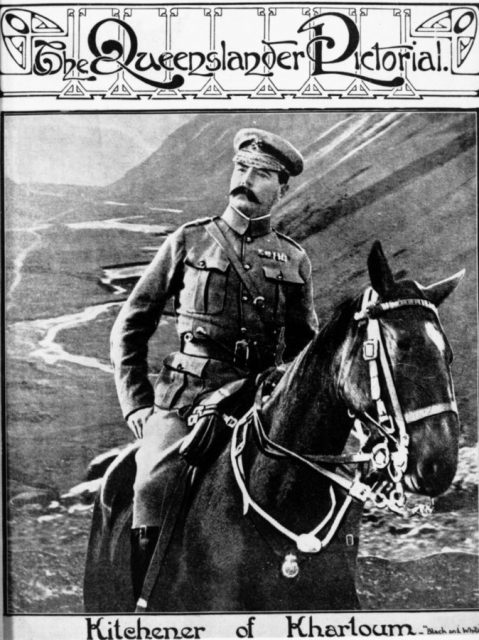

The second Anglo-Boer War, also called the South African War, started on 11 October 1899. Two young Boer republics were pitted against the might of the British army in a David versus Goliath scenario.

Gold had been discovered in the Witwatersrand in the Transvaal in 1886 and by 1890 South Africa became the single biggest gold producer in the world. This fueled the ambition of Cecil John Rhodes and the British government to unite South Africa under their rule. It was imperialism against republicanism with tons of gold at stake.

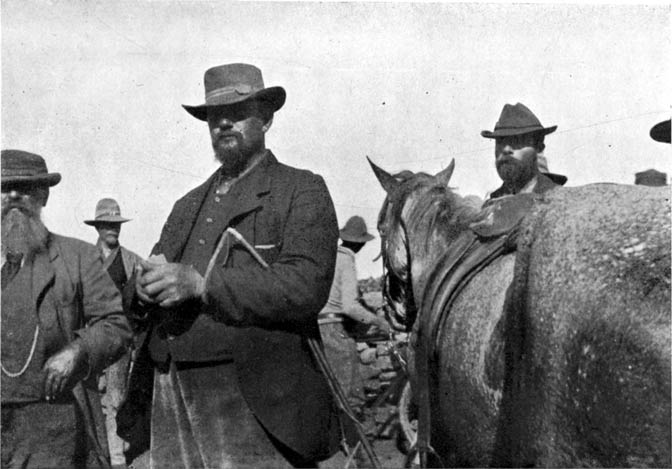

The Boers were mostly Dutch descendants who left the Cape Colony (the southern tip of Africa) during the 19th century to settle in the Orange Free State and the Transvaal (together known as the Boer Republics). They left to escape British rule and get away from the constant border wars that went on between the British imperial government and the indigenous peoples.

The end of this war is significant in that it marked the end of the British conquest of South African societies.

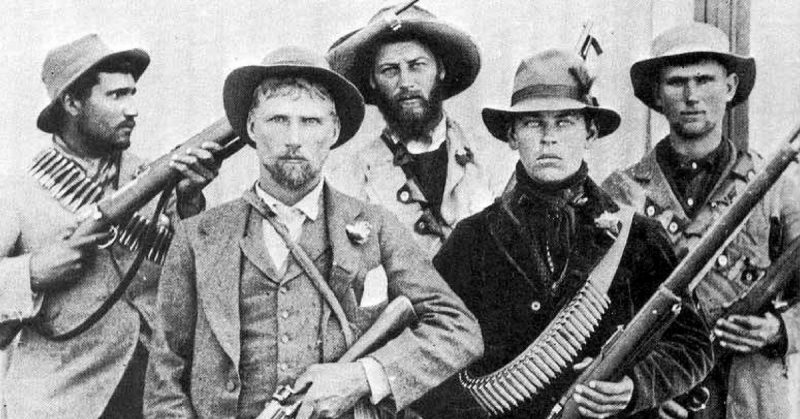

The Boer Republics (the Orange Free State and the South African Republic or Transvaal) were newly-formed, informal groups of people seeking a form of nationhood that was more a response to their rejection of British rule than a clear vision of what they wanted. They did not have a formal army and all capable men were called to fight in the war.

These men were loosely organized in what was called ‘commandos’. A commando had a clear leadership structure that was built around a strong, often stoic personality that commanded great loyalty from his followers. The ‘clear’ leadership structure was, however, was defined as much by the strong-willed farmers whose characters were shaped by the struggle of taming a new land and settling their farms. Orders were often debated by everyone and it certainly did not even have the appearance of a regular army. No uniforms were even worn.

The guerrilla tactics pursued by these commandos frustrated the conventional forces of the British endlessly and is an interesting study. It was birthed in desperation and the personalities of the men who formed and led the commandos. A look at how discipline was managed will give some insight into these personalities.

The story is told of a group of citizen-soldiers who, while on guard duty, slaughtered an ox and started a braai (BBQ) against explicit orders. This was discovered, and a higher-ranking soldier was sent to discipline them. He ended up joining the braai. Two more soldiers of ever-increasing rank were sent one after another. They both ended up joining the braai. All of them were punished in due course but considered it well worth the punishment and the risk in a time of war.

This proclivity for a good braai is a strong South African tradition to this day, unifying all its cultures.

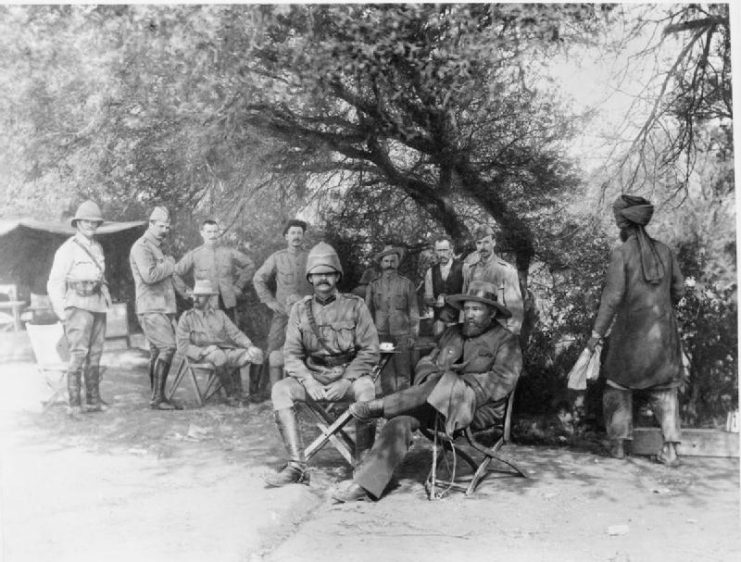

As in any army, discipline, however informal, was important. A military court was constituted and available but mostly justice and punishment were a swift thing that took place on the move. A stationary commando was very vulnerable.

There were regular punishments that we would be familiar with today. Severe fines were possible. Theoretically, someone could be jailed but, mostly due to the severe lack of manpower, that was exceptional.

In April 1902, two citizen-soldiers were convicted of stealing dried tobacco leaves from a widow on a farm. They were sentenced to seven days confinement to the laager (a defensive circular encampment formed by wagons or vehicles) and had to return half the tobacco leaves.

Other punishments were less conventional, and are interesting to consider.

A light punishment is described as ordering someone to march around the laager with his saddle, gun, ammunition belt and other paraphernalia on his back or head. This could last anything from 30 minutes to two hours with everyone in the laager shouting comments attempting to shame the guilty individual.

A more severe punishment was known as ‘beesvelry,’ loosely translated as ‘riding a cowhide.’ The hide of a freshly slaughtered cow would be held stretched out by about 10 men. Holes would be cut all around to facilitate strong grips for each man and the bloodied side would face up. The individual being punished would be laid on the hide and then be shot into the air by the men pulling the hide tight.

A crowd of shouting soldiers would loudly encourage this activity until the officer in charge felt the poor guy had suffered enough. The hide would be taught as a drum when he came down and he ended up scraped and bruised. However, this was sometimes done in fun too, though for shorter periods and rarely, if ever, when sober.

It goes without saying that this form of punishment did not exist in the British army of the time, nor in any modern army today.

An even worse punishment was a ‘canon ride’. The soldier being punished was tied onto the barrel of a canon, his legs around the barrel and his hands behind his back. This was done in the march and sometimes the poor guy was not even allowed pants.

The wide barrel moving over uneven terrain and becoming very warm in the sun created severe discomfort while everyone within sight shouted at and derided him. It lasted about an hour but caused pain and an uncomfortable but funny walk for days after.

The officers in this rag-tag army had an unenviable position regarding discipline. They were desperate for every man and most were related to one another on one level or another. The strong-willed pioneer spirit of these men also meant that discipline seen as too harsh would lead to rebellion.

There were many verbal reprimands and a lot of discussions. And much motivating was done. Some of the most renowned leaders of this army were successful because of their ability to unite their men with a rousing speech. As you can imagine, this was not a very sustainable way to operate.

Inexperienced officers had to make finely balanced judgment calls on who to discipline and how severe the punishment ought to be. Involving the whole group in shaming the guilty party, as described here, created a sense of camaraderie and sometimes some much-needed levity. It was a unique war that required some unique methods.