In the annals of history, there are events that stand out not for their grandeur or significance, but for their sheer absurdity. One such event is the infamous Emu War – also known as the Great Emu War – that unfolded in Australia between November 2 and December 10, 1932. Often regarded as a quirky episode in military history, the conflict serves as a reminder that even the most advanced weaponry can be bested by determined and resourceful opponents – in this case, a horde of flightless birds.

Origins of the Emu War

Following the First World War, soldiers returning home were given land in Western Australia by the government. When the Great Depression occurred, the government encouraged these farmers to grow as much wheat as possible. It offered subsidies to assist, but never actually came through with that promise. As a result, the price of wheat plummeted.

By October 1932, the situation had turned from bad to absurd. Migrating after the breeding season, 20,000 emus arrived in Western Australia. The large, flightless birds settled in the farmland, eating and destroying crops. They also damaged fences, leading other animals to enter these properties and cause even more issues.

Looking for assistance

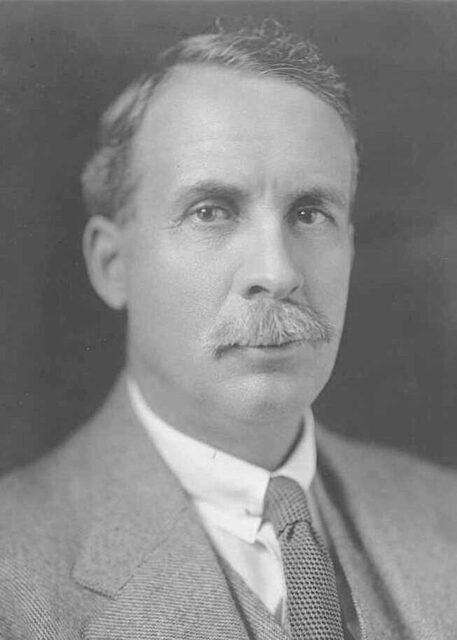

Facing the possible destruction of their livelihoods, these soldier-settlers turned to Sir George Pearce, the Australian Minister of Defence. They requested machine guns, having witnessed their effectiveness during the Great War. Pearce agreed, but under one condition: the farmers would have to pay for the ammunition used, as well as feed and put up the men tasked with manning the weapons.

Assisting the farmers was important, although Pearce had approved the idea partially because the emus would make good targets for the Australian soldiers to practice on.

Rainy weather delays the start of the Emu War

The war on the emu population was set to begin in October 1932. Maj. Gwynydd Purves Wynne-Aubrey Meredith of the Royal Australian Artillery’s 7th Heavy Artillery commanded Sgt. S. McMurray and Gunner J. O’Halloran, who were armed with two Lewis guns and 10,000 rounds of ammunition.

The start of the offensive was delayed due to a period of rain, which saw the emus spread out over a larger swath of land. The rain stopped on November 2, and the soldiers prepared to take on their feathered foes. Their orders were, as reported in a newspaper from the time, not only to assist the farmers, but to collect 100 emu skins. This was so their feathers could be used on the hats of the Australian Light Horse.

Launching the Emu War

On November 2, 1932, the Australian soldiers encountered about 50 emus at Campion. They opened fire, but the birds were out of range. The farmers then herded the animals into an ambush, which resulted in some of the emus being killed. Later that day, it was reported that “perhaps a dozen” had been slain in a second attack.

The next engagement occurred two days later, when the troops encountered about 1,000 emus. They opened fire, killing 12, but their machine gun jammed and the rest scattered.

By November 8, 2,500 rounds of ammunition had been spent while the amount of emus killed was estimated to be between 50 and either 200 or 500 – the latter number was provided by the farmers.

One of history’s strangest conflicts

The Australian military withdrew on November 8, 1932, citing negative media attention and the lack of success. That being said, the emu population continued to be a problem. After the farmers, again, asked for help, the operation resumed on November 13. This time around, the soldiers saw more success, killing around 100 emus every week.

On December 10, Maj. Gwynydd Purves Wynne-Aubrey Meredith submitted a report, stating that 986 emus had been slain and that the soldiers had used 9,860 rounds of ammunition – about 10 rounds per emu. He also reported that 2,500 birds had been wounded and died from their injuries.

More from us: Michael Caine Became a Staple of the War Movie Genre With These Releases

While the conflict lasted just over a month, it still remains one of history’s oddest wars, when agile birds defeated machine guns.