Even the best of commanders are prone to poor performance when ill health strikes. Several of note have affected the French army during its history. As this short list shows, even the greatest of men can be laid low when their bodies betray them.

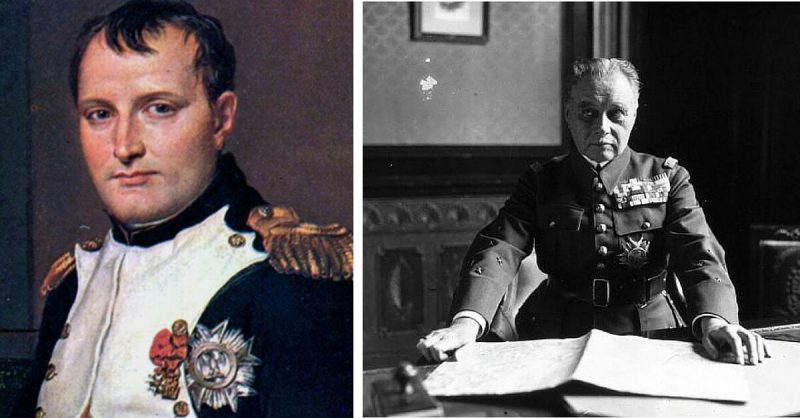

Napoleon Bonaparte

Napoleon was, without a doubt, an extraordinary general. Innovative, calculating and determined, he marched his armies to triumph in wars of unprecedented scale and complexity. But as the years passed, endless campaigning took a toll on his health. His body began to fail, providing an extra distraction that contributed to his crumbling control over Europe.

From 1807 onwards, the previously energetic general began to show signs of ill health that affected his performance. Suffering from colic and then a peptic ulcer, pain from his organs caused his temper to worsen and his mind to slow. He was commanding some of the largest armies the world had ever seen, as his campaigns transformed the face of European warfare, but his ability to manage a complex situation was worsening.

By Borodino (1812) Napoleon may have had trouble riding, due to a bladder complaint. The next year, at Dresden and Leipzig, stomach pains distracted him, and the little Corsican was seen doubled over with pain. When not in pain he was exhausted, possibly as a result of a pituitary disorder, and after Leipzig he was so tired he could not organise an effective retreat.

As Geoffrey Regan puts it, “At his best he was still incomparable, but his good days were becoming too rare.” At Waterloo, he suffered an extra indignity, prolapsed piles making it painful to mount his horse.

Major d’Alenson

In December 1916, the French forces on the Western Front of the First World War gained a new commander-in-chief, General Robert Georges Nivelle. Nivelle brought a reputation as a capable commander though one willing to throw away lives in the name of victory. He also brought his chief of staff, Major d’Alenson.

D’Alenson’s days were numbered, but not because of the war. He was suffering from consumption and knew that it was going to kill him. A proud patriot, he was determined to do something significant for France before he died. His obsession influenced Nivelle, and together they planned what would become the Nivelle Offensive. D’Alenson’s illness-driven obsession would end up costing thousands of men their lives, and his superior his command.

Many senior officers cast doubts on the planned offensive, which was meant to strike a decisive blow against the Germans. But Nivelle was not to be deterred and cancelled other offensives to ensure that his could take place. Even when Germans captured a copy of his plans on 4 April 1917, the general pushed ahead.

Launched on 16 April, the offensive was a disaster. The French suffered ten times as many casualties as Nivelle had predicted. From the very first day, they failed to achieve their targets. Yet the offensive continued, to the astonishment of the Germans. With the attack stalled and the French officers losing control, Nivelle became increasingly depressed. The aims were reduced, and the offensive finally halted on 9 May. 187,000 French had died failing to fulfil d’Alenson’s dreams of victory. On 15 May, Nivelle was replaced as commander-in-chief by General Pétain.

General Maurice Gamelin

Prior to the Second World War, General Maurice Gamelin was widely respected by both allies and opponents. A veteran of the First World War, he was credited with much of the planning that led to Allied victory at the First Battle of the Marne in 1914. During the inter-war years, he became head of the French general staff, in which role he oversaw steps to modernise and mechanise the army. His period of leadership also saw the creation of the Maginot Line, the flawed defence system that would prove crucial in France’s fall to Nazi Germany.

At the same time that he was commanding the French army, Gamelin was suffering from neurosyphilis, an advanced form syphilis that affects the brain. Symptoms include lapses in concentration, memory, judgement and intellect. Gamelin’s own memoirs would reveal evidence of both paranoia and delusions of grandeur. How far this contributed to Gamelin’s greatest failure is impossible to prove, but it certainly made him a liability as the man in charge of the army.

The failure for which Gamelin is remembered came in 1940 when Germany invaded France. Gamelin’s flawed planning and conservative leadership left the initiative with Germany and meant that opportunities were missed. As the French were driven back, he sacked twenty front line commanders, scapegoats for his failure, rather than accept that his plan had been flawed. France was overrun in just six weeks, and Gamelin spent the war in captivity.

General Georges

France was doubly unlucky in its general during the German invasion. Gamelin’s deputy and the commander of French forces in the field, General Alphonse George, was another once great soldier who had been affected by ill health.

Seriously wounded early in the First World War, George spent the remainder of the conflict in the general staff and continued to serve in command positions after the war. In 1934, he was wounded once again, this time during the assassination of King Alexander I of Yugoslavia by a Macedonian separatist. The injuries proved severe, and by 1940 he was still suffering from the after-effects of the attack. As the Battle of France would prove, his scars were emotional as well as physical.

Along with Gamelin, Georges assured French politicians that they could defeat the German invaders. But as the national defence unravelled, so did Georges’s mental health. When it became clear that the Nazi’s were winning, other officers saw Georges – the man who should have been commanding the practicalities of withdrawal and regrouping – break down in tears.

Sources:

- Regan, Geoffrey (1991), The Guinness Book of Military Blunders.

- Wikipedia, accessed 11 January 2016.