The Germans were surprised at how many Russian POWs they had in such a short interval of time. Almost 3,000,000 people suddenly fell into their responsibility in just four months after Barbarossa. Like the Japanese and in fact just like the Russians, POWs were first captured, then they were marched on foot back to a labor camp. During Japan’s Bataan Death March, 17,000 men died at one rest stop.

It was in 1929 that the Geneva Convention at the League of Nations where international POW treatment standards were established. Prisoners were to be kept in surroundings and in care as comfortable as the guards. And no torture was allowed. Japan and Germany declined to sign the agreement. The United States did not death march its prisoners back during the war. No. Instead our Axis prisoners were treated to cigarettes and coffee and food and kept in decent clothes as we transported them back to the mainland United States where they were housed in almost 200 camps all across the country.

We took and kept 425,000 POWs during the course of the war.

The Japanese were particularly vicious and negligent with POWS. 16,000 Allied POWs died in Japanese custody and the rest were human skeletons. They probably killed 100,000 forced labor, particularly Chinese. Of the 50,000 British POWs 12,500 died in Japanese custody.

The Allied POWs were held in Germany, Italy, and Poland. Among US POWs were British, New Zealanders, Australians and Canadians.

POWs who weren’t mistreated suffered the harsh monotony of everyday life held in a small area and allowed to do things only permission was granted. For many it was broken up with Poker and Chess and Checkers.

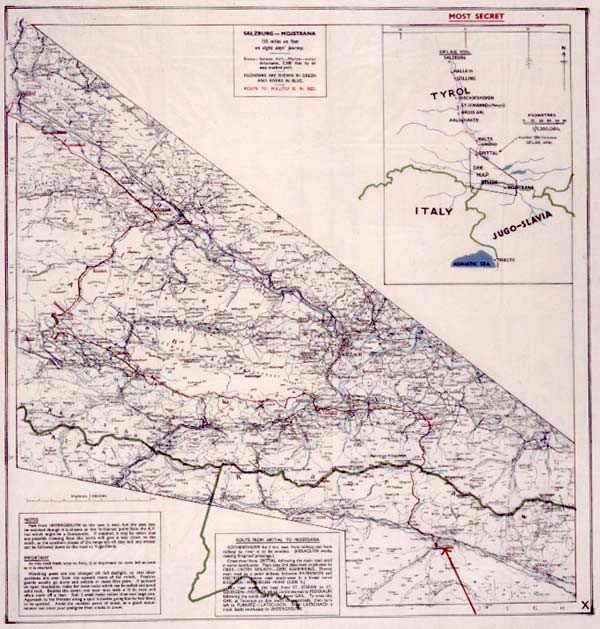

The Germans allowed Red Cross packages to be delivered to Allied POWs. Inside Monopoly boards were often found maps out of the camp. In fact, Monopoly boards with intelligence like faked travel documents had a red dot printed in the Free Parking space. Inside the clothing donated to POWs were maps sewn into silk inside the shirt. Letters home were filled with codes based on character placement in sentences. Corks, and lighters also had maps and coded messages loaded in them to inform prisoner how to egress. So the communication between Allied intelligence and POWs was quite robust.

Many Allied POWs knew which way to run because of the maps and data hidden in these care packages. Yes, Get Out Of Jail Free.

By J. Malcolm Garcia in Smithsonian Magazine wrote in 2009 about people who grew up and saw them:

About 12,000 POWs were held in camps in Nebraska. “They worked across the road from us, about 10 or 11 in 1943,” recalled Kelly Holthus, 76, of York, Nebraska. “They stacked hay. Worked in the sugar beet fields. Did any chores. There was such a shortage of labor.”

“A lot of them were stone masons,” said Keith Buss, 78, who lives in Kansas and remembers four POWs arriving at his family’s farm in 1943. “They built us a concrete garage. No level, just nail and string to line the building up. It’s still up today.”

Don Kerr, 86, delivered milk to a Kansas camp. “I talked to several of them,” he said. “I thought they were very nice.”

“At first there was a certain amount of apprehension,” said Tom Buecker, the curator of the Fort Robinson Museum, a branch of the Nebraska Historical Society. “People thought of the POWs as Nazis. But half of the prisoners had no inclination to sympathize with the Nazi Party.” Fewer than 10 percent were hard-core ideologues, he added.

Any such anxiety was short-lived at his house, if it existed at all, said Luetchens. His family was of German ancestry and his father spoke fluent German. “Having a chance to be shoulder-to-shoulder with [the prisoners], you got to know them,” Luetchens said. “They were people like us.”

“I had the impression the prisoners were happy to be out of the war,” Holthus said, and Kerr recalled that one prisoner “told me he liked it here because no one was shooting at him.”

Life in the camps was a vast improvement for many of the POWs who had grown up in “cold water flats” in Germany, according to former Fort Robinson, Nebraska, POW Hans Waecker, 88, who returned to the United States after the war and is now a retired physician in Georgetown, Maine. “Our treatment was excellent. Many POWs complained about being POWs — no girlfriends, no contact with family. But the food was excellent and clothing adequate.” Such diversions as sports, theater, chess games and books made life behind barbed wire a sort of “golden cage,” one prisoner remarked.

Farmers who contracted for POW workers usually provided meals for them and paid the U.S. government 45 cents an hour per laborer, which helped offset the millions of dollars needed to care for the prisoners. Even though a POW netted only 80 cents a day for himself, it provided him with pocket money to spend in the canteen. Officers were not required to work under the Geneva Convention accords, which also prohibited POWs from working in dangerous conditions or in tasks directly related to the war effort.