We all know that gunpowder weapons exploded onto the scene in the middle ages and changed warfare forever. But how exactly did they change battles and who used these almost magical weapons to their greatest effect? We know that massive cannons changed sieges – the final fall of Constantinople was achieved with great bombards, but what about field battles? In a bizarre period where armies marched with armor, pikes, cavalry, cannons and muskets so heavy they needed stands, Gustavus Adolphus aggressively innovated like no one had before.

Gustav certainly had a celebrated and admired career. He was known as Gustav the Great, The Golden King, and The Lion of the North. We are going to talk about his military exploits, but it is important to note that Gustav completely reformed Sweden’s government, economy, and society. He pulled Sweden out of the middle ages and put them on a fast track to the modern era.

Gustav entered his military career in a major transitional period of European warfare in the early 1600s. Guns were still heavy and required lots of training to use correctly and often required stands to be aimed. The lines of battle were typically masses of infantry supported by static heavy artillery and cavalry charges. Muskets were certainly effective, but pikes still saw massive use as they could be quickly reused in all weather and were excellent cavalry deterrents.

Gustav set out to create a professional army with exceptional synergy and flexibility. First, each segment of the army had equal status and emphasis. In a world where cavalry was usually held in high esteem and infantry were looked down on with disdain, equality among troops made them fight better as a whole.

Gustav also ensured that every type of soldier was comfortable taking any other role on the battlefield. Known as cross training, it meant that a pike soldier was well trained with his pike, but also trained enough that he could comfortably pick up fallen musket and fire, something Gustav’s pikemen often did as an early strike against cavalry charges. Cavalry could also effectively charge enemy cannons and take control of them, turning them on the enemy.

Where other European armies had distinct formations of units, such as pike squares and cavalry at the wings, Gustav employed combined arms tactics. Lines of muskets would be supplemented with a few pikemen to give them some melee strength. Cavalry were also able to charge out from, and retreat back to, the safety of infantry formations.

Gustav’s lines were also much thinner and organized in smaller groups. He still used the heavy cannons so popular on the battlefields but also used much smaller pieces of field artillery. Though it seems obvious now, European commanders of the period used heavy, inaccurate cannons that were very difficult to move during battles. Gustav’s light cannons were easier to move, aim and reload and though the shot was smaller, they were still many times larger than a musket ball and tore through enemy formations at close range. Furthermore, these light artillery pieces were far from static and moved all over the battlefield, making it difficult for enemy commanders to predict where they would face the most fire.

Finally, though not the last of his innovations, Gustav simplified the musket for his army, making the gun light enough to use without a stand. He also streamlined the reloading processes, greatly increasing the rate of fire possible.

All of these developments turned Gustav’s army into a flexible and extremely aggressive fighting force. Mobile artillery could be moved up to weaken the other side’s cannons, which could then be taken with a swift cavalry charge and turned on the enemy. Such a sequence of events was unique to Gustav’s army for many years.

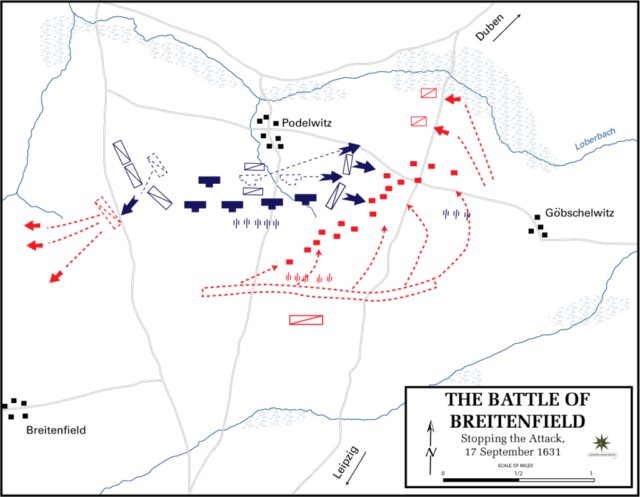

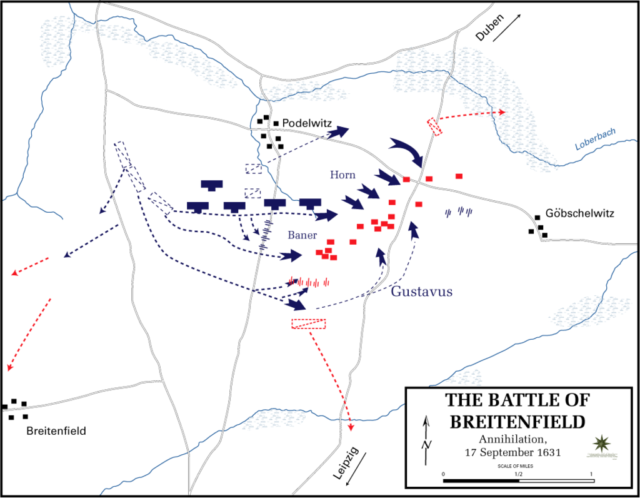

The Thirty Year’s War became a showcase of Gustav’s talents. Gustav, fighting against the Catholic League for the Protestant countries, hadn’t fought a major European battle of note until the Battle of Breitenfeld in 1631. The Catholic League was led by the Count of Tilly, an extremely accomplished general during this period. Fighting with some allied Saxons guarding his left flank, Gustav let the troops of the Catholic League make the opening moves.

The Catholic League made the right move in heading straight for the Saxon flank, almost immediately routing the Saxons and exposing Gustav’s flank. Rather than wait for his flank to be torn open, one of Gustav’s commanders charged into the disorganized line of the formerly victorious Catholic League.

The lines of battle rotated as Gustav himself led a cavalry charge against the canons of the Catholic League, taking them, and firing on the rear ranks of the League. After trying to fight their way out, the Imperial Catholic League finally broke and ran. In the end, the Catholic league lost over half their forces killed, wounded or captured including all of their artillery. Gustav had burst onto the European scene with a bang. During the battle Gustav boldly lead with just a leather cuirass to inspire his troops, but was shot in the shoulder. He survived but carried the bullet with him the rest of his life.

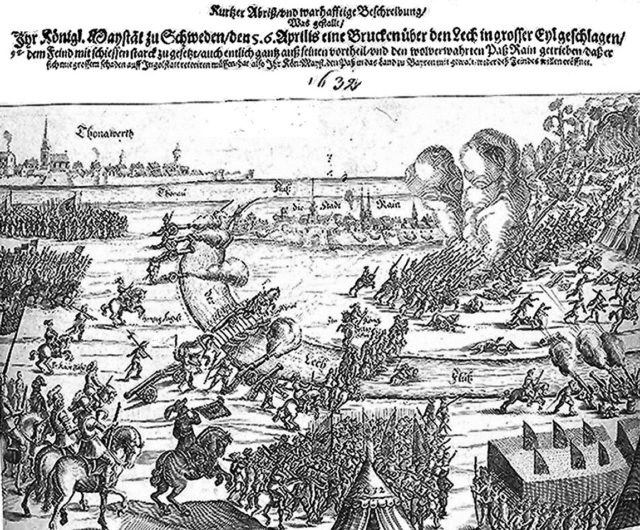

The next battle also pitted Gustav against the Count of Tilly. At the Battle of the River Lech, Gustav was able to aggressively cross the river using well-placed artillery fire. With feint attacks and well-fortified positions to ward off counter-attacks, the Swedish assault was far more successful than anyone could have thought. It was so successful that the Count of Tilly was mortally wounded early in the battle, and his second in command killed shortly after, causing an early general retreat. Though the loss of commanders and 3,000 men was terrible for the Catholic League, had they stayed they would have been completely surrounded as Gustav had snuck multiple units across the river in wide flanking maneuvers.

Unfortunately for Sweden, the career of Gustav Adolphus was cut far too short at the Battle of Lützen in 1632. Again facing the Catholic League, Gustav’s men fought in extremely heavy fog with largely equal troops on each side. Being the same brave leader, Gustav led a cavalry charge wide on the Imperial left. Somewhere among the heavy fog he was shot and killed.

It is unclear how many of Gustav’s troops knew of his death, but the second in command was determined to win the day for his deceased commander. In a brutal slogging battle, the Swedish eventually won the field as night fell. Gustav’s death severely derailed the Protestant cause. The Swedish Empire still maintained its power, but the Protestants had to fight on through a merciless war for many more years before an amicable peace could be established.

He was deeply mourned. His leather coat was preserved and his famous warhorse, Streiff, was well taken care of and was preserved after its death. Even today, Swedes remember Gustav by having a celebration of their great leader every year on the anniversary of the battle, November 6th. Even the heavy fog on the day worked its way into the Swedish language where heavy fog is simply called Lützen fog.