Recent events have shown that whatever fate throws at Paris, the old city somehow manages to sort itself and get on with things. In truth, this is pretty much the case with just about anywhere, but there is something about the City of Light that draws people from all over the world, and very few cities can boast such a reputation.

I have been in Paris a few times, the first in 1967 and the last fifteen years ago. I did a schools exchange to Suresnes, a suburb of the city, in 1975 when I was a spotty fifteen-year-old. Being London kids some of us sneaked under a fence into the fort at Mont Valerien and watched a group of soldiers throwing dummy hand grenades in the moat before we were invited to scram. I doubt we’d get away with that now! I have very fond memories of that trip and for the family, I stayed with. I still have a Ville de Suresnes t-shirt the mayor gave me somewhere in my house.

Mont Valerien was a dark place during the war, the scene of hundreds of executions of Resistance members and it was this sort of oppression that helped draw Charles de Gaulle to his vehement stance that the Liberation of Paris should be achieved at the hands of the city, itself, and not by a foreign army. William Mortimer Moore tells the story of the Liberation in this fascinating and entertaining book.

The state of French politics in 1944 was a quagmire of factions and ideals that continued from the malaise before the war when there was little stability in the country. Fear of fascists, fear of communists, fear of a new Commune; fear of fear itself – it was all on the table. Loathing for Pierre Laval and his Vichy supporters was matched by the concern of a communist take over. France was a divided country in so many ways and even within the ranks of the Free French, the only thing most people could agree on was getting rid of the Germans.

Charles de Gaulle had a vision of France renewing itself through Liberation. He hated having to go cap in hand to the ‘les Anglo-Saxons’, and he demanded that he was seen as the legitimate voice of the country within the Alliance. But Roosevelt loathed him and took issue with his democratic credentials. Would De Gaulle impose a new dictatorship on a liberated France? Churchill was more pragmatic. Although the two men were never chums, he saw de Gaulle as the only realistic option, and he believed that a strong rebuilt France was essential to the world order. His fear of communism made de Gaulle, the ideal person to work with. For de Gaulle the agony of seeing his country occupied and ruined by the Germans did not distract him from an empirical belief that only France could heal itself, and he was the man to lead the way.

The role of Philippe Leclerc and his 2nd Armoured Division forms the spine of this story, and it is a glorious one to read. The division was such a mixed band of brothers from so many backgrounds and nationalities, but, for me, the Spaniards dominate. As an aside it is important to remember the exiles from Spain who fought for France. I have visited the graves of several who died in defence of the country in 1940, so it is fantastic to read of their comrades who saw victory in 1944 and 1945. The 2e DB was a very unit and under Leclerc it performed magnificently. But even here there were sensitivities with men who had made the march across the desert from Chad taking issue with others who had come over to the cause after the Allied victory in France’s North African colonies. Leclerc had to manage all this while leading a division in battle. We read so much about the rivalries within the Anglo-American alliance, but the story of victory in Europe is so much richer than just yanks and limeys.

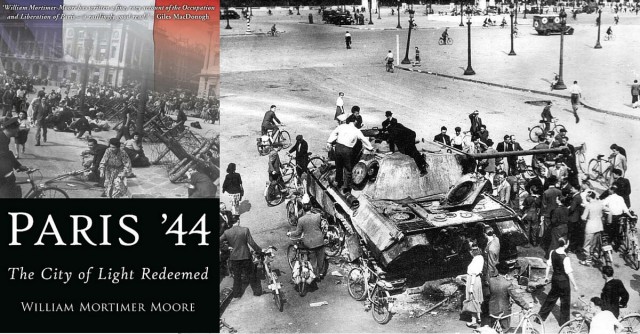

Charles de Gaulle wanted Paris to free itself and the uprising against the Germans proved to be a dramatic and sometimes tragic affair. History tells us that the commander of the city, Dietrich von Choltitz, did not want to destroy the city as Hitler had ordered and he always claimed credit for saving Paris. Mr Mortimer Moore shows there was a lot more to the story than just one benevolent general. In fact, the saga is a bit of a labyrinth, but the author unravels it all with great style and makes it easy to follow.

Choltitz had his difficulties; he was implicated in war crimes on the Eastern Front and he was too close for comfort to the July 20th plotters. He trod a difficult path. Up steps one of the great heroes of the war, Swedish diplomat Raoul Nordling. Perhaps if anyone should have the mantle of saviour of Paris, it is him who has a serious claim. Nordling worked wonders to bring Choltitz round to freeing prisoners and letting the city go. But it was no easy task and Nordling’s role is essential to this story.

The drama of the Liberation has all the ingredients a good story needs – heroism, guile, tragedy, betrayal, and varying degrees of fortune. I found all the characters to be absorbing – much worthy of intense admiration and respect. But for all the heroes there have to be some opposite numbers, and we see the Nazis at their cynical worst. They were executing people at Mont Valerien right up until the last minute and putting others on trains heading to their certain doom.

The desperate supporters of Vichy, the Milice and all the collabos seem pathetic from this distance, but such was the mess of French politics that it all seems so needlessly complicated from the relative safety of 2015. In the end, you may have to ask if you have any sympathy with Philippe Petain. You should not have any for Pierre Laval. There were many other nasty individuals knocking about doing the Germans work for them, and many of them met the firing squad and could have no complaints.

A kaleidoscope of colour is added by Pablo Picasso, a piratical Ernest Hemingway and the photography of Henri Cartier-Bresson and Robert Capa. After all, this is France! This book arrived without notice from the publisher, and I am so glad. I have been lucky to read some wonderful books this year and right at the end Mr Mortimer Moore’s masterpiece landed on my doormat.

This one definitely gets the full five stars. I am reminded of some of the classics I read years ago – a style of writing that has faded a little in modern times. This book follows on beautifully from the works of those by Alistair Horne and while I am far from an expert on the subject the prose here really does bring wartime France to life. This is a very important book, and if you want to achieve a deeper understanding of the bigger picture of the liberation of Europe, then you really must read it.

Charles de Gaulle never forgot (or perhaps forgave) Churchill for telling him Britain would always look to the United States. When the time came, he was content to veto Britain’s membership of the former European Economic Community, and I wonder what he would think now of us having a referendum on our continued membership of the current European Union. Charles de Gaulle is a difficult figure for reasons well known. His legacy is divisive in France, where politics has never been anything less than passionate. But his vision of saving France and building a new Republic defines him. His determination ensured we will always have Paris.

Reviewed by Mark Barnes for War History Online

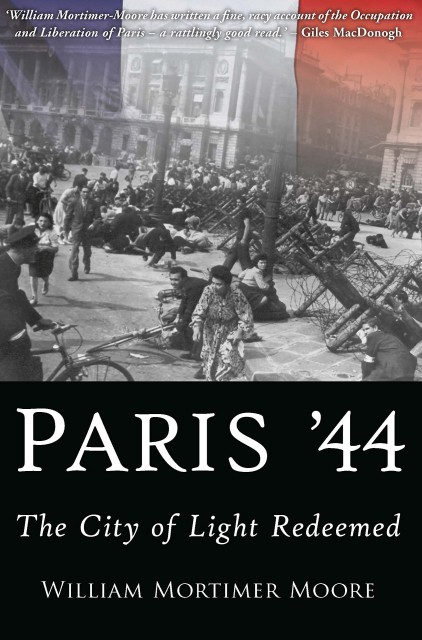

PARIS ‘44

By William Mortimer Moore

Casemate

ISBN: 978 1 61200 343 6