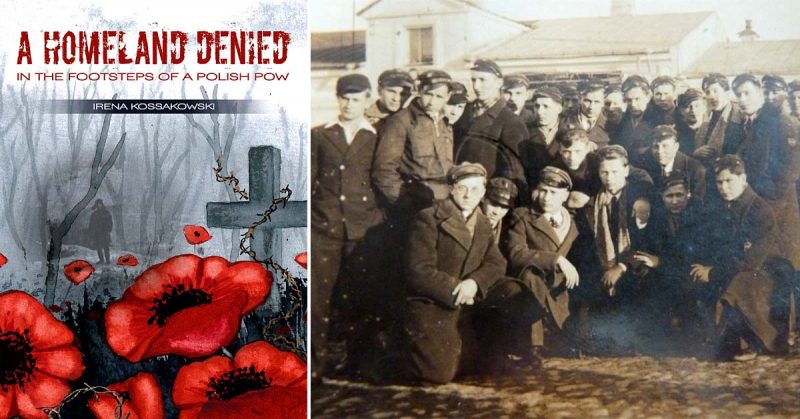

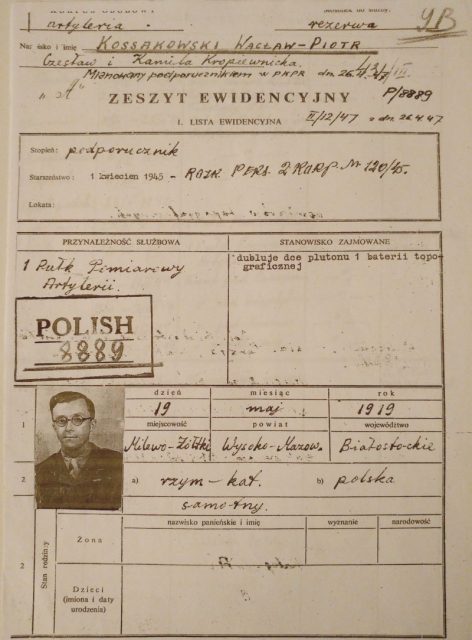

Illustrated with photographs and documents, “A Homeland Denied: In the Footsteps of a Polish POW ” is not just a military history book. It is the story of my father and those left behind in Poland during and after WWII.

It is about his family – his mother and his two brothers forced to live in a mud bunker when the Russians occupied their farmhouse. It is about the resistance and the Warsaw Uprising, and the girlfriend he hoped to marry. It details why they could not return home and what life was like after the war in Communist Poland and in the resettlement camps in England.

Told with flashbacks it gives a fascinating insight into a life long gone. His school, his friends, and events that happened not just in Poland but elsewhere so the reader can identify with where he was.

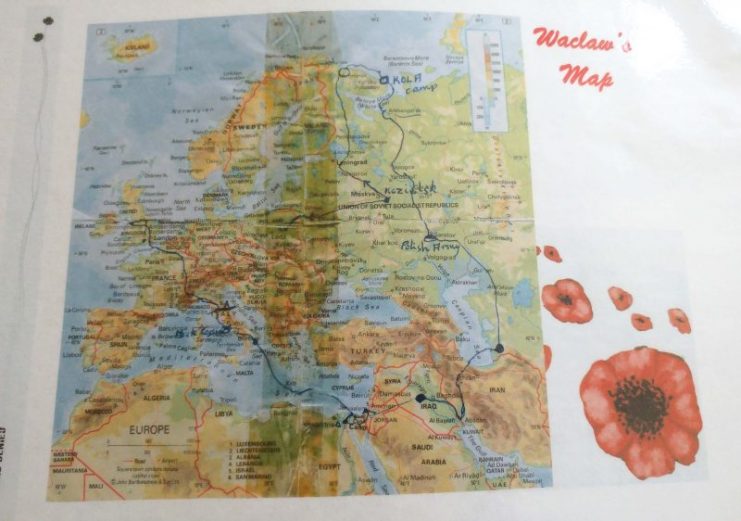

Waclaw Kossakowski grew up on his family’s farm in a small village near Biarytok, eastern Poland. In 1939, aged 19, he was studying physics at Warsaw University. He and his friends joined the army cadets in Suwalki, close to the Russian border. Seventeen days after Germany invaded Poland from the west, Russia invaded from the east. Dad was taken to Kozielsk prison and interrogated for several months. It was at that prison that so many were shot and taken to the Katyn forest, buried in a mass grave. Dad knew what was happening and once said, ‘No one bothered to ask me.’ For years this atrocity was blamed on the Germans by the Russians.

After enduring the months of interrogation, the men were moved to Siberia. They were transported in cramped cattle trucks to the furthest northern labor camp on the edge of the Kola Peninsular and within the Arctic circle. Camp Kola, dad called it, where the ground is always frozen even in summer. The Russians did not abide by the Geneva convention; there was no medical aid, no letters, no food parcels. Every day they worked for 15 hours in temperatures as low as -50, building runways.

In 1941, Germany surprised Russia with an invasion, attacking its frontiers. My father and the others were freed but only to fight for the Russians on the Eastern Front. They were moved across southern Russia to the Tatiszewo internment camp where conditions were almost as horrific as in the labor camp. General Wladyslaw Anders knew they would die if they remained under Russian control. Through an agreement with the British Prime Minister, Churchill, the Poles were again transported across the Russian steppes and the Caspian Sea to the Middle East. There they joined the 2nd Polish Army Corp under the 8th Brtish Army.

In 1944, dad fought in Italy at Monte Cassino; Ancona; Piedmonte; and Bologna. But after the war, he could not return home as anyone who had fought against the Russians was considered their enemy and Poland was by then a truly terrible place to live, governed by Russia. The former soldiers were given a choice: America, Canada, Australia or England.

Dad chose England, as it was closest to Poland and he hoped to return there before too long. However, it was not possible, and while studying at Nottingham University, he met my mum, Irene Clarke. They married, and he became the father of identical triplets.

Sadly, he never got to see his father again, as he was unable to visit Poland before 1966. His mother lived to be 100. My father died aged 94 on the Isle of Wight, England. Before then, he met the Polish Pope, John Paul II.

Below is an extract from the book. My mum always called dad Vadek as it was easier to say – Waclaw is not pronounced how it looks. Vadek has newly arrived at the labor camp.

Vadek lay on the hard wooden board that was his bed and, folding his hands behind his head for a pillow; he closed his eyes. Exhausted and hungry he tried to think of anything but food. He remembered his comrades at Warsaw University and the last time they had all been together. He remembered his good friend Patryk. A year older than him, he had signed up immediately to join the cavalry. Was he still alive? There was no way of knowing. There had been such terrible rumors. Were any true?

Everyone had heard of the bravery of the Polish cavalry. On the very first day of the invasion, their traditional charge had successfully dispersed a German infantry battalion a few miles from Krojantry. Minutes later they had been surrounded by armored cars that had approached unseen from the nearby forest armed with machine guns.

Wholly exposed in the clearing they had been forced to gallop for cover. Horses hooves thudded on the hard ground, churning the earth into large clods of mud that flayed the air as they frantically raced for shelter from the murderous onslaught. Almost a third of the horsemen were killed that day. Saddened by the memories, Vadek tried to shut them out, but deep down he knew one of his best friends was dead. In the still of the night, he knew he was not the only one to remember fallen comrades.

The icy wind was like a razor blade cutting into the very marrow of their bones which never failed to penetrate the prisoners’ worn, frayed clothes. Hands, numb in thin, tattered gloves, were unable to hold the tools required to position the iron nuts and bolts. They would then drop from stiff frozen fingers, resulting in a frenzied scramble to pick them up to escape being beaten senseless. Feet went black with frostbite caused by split worn boots, while eyebrows, hair, even eyelashes, turned white in the freezing air. The ice could seal eyelids shut and stick frozen fingers to metal. Bones and joints became as fragile as glass, so they broke under the slightest pressure. Yet no pain was felt as they awkwardly reset, without a person even knowing. Until much later.

A man could be clubbed to death for whispering to his neighbor. Except for the abuse and taunts from their guards, the long grueling day passed in silence.

Ana was dad’s girlfriend; they would have married.

Ana had come to say goodbye. The early morning cloud had turned into a fine drizzle as she walked the several miles to Kapice. She shivered, for her thin jacket did nothing to dispel the damp or provide any warmth. Her sandy hair seemed darker as it was plastered to her head, making her small features look even smaller. Russian soldiers had occupied her home also, and so she and her mother had decided to go to the town of Lumza, a four to five-day walk through the forest. Her mother’s sister lived there, and in the perhaps forlorn hope there would be some shelter there, they were leaving.

It was an emotional farewell. Camilla had grown very fond of Ana, and the feeling was mutual. She felt she was losing not only a dear friend and confidant but the daughter she had never had. Sheltering under a large and leafy tree, they talked for some time; of the war and the constant fear everyone felt and the loss of loved ones. And, of course, of Waclaw. For both, there had been no time to say goodbye to him, and there were many things left unsaid to the person they both loved. Each tried to console the other, and give reassurance they would meet again.

They clung to one another, each loath to let go, for who knew when they would see each other again. Then straightening up, Camilla and Ana faced one another, sorrow mirrored in their eyes. With a little smile, Ana turned away and slowly began to walk back the way she had come, the rain mingling with her tears.

“A Homeland Denied: In the Footsteps of a Polish POW ” by Irena Kossakowski is available on Amazon and in bookstores, published by Whittles, England in November 2016 and in America, April 2017.