Frederick Mayer was a man described by some as fearless. He was a German Jew whose family emigrated from their home on the Western edge of the Black Forest in 1938 to make a new life in the United States. Mayer eventually headed back into Nazi-occupied territory in Europe – serving as U.S. spy.

Life as a spy was not short of action. Mayer parachuted onto an Alpine glacier, infiltrated enemy lines, and posed as a German officer to ascertain crucial intelligence. In 1945, after capture and torture by the Gestapo, he was responsible for accepting the surrender of a large German force.

Mr. Mayer died at his home in Charles Town, West Virginia, on April 15 this year. He was 94 years old. In an interview, Mr. Mayer stated that he had a “good combination of hatred and love: a hatred of the Nazis and a love for America.” His father fought valiantly in World War I, and Mayer had seen his family forced from their homeland by an evil regime that later murdered 6 million European Jews in the Holocaust.

Mayer was born in Freiburg, Germany, on Oct. 28, 1921. His family owned a hardware store that was boycotted because they were Jewish once Hitler became chancellor in 1933. His father didn’t want to leave Germany. With a military background, he thought his former service would protect his family from persecution. His mother, however, demanded that the family flee to the U.S. Young Fitz (Mayer’s nickname) was captivated by cowboy stories of the American West, and so looked forward to the journey.

After arriving in New York, Mayer changed his name to Frederick. He acted as the breadwinner while working as a mechanic at companies such as General Motors and Ford.

Once the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, Mayer enlisted in the U.S. Army. It was the perfect opportunity to kill Nazis, which was the reason many Jewish boys joined. Mayer’s superiors were impressed by his skill and native fluency in German and French, as well as English. They recommended him for the Office of Strategic Services, which later became the CIA. Mayer was assigned to the German Operational Group before heading out.

Historian K. O’Donnell published a volume called They Dared Return: The True Story of Jewish Spies Behind the Lines in Nazi Germany. He described these men: “A more eclectic group of desperados could not be found: former Luftwaffe pilots, Jewish escapees from German death camps, Polish deserters, world-class athletes, and even a former convict.” One recruit referred to the group as the craziest people he ever met.

At the start of 1945, Mayer was a highly trained agent for the Secret Intelligence division of the OSS and became the leader of the Operation Greenup. It was a mission focused on intelligence gathering in the area of Innsbruck. Allies suspected the Germans were plotting to make their final stand in the war there. On February 25, 1945, Mayer flew from his base in Italy and arrived in the Austrian mountains by parachuting with his team in the dead of night onto the ridge of a glacier.

John Billings, his command pilot on the mission, described Mayer as fearless about returning to Nazi Germany. It was hard to find a pilot to volunteer to fly in the difficult winter conditions over the glacier, but eventually, Billings stepped up, saying, “If they are crazy enough to jump there, I will be crazy enough to take them there.”

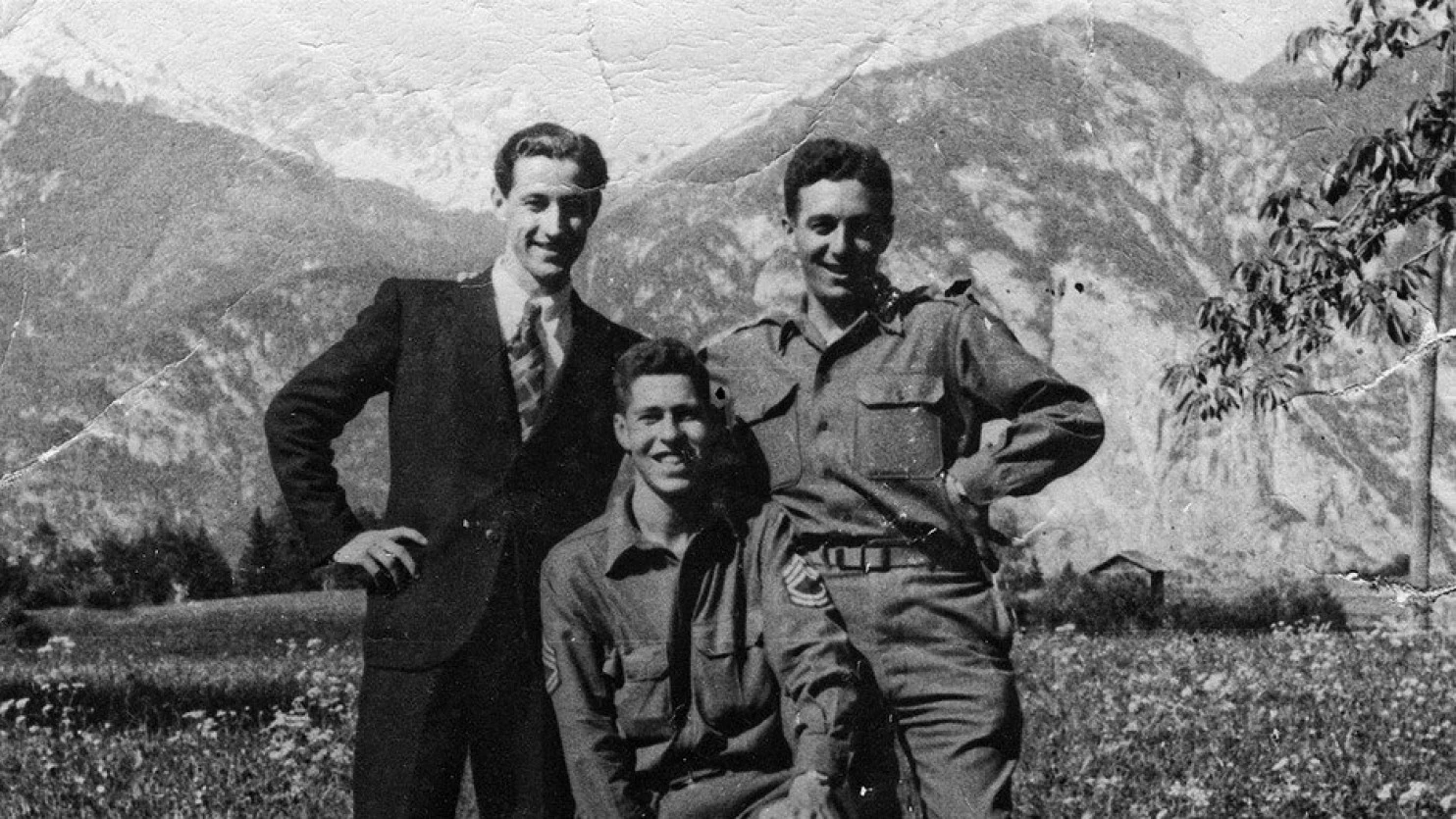

Hans Wynberg, a Dutch-born Jew whose family was sent to Auschwitz, and Franz Weber, an Austrian officer who had defected from the German army, worked with Mayer. The trio had supplies packages dropped with them, but unfortunately were unable to locate the packet containing their skis. They had to walk down the glacier, sometimes waist deep in snow.

They eventually made contact with Weber’s family. Weber’s sister was a nurse who helped Mayer disguise himself as a German officer in uniform and bandaged up from a head wound. Then he posed as a French electrician to infiltrate a Messerschmitt factory. His undercover work led to valuable intelligence and a network of informants that helped identify the location and dimensions of Hitler’s Führerbunker in Berlin, the condition of Nazi war plants and movement of enemy freight and troops through the Brenner Pass.

However, things took a turn for the worse when a member of Mayer’s spy network betrayed him. He was imprisoned and tortured. His captors whipped him, doused him with water and suspended him from a rifle, but he only admitted he was an American officer when the man who had betrayed him was brought in and identified him. His torturers wanted to know the location of his radio operator, but Mayer insisted that he worked alone.

The German officer in charge was one Franz Hofer. Hofer, convinced that the war was a lost cause, was looking for a way to surrender to the Americans rather than to the Soviets. When he realised for certain that his prisoner was an American officer, he had Mayer cleaned up, dressed, and fed. In fact, Mayer was taken to Hofer’s home, met Hofer’s wife, and ate with them. During these discussions, it was agreed that the Germans under Hofer should surrender to Mayer, as the representative of the US military.

Tom Moon, author of This Grim and Savage Game: OSS and the Beginning of U.S. Covert Operations in World War II, wrote, “The Germany Army in that area had in effect surrendered to an OSS Jewish Sergeant.”

Mr. Mayer was recommended for a medal of honor in 1945 by a superior officer. In the nomination was written, “In constant danger of his life, he exhibited almost unbelievable courage, resourcefulness and enterprise.” Mayer received the Legion of Merit and the purple heart, among a number of other awards.