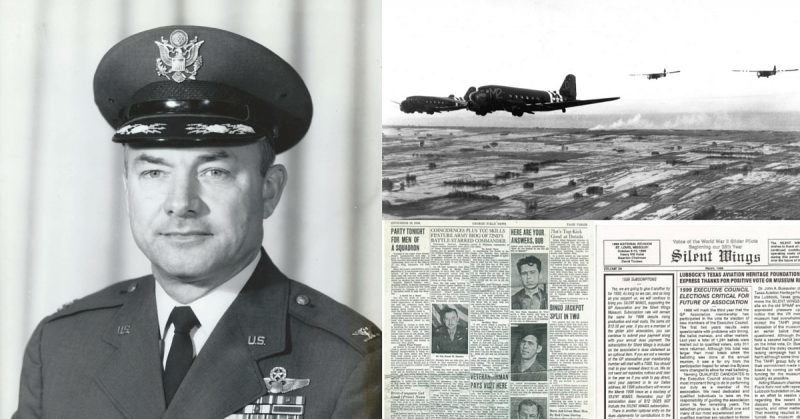

In memory of Col. Frank W. Hansley (1917-2003)

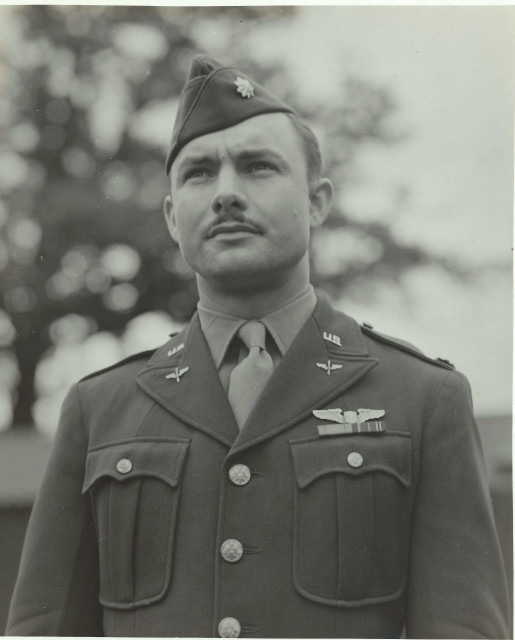

Air power was a key component to the Allied victory in WWII. The mobility and maneuverability of airborne infantry dropped behind German defenses was a vital piece of the D-Day invasion.

Tactical bombings of German military positions aided in the expansion of the Allied front in mainland Europe. Strategic bombing of German infrastructure, including oil and ball bearing production crippled the German war machine, causing the Wehrmacht war economy to implode by the winter of 1945.

Allied air forces also carried out logistical duties, delivering supplies and mail to the front. Before returning to their airstrips, these planes would gather men who were injured in combat and fly them back to doctors and nurses waiting in nearby hospitals.

Colonel Frank W. Hansley spent 30 years of active service in the United States Air Force. He was 24 years old when he left Heidelberg College in Tiffin, Ohio to enlist in the U.S. Army Air Corps in 1941. He quickly earned his wings and in 1942, with the rank of captain, was assigned as an operations officer of the 72d Squadron in the 434th Troop Carrier Group.

When the 72d Squadron took off to carry out assault missions in the D-Day invasion of Normandy, “In the lead ship of the squadron (and also commanding officer of the organization) was then—Major Hansley,” reported the November 10th edition of the George Field News in 1945 (pg. 3).

During the Normandy invasion, the 72d Squadron dropped paratroopers and towed gliders over enemy lines. Col. Hansley told the newspaper that “We made three missions in less than two days but were very fortunate. The squadron suffered no losses on any of the missions” (pg. 3).

After the successful invasion of mainland Europe, Col. Hansley’s squadron was tasked with combat resupply, casualty evacuation, and logistical functions.

He told the George Field News, “One of our most appreciated functions was the mail flown to France in C-47s. Sometimes the boys in France actually received better a mail service than those in England” (pg. 3). After Normandy, Col. Hansley’s missions of assault, frontline resupply and air evacuation of wounded continued in areas such as Holland, Bastogne, and the Rhineland.

The 72d Squadron also airdropped supplies and evacuated wounded during the Battle of the Bulge. Col. Hansley had some close brushes with death, especially while he flew over Holland.

Troop carrier squadron air assault, combat resupply and medical evacuation missions required low-altitude flight; the planes flew low enough for ground fire and flak to be a danger to the aircraft and crew.

He told the George Field News “My closest call came at that time when my wing man was knocked down…In March, a fragment sailed through my wing, luckily too far out to hit the gas tanks” (pg. 3).

When WWII ended in an Allied victory, Col. Hansley returned to the United States and married Jane Charles, who would be his wife for 56 years.

With his wife and their two children, Col. Hansley assumed various USAF command positions and was stationed at bases in the Pacific and mainland United States. He served in the Tactical Air Command, then Strategic Air Command and eventually was assigned to Air Training Command.

After serving in WWII, the Korean War and the Cold War, Col. Hansley retired from the Air Force in 1970, at the age of 53. The B-52 was the last aircraft Col. Hansley flew for the Air Force. He and his family eventually settled in South Carolina.

Upon retirement, he had been decorated with the Legion of Merit, Distinguished Flying Cross, Air Medal with oak leaf cluster, Air Force Commendation Medal with oak leaf cluster, Presidential Unit Citation—Battle Honors, Air Force Outstanding Unit Award, American Defense Service Medal, American Campaign Medal, Europe-Africa-Middle East Medal with silver and bronze stars, World War II Victory Medal, National Defense Service Medal with bronze star, Korean Service Medal with bronze stars, Air Force Longevity Service Ribbon with silver and bronze oak leaf clusters, Korean Presidential Unit Citation, and the United Nations Korean Medal. Col. Frank W. Hansley passed away in 2003 at the age of 86.

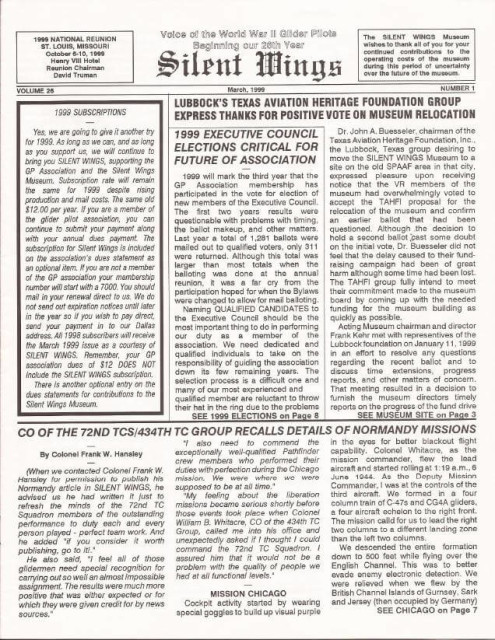

In 1999, the 26th volume of the Silent Wings newsletter published Col. Frank Hansley’s recollections of his missions over Normandy (Missions Chicago, Keokuk and Galveston) as well as his resupply and medical evacuation missions in the aftermath of the initial Normandy invasion.

His descriptions are both incredibly detailed and filled to the brim with emotion and imagery. His account of his experience in Normandy is transcribed in its entirety below.

Images of the George Field News and Silent Wings can be found at the end of the article.

“CO of the 72nd TCS/434th TC Group Recalls Details of Normandy Missions”

“When we contacted Colonel Frank W. Hansley for permission to publish his Normandy article in SILENT WINGS, he advised us he had written it just to refresh the minds of the 72nd TC Squadron members of the outstanding performance of duty each and every person played – perfect team work. And he added ‘if you considered it worth publishing, go to it!’”

“He also said, ‘I feel all of those glidermen need special recognition for carrying out so well an almost impossible assignment. The results were much more positive than was either expected or for which they were given credit for by news sources.’”

“’I also need to commend the exceptionally well-qualified Pathfinder crew members who performed their duties with perfection during the Chicago mission. We were where we were supposed to be at all times.’”

“’My feeling about the liberation missions became serious shortly before those events took place when Colonel William B. Whitacre, CO of the 434th TC Group, called me into his office and unexpectedly asked if I thought I could command the 72nd TC Squadron. I assured him that it would not be a problem with the quality of people we had at all functional levels.’”

“Mission Chicago”

“Cockpit activity started by wearing special goggles to build up visual purple in the eyes for better blackout flight capability. Colonel Whitacre, as the mission commander, flew the lead aircraft and started rolling at 1:19 a.m., 6 June 1944. As the Deputy Mission Commander, I was at the controls of the third aircraft echelon to the right front. The mission called for us to lead the right two columns to a different landing zone than the left two columns.”

“We descended the entire formation down to 500 feet while flying over the English Channel. This was to better evade enemy electronic detection. We were relieved when we flew by the British Channel Islands of Gurney, Sark and Jersey (then occupied by Germany) without any enemy response.”

“As we approached the French coast, I hoped the many fires I saw ahead were a good sign that the fighters/bombers had knocked out most, if not all, enemy gun emplacements. That hope did not last long! Our lead aircraft flew a very short distance over land before streamers of tracer bullets started whizzing around the aircraft and gliders. I started telling myself, ‘keep the faith, keep the faith!’ I then added and repeated my version of the 23rd Psalm which was “Yea though I fly through the valley of death I fear no evil for Thou art with me.’ With this true belief, it proved most calming! I am positive many others in our formation were doing much the same – all stayed the course!”

“As one string of tracers moved within inches of my aircraft, a strange question flashed through my mind – how will it feel when the bullets rip through my body? The firing stopped just before striking the aircraft!”

“I glanced around at the aircraft crew and found each of them calm and doing his job. My version of the 23rd Psalm became plural: ‘Yea though we fly through the valley of death…etc.’”

“I was concerned about others in our formation. If we in the lead aircraft were attracting so much enemy fire power, what is happening to those following us? There was no way of checking! We had to maintain radio silence; however, those aircraft flying off of our wings seemed to be faring well.”

“We came to the predesignated point at which we would lead approximately 50% of the mission aircraft and gliders to a secondary landing zone. With the blackout, it was impossible to see good navigational landmarks as it was 4:00 a.m. No problem! Our aircraft had one of the latest electronic navigational units – known today as LORAN. By automatically calculating the triangulation of three English-based radio station signals, it could indicate our location within an acceptable few yards.”

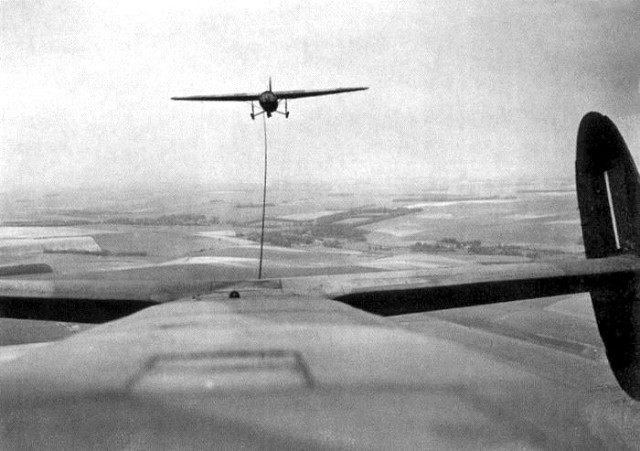

“As we approached the landing zone (LZ), we anxiously looked for the ground signals from the Path Finder Troops that had been dropped earlier by another unit. As we prepared to release our gliders without that verification, their signals were activated. They were a radio beacon and the lighting of a landing tee.”

“Those signals were wonderful assurances, but it did not relieve my great concern for the glider crews and troopers. Darkness would not give the glider pilots the visibility to select the safest landing routes. I truly regretted they had to release. The odds were very high against them.”

“We intercepted and then accompanied Colonel Whitacre’s two columns for the flight over UTAH Beach and the mammoth Allied landing fleet – IFF (Identification, Friend or Foe) assuredly turned on! The return flight to Aldermaston was uneventful.”

“Mission Keokuk”

“After a short relaxing nap at the flight line, it was time to man the 32 tow planes and the English-made Horsa gliders for the Keokuk mission. Take off started at 6:30 p.m., 6 June 1944. As deputy mission commander, I took off in the second aircraft and flew off the lead aircraft’s right wing. Lt. Col. Steve Parkinson was flying the lead aircraft as mission commander.”

“Nothing unusual happened en route. My memory flashes back to a rather open route leading over Utah Beach and a trail way pretty well controlled by advancing American troops. Appreciatively, we received much less ground fire on this mission, even after we arrived over the glider landing zone area. We were later informed that the Germans saved their ammunition to use on the attacking glider men during their approach and landings. I sure saluted the glider men; they again took the brunt of the mission.”

“Once again, the return flight to Aldermaston was uneventful.”

“Mission Galveston”

“The first tow planes with gliders took off at 4:32 a.m., 7 June 1944. We had rain, gusty winds and poor visibility. I was leading the 72nd Troop Carrier Squadron element, which was the third unit in our train of 50 towed CG4A gliders. The weather cleared for much better visibility over the channel. Unlike Keokuk, we received much enemy ground fire as we entered French territory. I do not remember many other details of this mission, except that some earlier gliders had landed in deep marshlands. I tried to give the glider pilots the best possible landing approach over land, yet keep them together as one fighting unit.”

“Resupply”

“We started within days, landing on rapidly built strips near the battle front lines. We flew in food, ammunition, blood plasma, gasoline, and other required materials. Flight nurses became very important members of the aircrews.”

“Two incidents still stay strong in my mind. I led a flight onto a strip with enemy guns flashing just off the east end of the strip. As we started unloading the aircraft, the Germans started dropping .66 mm mortar rounds onto the strip. Crew members hit the troop trenches! No persons or aircraft were lost, so we finished unloading supplies, then loaded battle-wounded personnel for the flight back to England and hospitals.”

“Another well-remembered resupply mission was one to the Canadians near Caen, France. I could not believe the number of burning tanks, most of them from the 21st Panzer Division. It was a frightening sight of destruction.”

“The 72nd Troop Carrier Squadron men, of all specialties, performed superbly! A true top-performing unit!”

__

“We appreciate receiving permission from Colonel Hansley to publish this excellent summary of the early Normandy missions. The Chicago mission was flown by 52 CG4A gliders from the 434th TC Group. 72nd TCS personnel flew 11 of the 12 gliders flown by the squadron. The lead glider was flown by Colonel Mike Murphy, with 2nd Lt John M. Butler as co-pilot.”

By C. Keith Hansley—Read all of his articles at http://historianhut.blogspot.com