During the height of the Cold War, the U.S. Army launched Project Iceworm, a secret initiative to build a network of nuclear missile sites beneath Greenland’s massive ice sheet. The concept depended on the ice’s sheer thickness to hide warheads positioned close enough to strike the Soviet Union—yet the constantly shifting glaciers made the plan nearly impossible to execute.

To test the feasibility of this idea, the Army constructed Camp Century in 1959, an underground complex complete with living quarters, laboratories, and even a portable nuclear reactor. Over time, however, the movement of the ice began to crush, twist, and destabilize the tunnels, creating increasingly hazardous conditions for both personnel and equipment. By the mid-1960s, the Army recognized the plan’s fatal flaws, and in 1967, Camp Century was abandoned, quietly marking the end of Project Iceworm.

Getting permission from Denmark

In 1951, the United States and Denmark entered into the Defense of Greenland agreement, permitting NATO allies to explore the establishment of military installations on the island to protect Greenland and other NATO territories. This pact essentially authorized the U.S. to build a base there.

However, the agreement did not extend to deploying nuclear missiles on Greenland. Danish Prime Minister H.C. Hansen cautioned against introducing nuclear arms, aiming to prevent escalating international tensions. Yet, when U.S. Ambassador Val Petersen questioned Hansen about the Army’s plans, the prime minister refrained from outright denial, leaving room for the project to move forward.

Officially, the U.S. Department of Defense framed the initiative as a way to test Arctic construction methods, trial portable nuclear reactors, and carry out scientific research on the ice cap. The true goal—positioning nuclear missiles—was notably omitted from the public explanation.

Camp Century

The Army named the project “Camp Century,” using it as a public disguise for the true nature of the operation.

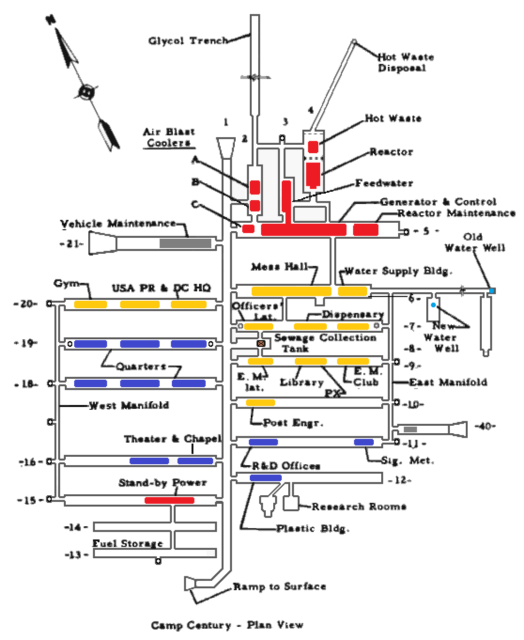

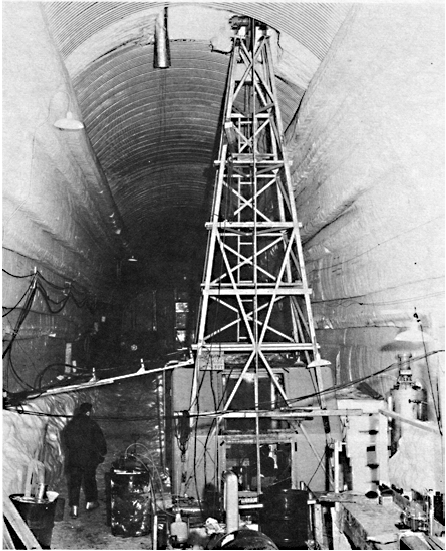

Construction began in June 1959 and was completed just over a year later, in October 1960. The process was challenging. A three-mile-long access road was built to transport equipment and supplies to the location. Trenches were dug into the ice, reinforced with steel arches to create a roof, and then covered with snow for additional protection and concealment.

Within these trenches, wooden buildings were put up, with gaps left between the walls and the ice to minimize melting caused by internal heat. The base was insulated, sourced fresh water from the ice, and was powered by the world’s first portable nuclear reactor (the PM-2A), which was installed in 1960.

Camp Century was capable of housing over 200 soldiers and included various amenities, such as a kitchen, cafeteria, laundry, communications center, hospital, chapel, and even a barbershop. It featured 26 tunnels and acted as a testing ground for assessing the viability of operations beneath the ice.

Project Iceworm

Camp Century was really just a cover story for the Army’s top-secret project called Iceworm. Inspired by Camp Century’s layout, Project Iceworm aimed to build a massive network of underground tunnels stretching over 52,000 square miles—an area about three times the size of Denmark.

Within this huge tunnel system, the U.S. planned to deploy 600 “Iceman” ballistic missiles, each placed four miles apart. The project also included plans for 60 Launch Control Centers to manage the missile network. The goal was to bury these weapons deep under Greenland’s ice sheet, giving the U.S. a hidden advantage for launching strikes—mainly aimed at the Soviet Union during the Cold War.

The Iceman missile was a modified version of the Minuteman Intercontinental Ballistic Missile (ICBM) and could hit targets up to 3,300 miles away. To keep the whole operation running, the Army expected to house around 11,000 troops at the site.

Problems with Project Iceworm

Campy Century could have a long-lasting ecological impact

Project Iceworm remained a secret until the Danish Institute of International Affairs began investigating the former military base. Documents about the Army’s true intentions were declassified in 1996, and the secret about Camp Century was finally revealed to the public.

Years after the base was shuttered, its tunnels collapsed, and now a thick layer of ice covers the once-operational facility, making it virtually unreachable. However, the operation wasn’t for nothing, as Camp Century actually provided valuable information via the collection of some of the world’s first ice core samples.

The environmental effects of Project Iceworm may be awaiting society in the future. While Camp Century was in operation, its nuclear reactor produced over 47,000 gallons of radioactive waste that’s still buried under Greenland’s ice cap.

More from us: How Many Times Did the World Nearly End During the Cold War? Answer: A Lot

Scientists believe that, if climate change continues at the rate it currently is, the ice cap could melt enough to expose the nuclear waste by 2100, which could negatively impact the ecosystems within the surrounding area.