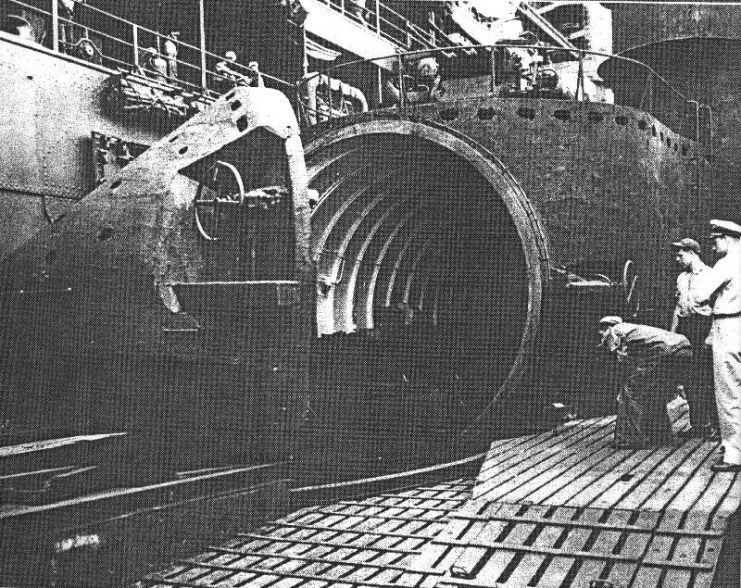

This class of submarines was astronomically expensive and inherently unsafe due to the large hanger doors and the vessel’s poor maneuverability.

In addition, the preparation, loading, and retrieval times for the submarine carrier aircraft was exorbitant. The I-400 class had to use a 120 feet crane to launch its three planes, an operation that took about 45 minutes.

After the war, the concept was abandoned, and countries instead invested in much more practical long-range bombers or the hugely expensive but flexible and powerful conventional aircraft carrier.

- Kamikaze Bat Bombers

American: 1941 to 1944

The difference between a Japanese pilot going on a suicidal Kamikaze mission and strapping a miniaturized bomb vest on a small flying mammal is that the Japanese pilot knew what he was signing up for. In contrast, the bat was none the wiser as to what was going on.

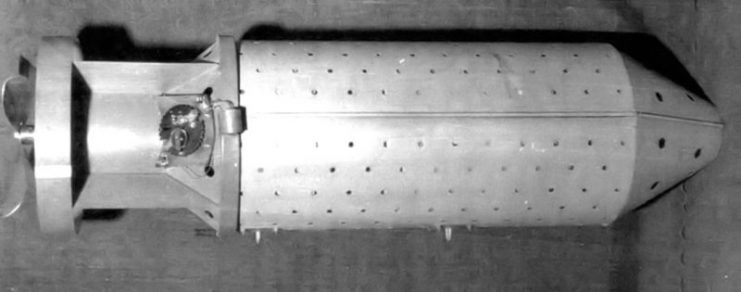

The idea, as crazy as it seems, was to drop from a bomber scores of sleeping bats (Mexican free-tailed bats to be precise) at dawn. Attached to each bat was a small incendiary bomb with a timer. The bats would all be in a single large canister that, halfway down, would deploy a parachute and then set the bats free.

The theory went that the disorientated and confused bats would wake up before they hit the ground. Realizing the night was quickly coming to an end, the bats would instinctively disperse and find somewhere to roost. It was hoped that they would head to the rooftops and attics of the large cities they had been dropped over.

Once they had found somewhere to sleep, a short while later the timed bombs would go off. It was anticipated that the flaming bat would then set light to the combustible paper and wooden buildings that were so popular at that time in Japan.

Did it work? Well, surprisingly enough, it did work well in tests, but progress was slow for a number of reasons, and the project was canceled in 1944.

Though the idea was innovative, its chief drawback was that a normal bomber could do (and had been doing) the job more easily by simply dropping an incendiary bomb and letting gravity do the rest

- The Krummlauf– Curved barrel attachment

German: 1944 to 1945

During World War Two, the Germans found that urban warfare, especially on the Russian front, was both brutal and costly. Desperate, they looked for any innovation that might give them an edge in this kind of environment.

As a result, they came up with the novel idea to fit a reinforced curved barrel attachment to the Sturmgewehr 44 assault rifle (the gun that was later to be the inspiration for the legendary AK-47).

The attachment had a 30-degree curve, and the idea was that, with the aid of a mirror sight, you could theoretically aim and fire around corners.

Maybe the Krummlauf attachment was one of these ideas that looked better on paper because in reality, it was far too complex an idea with no real benefit.

The weapon, when fitted with this attachment, could not be used as a conventional weapon. It was also almost impossible to aim around a corner with any accuracy, and the barrel attachments wore out after just a few hundred rounds.

The attachment had a nasty habit of exploding as the bullet sometimes went straight ahead, piercing the curved barrel wall and shattering it to pieces.

Even though this concept never really worked well in combat and was deemed a failure, modern weapons manufacturers are revisiting how to fire around corners, and many companies are looking at adding attachments to handguns.

One successful system is the CornerShot accessory which uses a digital camera. The barrel is not curved but instead, the barrel and trigger are separated by a 60-degree joint. This system is starting to be adopted in increasing numbers.

- Supermarine Scimitar- Carrier Based Strike Fighter

British: 1957 to 1969

If you are going to complicate an aircraft, you would at least expect it to be all worthwhile, perhaps resulting in an aircraft that ruled the skies.

Well, the Supermarine Scimitar ended up being a complex and incredibly high maintenance British carrier based strike fighter. But was it any good? In a word: no.

It was a nightmare of an aircraft with distinctly lackluster performance. It was difficult to land (a serious drawback for a carrier-based aircraft), its complex fuel system generated numerous leaks, and over half of these aircraft were lost to accidents in its short service career (a little more than ten years).

When compared to contemporaries like the American Vought F-8 Crusader that was introduced in the same year, it was already obsolete when it entered service. The Crusader was the same size and weight as the Scimitar, but it was 60% faster, could fly 26% higher, climb 260% faster, and had a fire-control radar.

Read another story from us: Battleship Yamato’s Final Kamikaze Mission

The Scimitar was relegated to second-line duties just five years after it had entered service, and less than 80 of these were built.

So, will something like the new F-35 Lightning II program be seen in hindsight as a much-needed and valuable weapon system? Or will it be judged as a plane that was made far too complex in an effort to make it the aircraft that means all things to all countries?