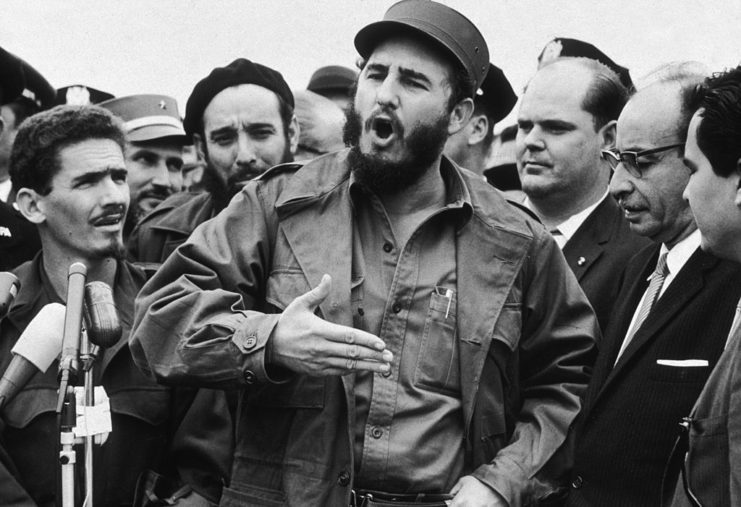

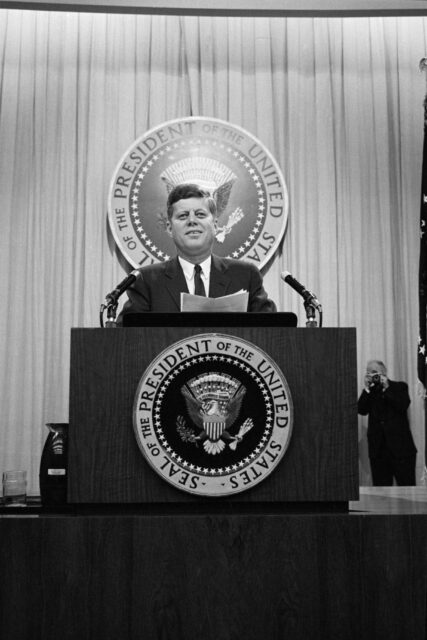

In 1961, during the disastrous Bay of Pigs Invasion, the U.S. covertly enlisted Alabama Air National Guard pilots to fly support missions for the CIA’s attempt to topple Fidel Castro. Publicly, Washington denied that American service members had any role, determined to preserve plausible deniability.

When the operation collapsed within days, critics blasted its poor planning and flawed execution, placing much of the blame on the CIA. The fallout worsened when Cuban forces recovered and identified the body of Lt. Thomas “Pete” Ray, an American pilot shot down in combat. Even then, U.S. officials refused to admit his involvement or repatriate his remains.

That refusal only deepened public distrust, transforming the Bay of Pigs from a military failure into one of the most politically costly covert actions in American history.

Bay of Pigs Invasion

To conceal American involvement, the military took elaborate steps, such as repainting U.S. aircraft with Cuban markings to mimic defection or internal rebellion. The CIA and U.S. military had trained both the exile fighters and the pilots set to fly Douglas B-26 Invaders—twin-engine bombers similar to those already used by Cuba’s air force, which helped maintain the illusion.

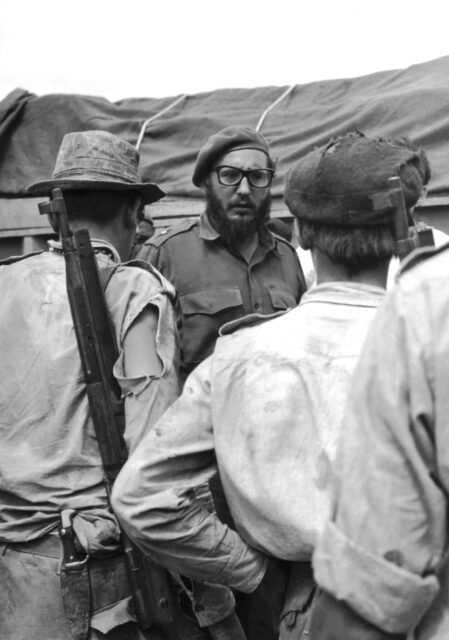

By then, the B-26s were outdated, no longer in frontline service, and the only remaining units were operated by the Alabama Air National Guard. While these guardsmen were tapped to train exile pilots and maintain the aircraft, they were given strict orders not to fly combat missions themselves. But as the invasion unraveled, that boundary was crossed—with deadly consequences.

Lt. Thomas “Pete” Ray was shot down

Lt. Thomas Ray of the Alabama Air National Guard was shot down while piloting a B-26 Invader during the Bay of Pigs Invasion. His plane was hit by Cuban anti-aircraft fire shortly after attacking Fidel Castro‘s field headquarters. In similar operations, napalm was dropped on the intended targets below.

Although U.S. pilots were initially prohibited from participating in the invasion, the CIA reluctantly gave their approval as the situation grew more desperate.

The Los Angeles Times reported that the agency emphasized the importance of secrecy to the airmen: “Cannot attach sufficient importance to fact that American crews must not fall into enemy hands. In the event this happens, despite all precautions, crews must state [they are] hired mercenaries, fighting communism, etc.; U.S. will deny any knowledge.”

The CIA continued to deny their involvement

Lt. Thomas “Pete” Ray’s body is returned to the United States

If the CIA had tried to bring Thomas Ray’s body home, it would have meant publicly admitting that American forces were directly involved in the Bay of Pigs Invasion. This was something the government wanted to avoid at all costs. Even Cuban officials were puzzled by how coldly the U.S. seemed to treat one of its own fallen soldiers.

After Ray went missing, his wife began pushing for answers. But those tied to the Alabama Air National Guard kept quiet, likely under pressure. Over the years, several disturbing rumors have surfaced about how the CIA handled the situation. One report, mentioned in the Los Angeles Times, claimed that agency officials even threatened to have Ray’s wife institutionalized if she didn’t stop digging into what really happened.

Ray’s daughter tried to recover his body

In 1979, Cuba became aware that Ray’s daughter, Janet Ray Weininger, was trying to recover her father’s body. As a result, his body was returned to the US. It was also around this time that the CIA privately informed Weininger that Ray had participated in the Bay of Pigs Invasion and had actually been awarded the agency’s highest award: the Distinguished Intelligence Cross.

Despite Thomas Ray’s body having been returned and Weininger receiving her much-sought after answers, the CIA still refused to publicly confirm the airman’s involvement in the Bay of Pigs Invasion until 1998, when additional media pressure was applied. In addition to this, it was revealed the agency had also set up a fake company to pay the families of the deceased pilots a regular sum of money, and even funded their children’s post-secondary education.

As this information was finally public knowledge, Ray’s name was finally added to the Book of Honor in the foyer of the CIA’s headquarters.