Between 1948 and 1960, a guerrilla insurgency tore Malaya apart. Communist rebels fought against British and Commonwealth troops as well as local military forces and the police. It was a conflict that has often been contrasted with the Communist offensives in Korea and Vietnam. It was also the conflict which produced the idea of victory by winning “hearts and minds.”

Origins of the Conflict

From the mid-18th century, the British took control of increasingly large areas of the Malay Peninsula. Like many parts of the British Empire, it produced valuable resources for the British, who dominated politically, economically, and socially.

During WWII, British Malaya was occupied by the Japanese. In the aftermath of Japan’s defeat, the British returned to dominance, and the Malays relied on them to rebuild.

The Malayan economy, heavily dependent on exports of tin and rubber, struggled to recover. From 1946 to 1948, trade unions sought a better deal for Malay workers, amid rising tensions between locals, Chinese immigrants, and the British governing class. As the British took increasingly harsh measures against the unions, support grew for the cause of Communism.

A War that was Not

The conflict which broke out in 1948 was referred to by the rebels as the Anti-British National Liberation War. However, the British refused to refer to it as a war at all.

Lloyds of London insured Malaya’s rubber and tin manufacturers. Their insurers would not pay out for losses incurred as a result of a war. For that reason and other public image purposes, the British authorities downplayed the conflict. They labeled it as the Malayan Emergency.

Violence Begins

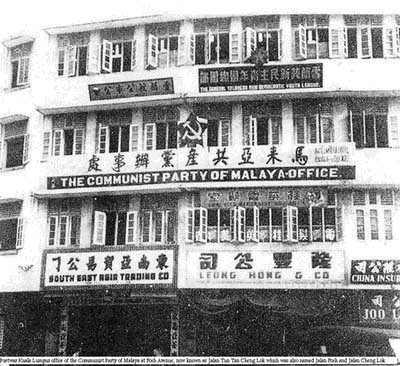

On June 16, 1948, the rebels killed three European planters. In response, the British brought in emergency measures, and the Malayan Communist Party (MCP) was outlawed.

The MCP went into hiding in remote rural areas. They founded the MNLA, the Malayan National Liberation Army. It was initially mainly made up of guerrilla veterans who had fought against the Japanese. As in Korea and Vietnam, Western forces faced men they had trained and supplied during a previous war.

The MNLA’s Campaign

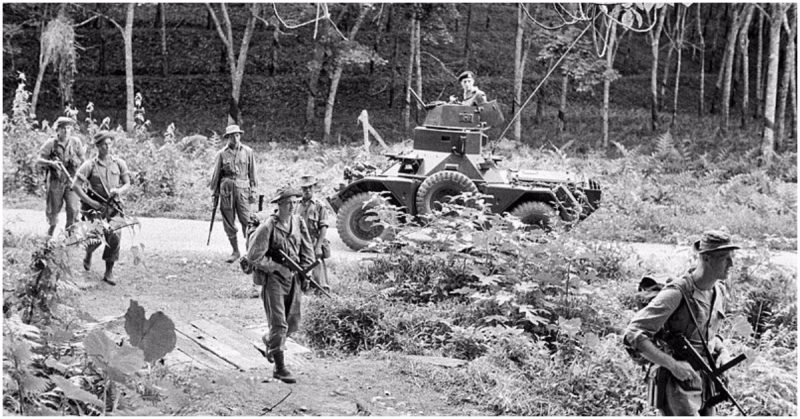

The MNLA fought a guerilla campaign against the authorities, using sabotage and ambushes to make the most of their irregular and poorly equipped troops.

For support, they relied upon the Chinese population. Lacking land and voting rights, and often much poorer than other Malays, the Chinese were natural supporters of the communists. Some Malays also helped them.

As the war progressed, the MNLA tried to tighten its hold by using intimidation to keep farmers and planters in line. It was a tactic that did as much to alienate their support base as to bolster it.

The British Response

The initial British response was the conventional one taken by an imperial power facing irregular opposition. Organizations were banned, their supporters were hunted down, and those suspected of helping the communists were publicly punished. Broad military sweeps were sent into the jungle to seek out and destroy the rebels. Troops sometimes crossed the moral and criminal line, resulting in torture, mutilations, and at least one massacre.

Air power was brought in, with heavy bombing and the use of herbicides to defoliate areas where rebels might be hiding.

The Briggs Plan

In 1950, Sir Harold Briggs became Director of Operations for the efforts to tackle the emergency. He developed the Briggs Plan.

The aim of the plan was to undermine support for the MNLA which came primarily from the ethnic Chinese population. They were forced to resettle in new villages, away from the communist controlled areas. Collective punishment was sometimes used against them.

Along with the stick came the carrot. Some social and health care was provided, to create a positive reason for people to support the British against the rebels.

Gurney’s Assassination

On October 6, 1951, the MNLA killed the British High Commissioner, Sir Henry Gurney. Although the assassination was successful, its effect was not everything the MNLA might have wanted. It hammered home the fact that no-one was safe from the conflict, contributing to the desire for peace. It brought in the man most credited with ending the conflict – Gurney’s successor, Lieutenant General Gerald Templer.

Templer Takes Charge

Over the next two years, Templer built on the policies brought in by Briggs. He developed a campaign firmly focused on shifting support away from the guerillas, winning over hearts and minds. The MNLA’s support base was stripped away. Patrols by British and Commonwealth troops became more focused and disciplined.

The number of rebel attacks and casualties on the British side dropped by 80%.

Amnesty

In September 1955, the Malayan government offered an amnesty to the rebels.

It did not lead to widespread surrenders. The terms were not generous enough to win many rebels round, and communist propaganda against it was effective.

The amnesty was still a turning point. Widespread demonstrations in support of the amnesty showed that people wanted peace. The possibility of talks had been opened up. The political landscape was fracturing.

Popular parties emerged at the ballot box, seeking peaceful independence and better care for ordinary Malays. It was no longer a conflict between Britain and the communists.

A Creeping Peace

Peace talks began but did not get far. Operations were increased against the MNLA.

In 1957, Malaya was given its independence. The communist insurrection could no longer label itself as a war of independence against a colonial government. The MNLA was fighting against an independently elected government.

Bit by bit, the rebels were worn away. The last serious resistance was defeated in 1958. Some rebels surrendered, others fled the country.

In 1960, the government declared the emergency at an end. By focusing on undermining the rebel support base, the British and then the independent Malays defeated the communist insurgency.

They had won over hearts and minds.