Everyone loves a good secret, more than a dash of intrigue, and stories of unlikely heroes – like the story of a band of artists, engineers, actors, meteorologists, sound technicians, and architects that were pivotal in the Allied force’s success during WWII.

The 23rd Headquarters Special Troops of the United States Army known as The Ghost Army was a unit created to deceive enemy soldiers. They succeeded with the use of fake tanks, recordings of battle sounds, dummy fighter planes and more.

The idea for the Ghost Army was at the time taken from the British, who had successfully used a deception unit in Egypt. This deception, called Operation Bertram, was the brainchild of Dudley Clarke who had made it his mission to bait and switch Erwin Rommel. One story goes that actor Douglas Fairbanks Jr. knew of these deceptions and, as a Naval Reserve soldier and friend of FDR, lobbied the armed forces to implement a similar program.

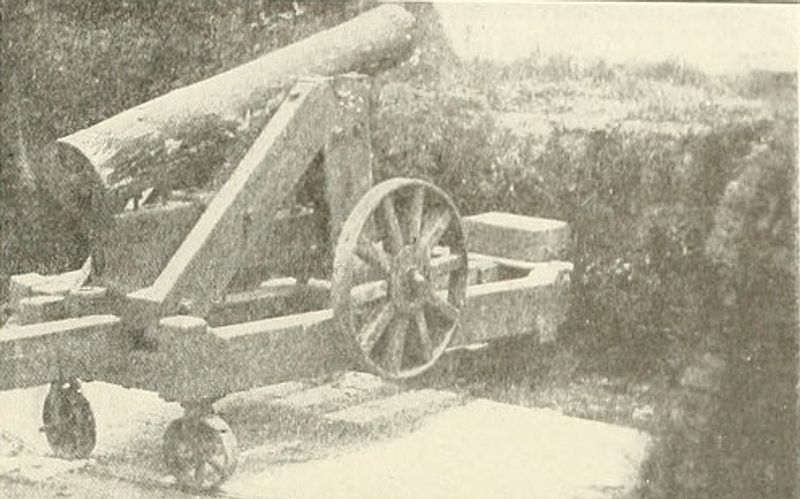

Even though the recent inspiration was the British, the tactic goes back in its simplest form to the American Revolution. General Washington, in an attempt to encourage the surrender of Loyalist Colonel Rowland Rugeley, used a pine log to create a fake cannon. Rugeley believed Washington’s artillery to be real and gave up the fight.

During the U.S. Civil War, the Confederates used the same idea with what were called “Quaker Guns” – logs painted to look like cannons, to deceive the Union troops into believing they were better equipped and in larger numbers than they actually were.

The deception efforts of WWII were much more sophisticated than the simple Quaker Gun, however.

The Ghost Army was not formed to take inflexible orders. They were given missions and allowed to use their creativity to accomplish tasks. That’s why and how these troops were chosen. The Army wanted the best and the brightest from every point on the creative spectrum to collaborate and plan the most deceptive illusions.

They were recruited from the very cornerstones of creativity from art, design, and engineering schools to the upper echelons of the creative world. Ghost Army soldiers included the famous and the yet to be famous such as Bill Blass, Douglas Fairbanks Jr., Art Kane, George Diestel, Arthur Singer, and Ellsworth Kelly – to name only a few of the 1100 soldiers who served in this strange and fascinating capacity.

The Ghost Army’s movements included more than a mere “tank” or two placed at key points. These operations were full-blown theatrical productions. Utilizing 500-pound speakers, inflatable tanks, pyrotechnics, and sonic deception, they were able to mimic the assembling of existing units. They did this with minimal camouflage because the purpose was to draw attention away from actual forces.

The Ghost Army was not immune to danger, in fact, they were meant to draw it. They served on the front lines, often as the front line, with no real means of defense. They played decoy at significant risk.

While a lot of operations involved the visual, many were merely auditory. Radio broadcasts were made to fool listening Germans, and loudspeakers were used that blasted the sounds of tanks and troops on the move.

Sometimes the 23rd would create the illusion of a big battalion in transit by driving their trucks over and over again through the same village, circling it. For each pass they would change their shoulder insignias and redraw the symbols on the vehicle in chalk.

It wasn’t all bad, though. Some missions were almost, if not actually, enjoyable. Soldiers were sometimes assigned to go into towns to drop misinformation. On these visits they were told to have fun, meet girls, and enjoy themselves while pretending to be parts of a unit they were attempting to decoy. This also allowed them to play up parts that advanced their rank with colonels playing the roles of generals and so on. They’d act as though they were drunk and let “slip” what seemed to be crucial information.

Fortitudes

In order to keep the Germans thinking the invasion would take place anywhere but in Normandy, two big deception operations were run; Fortitude North and Fortitude South.

Fortitude North was designed to mislead the Germans into expecting an invasion of Norway. By threatening any weakened Norwegian defence, the Allies hoped to prevent or delay reinforcement of France following the Normandy invasion. The plan involved simulating a buildup of forces in northern England and political contact with Sweden.

During a similar operation in 1943, Operation Cockade, a fictional field army (British Fourth Army) had been created, headquartered in Edinburgh Castle. It was decided to continue to use the same force during Fortitude. Unlike its Southern counterpart the deception relied primarily on “Special Means” and fake radio traffic, since it was judged unlikely that German reconnaissance planes could reach Scotland without being intercepted.

False information about the arrival of troops in the area was reported by double agents Mutt and Jeff, who had surrendered following their 1941 landing in the Moray Firth. Fortitude North was so successful that by late spring 1944, Hitler had thirteen army divisions in Norway

Fortitude South employed similar deception in the south of England, threatening an invasion at Pas de Calais by the fictional 1st U.S. Army Group (FUSAG). France was the crux of the Bodyguard plan; as the most logical choice for an invasion the Allied high command had to mislead the German defences in a very small geographical area.

The Pas de Calais offered some advantages over the chosen invasion site, such as the shortest crossing of the English Channel and the quickest route into Germany. As a result, German command, particularly Rommel, took steps to heavily fortify that area of coastline. The Allies decided to amplify this belief of a Calais landing.

Montgomery, commanding the Allied landing forces, knew that the crucial aspect of any invasion was the ability to enlarge a beachhead into a full front. He also had only limited divisions at his command, 37 compared to around 60 German formations.

Fortitude South’s main aims were to give the impression of a much larger invasion force (the FUSAG) in the South-East of England, to achieve tactical surprise in the Normandy landings and, once the invasion had occurred, to mislead the Germans into thinking it a diversionary tactic with Calais the real objective.

Crossing The Rhine, Sort Off

The most extensive of their 20 operations was the use of every trick in their playbook at the crossing of the Rhine. To lure the Germans away from the real action, they created the illusion of the 30th and 79th divisions – over 30,000 men plus artillery and vehicles – crossing at Viersen, all with only 1100 men, some fake planes, and a few real tanks mixed in with the inflatable ones.

The operation hit its target. The Germans were fooled and lured to the wrong location leaving only a disorganized front at the location of the real crossing. This operation saved many American lives as a result.

The Ghost Army was a major point of success in the war, affecting the surrender of large German units to their 1100 man operation, and the estimated figure of 15-30,000 G.I. lives that would have been sacrificed had it not been for the 23rd’s existence.

The U.S. government kept the 23rd a secret for many years. The soldiers were never able to tell a soul the great stories they had of the war and their many accomplishments. It wasn’t until the Freedom of Information Act that these stories began to be discovered. Many of the operations of the Ghost Army are still classified.

Sources:

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Quaker_Gun

- http://nasaa-home.org/23rdhqs.htm

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Bertram

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ghost_Army

- http://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/when-an-army-of-artists-fooled-hitler-71563360

- https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Operation_Fortitude

- http://blog.seattlepi.com/bookpatrol/2010/03/12/ghost-army-haunts-michigan-library/

- http://www.ghostarmy.org/bio/f/The_Mission/412