One of the best things about running this blog and the connected twitter account is that they bring me in touch with good and interesting people all over world. One such accquaintance is Thorsten Herbes, a german compatriot living in the USA. He has written a story about his grandfathers experiences in WW2 and not only did he do a wonderful job with the research, its also obvious how much he misses his grandfather (german: Opa). I am honored and very happy that he allowed me to share this story and I am sure you will find it as excellent as I did.

Thorstens Grandfather served with Infanterie-Regiment 545 in Stalingrad and was one of the few who got out, being evacuated via Gumrak inside a Heinkel He-111. I do not want to imagine what he must have experienced there. The name of Gumrak alone sends shivers down my spine, but this may be part of a later story. Time for Thomas and his Opa (Grandfather) to take over.

Foreword

For as long as I can remember, I have been fascinated by the Second World War. When I was old enough to realize that he had been a participant, I began to beg my grandfather to tell me stories about the war, often to the dismay of the rest of the family, who’d grown tired of hearing them. I was mesmerized by his descriptions of Russia and awestruck when he showed me his surviving pieces of equipment. Never before had history felt so real, so touchable. I remember playing with his bayonet and searching every drawer in his house, hoping to find another hidden treasure.

As I got older, I began to look at history from a larger perspective, learning about the cause of war, the strategy and the equipment. I built a small library of books and devoured them at every opportunity. I visited every military museum I could find and often dragged many an unwilling participant along with me. Although my fascination with the technology and tactics of war never faded, an additional question began to form in my head – how did the experience of war affect a human being? What did the veterans experience on a personal level and how did it influence my grandfather?

When I left Germany in 1992 to move to the United States, I lost the ability to visit Opa and Oma as often as I’d been used to and our conversations and meetings became more infrequent and precious. The more time passed, the more I realized that we were losing members of the World War II generation daily and with them the personal connection to their past. I took every opportunity I could to preserve Opa’s history, taping conversations and taking notes. During a trip to Germany in the fall of 2008, sitting at his kitchen table, listening to his stories, I realized that the end of Opa’s military experience occurred during the Battle of the Bulge in Luxembourg, no more that 2 hours’ drive away from his home – but that he’d never been back after the war. The following day, my wife and I drove to Luxembourg to explore some of the sites Opa had mentioned and to take some pictures for him. We found villages like Bastendorf and Diekirch, where my wife convinced me to stop at the military museum. At first I didn’t want to make her spend a day of our honeymoon looking at tanks, but she was insistent. The museum was amazing and brought back that feeling I had as a kid, when history was real and touchable. I wondered if any of the thousands of artifacts belonged to Opa and was almost expecting to see his picture hanging on the wall at every turn. It was at the museum where we met Roland Gaul and the idea for this project began to take shape in my head. Roland Gaul then gave us directions to Mertzig and asked to stay in touch. We returned home at the end of the day, exhausted – but with a memory card full of images. Almost immediately, Opa started recognizing places and memories returned to him. “I remember it as if it were yesterday,” he’d say, almost incredulous. I could almost sense a curiosity in him, a desire to reconnect – but accompanied by fear.

After returning home to Chicago, I continued to research Opa’s story, resulting in the following document. Although initially just a hobby research project, it grew into something larger than I could have ever imagined or intended, involving many kind people and culminating with Opa’s visit to Mertzig on December 22nd of 2008 – the first time he’d faced his war in over 64 years. He was reluctant to go, seemingly plagued by demons from the past. He returned, hours later, much more at peace than I’d ever seen. This is his story.

Thorsten Herbes, January 2009

The phone call I’d been dreading came in May of 2011. It was late in the day here and calls from Germany at that hour were unusual. It was my father, telling me that my grandfather had beendiagnosed with terminal cancer. Less than three months later, we buried him.

Looking back at his life, he would appear to be a simple man at first. He lived in a small town in the Saarland region of Germany, worked as a Handwerker in construction and painting houses, fathered four children, loved to hunt and fish and passed peacefully, after a long life. Underneath, however, was a man deeply influenced by his experiences as an infantry soldier in World War II.

Born in 1923, he was still in his teens when he was drafted into the Wehrmacht. By the time he was 20, he had survived Stalingrad, the Wehrmacht’s biggest defeat thus far. After recovering from his wounds,he was sent back to the Eastern front, this time to Cherkassy, where he was soon wounded again. The final chapter of “his” war played out in the west, in December of 1944.

I had always been interested in his experiences in the war and only as I got older did I begin tounderstand truly how deeply it had affected his psyche and how profoundly long lasting its effects were on him. After researching the following story and having him talk about his experiences again, he developed nightmares again, so realistic that it felt to him as if the events had happened yesterday.

I put Opa’s story on paper mainly for my family, so that we wouldn’t lose the connection with history after he passed away. I wish I had started sooner and perhaps got him to tell me more about his experience in Russia, but I was too late. It is with some trepidation that I decided to share it with others through Rob’s blog (1infanteriedivision.wordpress.com), but I can’t think of a better way to honor a great man.

There is not a day that goes by where I don’t think about how much I miss him.

Thorsten Herbes

Hoffman Estates, IL

11/1/2012

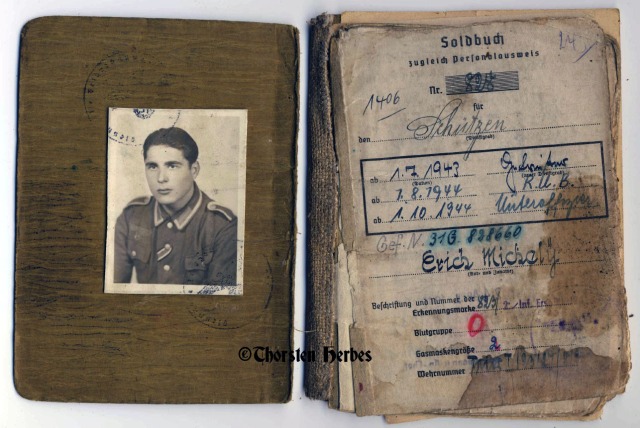

Michely’s Personal Documents – (No copying or distributing please)

Certificate of discharge from POW status

Ardennes Offensive, December 1944, 352nd Volksgrenadier Division

Situation, Western Front, December 1944:

By December of 1944, after five long years of war, the Allied Forces had landed in Normandy, successfully broken out, advanced across France and approached the Western borders of Germany.

Hitler’s Reich was being squeezed on two fronts and the Allies were preparing for their final assault into Germany. In a desperate attempt to drive the Allies back, Hitler devised a last-ditch effort to drive back the Allies, code-named Operation Herbstnebel (Autumn Mist). Under strict secrecy and radio silence, the Germans assembled two Panzer and two Infantry Armies as part of Army Group B in order to drive a wedge between the British-Canadian forces in the North and US forces in the South while capturing the important supply port of Antwerp, Belgium, after crossing the Meuse River. [2] Recapturing the port (which had only been opened by the Allies on 28 November) would deal a decisive blow to the Allied supply lines and ability to wage offensive operations against Germany.

Much of the history of what was to become “The Battle of the Bulge” concerns itself with the Northern flank of the German attack and Joachim Peiper’s attack on Bastogne, courageously defended by the 101st Airborne. The aim of this document is to explore the Southern flank of the German attack in the context of the personal experiences of Erich Michely, a member of the 8th Company, 2nd Battalion, 915th Regiment, 352nd Volksgrenadier Division – grandfather of the author.

The Southern Flank

Nestled between Belgium to the North and West, France to the South and Germany to the East, lays the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg. Founded in 963, it occupies an area slightly smaller than Rhode Island[4] and had a population of approximately 293,000 in 1945.[5] Luxembourg’s terrain consists of heavily wooded rolling hills with farm land and villages. By December 1944, Luxembourg had been liberated by the Allies after suffering from German occupation since 1940. Although the war continued to the east, life in the country was slowly returning to normal. No one suspected that the Wehrmacht would last much longer and the end of the war seemed imminent. By winter of 1944, Luxembourg had become a rest area for weary frontline GI’s as well as a quiet area in which to acclimate newly arrived replacements to the front. The war had become mostly static, with the Siegfried Line on Germany’s western border as the front. To the north, Field Marshal Montgomery’s troops were preparing for their eventual drive into Germany’s industrial heartland while, to the south, General Patton’s Third Army was also attempting to cross the Rhine into Germany.

The Americans

Headquartered in Bastogne, the US VIII Corps was responsible for the section of the line extending from southern Belgium to the southern end of Luxembourg. This sector was generally seen as a quiet front, used to recuperate units exhausted from the Huertgen Forest campaign earlier[6]. When Wehrmacht troops crossed the Our on 16 December, VIII Corps consisted of the 9th Armored Division, 11th Armored Division, 17th Airborne Division, 28th Infantry Division and the 87th Infantry Division, along with several AAA and Engineer units. Opposing the German’s 352nd VGD was the 28th Infantry Division, stretched along a 27 mile line from St. Vith in the north to Vianden in the south, with the 112th Regiment on the left (northern) flank, the 110th in the center and the 109th Regiment on the southern flank.

Under the command of Field Marshall Model, German Army Group B was comprised of the 15th Army, 5th and 6th Panzer Armies as well as the 7th Army. Tasked with conducting the attack, Army Group B covered a front from northern Belgium to southern Luxembourg, with 7th Army, under the command of General Erich Brandenberger responsible for the southern thrust into Luxembourg and toward the river Meuse.[8] Its main objective was not only to reach the Meuse but also protect the operation’s southern flank while tying up Allied reserve forces in Luxembourg. Although 7th Army contained several units (4 total divisions – 3 Volksgrenadier and 1 Fallschirmjäger), the focus of this document will remain with the 352nd VGD, of which Michely’s 915th Regiment was a part.

History of the 352nd Volksgrenadier Division

The 352nd Volksgrenadier Division was formed on 21 September 1944 in Flensburg, Germany out of remnants of the 352nd Infantry Division, which was almost completely annihilated in July of 1944 during defensive operations in Normandy, France. Units of the 352nd Infantry Division were augmented by the 581st Volksgrenadier Division, which was being formed as part of the 32nd wave.[10] The division consisted of navy and air force troops, veterans of the 352nd as well as veteran NCO’s from the Eastern front (such as Michely). Most of the NCO cadre was made up from remnants of the 389th Division, which was destroyed on the Eastern Front at Cherkassy (where Michely was wounded). The 389th also participated in the battle for Stalingrad during the winter of 1942 -1943 (of which Michely was also a part). By the time it was declared fit for combat, the352nd Volksgrenadier Division consisted of approximately 13,000 men, reflecting 98% of specified strength.[11]

According to Generalmajor Erich Otto Schmidt, Commander of the 352nd VGD: “I took over the division in October 1944. We continued to train until 15 November when we were moved to Bitburg, in the Eifel region, where we continued to train and supplement our equipment. Near the end of November, the division took over a section of the Westwall between Vianden and Echternach. 48 hours prior to the attack on 16 December, the division was led to its jumping off points between Roth and Wallendorf.”[12] Generalmajor Schmidt continues: “The division was formed and equipped according to standard specifications for Volksgrenadier divisions, with Ersatz troops drawn from navy and air force ranks.”[13] Prior to the attack, Schmidt rated his troops:[14]

Enlisted Personnel: Age 23 -30, not enough training, no land or combat experience, not seen action. Full strength.

Non-commissioned Officers: Mostly navy troops, most lack front experience. 75% strength.

Officers: Varied front experience. Full strength.

Infantry: Good fighting spirit in Regiments 914 and 915. Lacks training and front experience.

Equipment: Mostly complete. Missing 35% of radios for fire direction, 30% of assault guns, 25% assault rifles.

In general terms, the 352nd VGD was well equipped for 1944 but lacked in experience. The 352nd was made up of three infantry regiments (914th, 915th and 916th), an artillery regiment, one cavalry battalion, one anti-tank battalion as well as anti-aircraft, engineer and signal battalions. At full strength, the division made up about 13,000 troops.[15] Unteroffizier Erich Michely, veteran of two tours of duty on the Eastern Front, was assigned to 8th (Heavy) Company, 2nd Battalion, 915th Volksgrenadier Regiment, as a light infantry gun crew leader.

The 915th Regimental History up to 16 December 1944

After being wounded near Cherkassy, Russia, in March of 1944, Michely was transferred to a hospital in Lebach, Germany, near his home. After months of recovery and a brief period of leave, Michely received orders to report to the 915th Volksgrenadier Regiment near the town of Flensburg in northern Germany. It was during exercises in Flensburg that Michely was trained on using the 75mm infantry gun he would later lead during the Ardennes Offensive. The 75 mm guns were of a brand new variety, likely the 7.5 cm leichtes Infanterie Geschütz 42. These guns were not mechanized, but drawn by horses and were meant to be used as both light artillery as well as anti-tank weapons.

Each gun had a team of 4 horses and a crew of 7. “The names of the men on my crew were Otto, Kirnbauer, Abendrot and Kraft. I don’t recall the rest of them.” As a gun crew leader, Unteroffizier Michely was responsible for directing the gun’s fire and the welfare of his men and horses. “After recovering from the gut shot wound at Cherkassy, I was able to convince the doctors that I was no longer suited for service as an infantry soldier, as I had been in Russia. Personally, I simply didn’t think I’d survive another turn as an infantry man.” He was given special training and binoculars to locate targets and estimate range. Leading an artillery gun was an entirely new trade for Michely, who had been a machine gunner in an infantry unit during his time in Russia. For the first time he was also issued with the Wehrmacht’s new assault rifle, the MP44.

“Our regiment was spread out over several villages near Flensburg and we had little interaction with the other companies. I only knew the men in my crew as well as the other gun crew leaders, with whom I shared briefings.[18] When we finished training in November, we assembled on some sort of parade ground and were loaded on trains and began to head east. I wasn’t excited about the prospect of heading back to Russia and didn’t think I would make it home alive from a third tour”, recalled Michely. “We had made it to Poland but, sometime during the night, we must have changed direction. I was sleeping and didn’t notice the change until one of the men screamed ‘Mannheim, we’re in Mannheim!’ I asked him if he’d lost his marbles before we’d even reached the front, but he insisted that we were indeed in western Germany since he was from the area. Much to my surprise, he turned out to be correct.” The train continued to the southwest, at one point even coming close to Michely’s home town. “I asked the chief if I could go and visit my family for a few hours. He laughed and said ‘Michel[19], if I let you go, you’ll never come back.’” [20] The train continued its journey to the West, along a route taking the men through the ancient city of Trier to Bitburg until finally disembarking at Densborn, a mere 35 kilometers from the Our river.

By 26 November, the 352nd VGD had arrived in its assigned sector and began to occupy a portion of the Westwall near the Bauler – Echternach security zone, with division headquarters in Bettingen.[21] Michely’s company, after de-training at Densborn, continued on foot toward its assigned sector, near the town of Seimerich, resting in the small village of Feilsdorf for several days. The time in the ready area was spent with continued training as well as preparing positions for what appeared to be a defensive winter position along the Our. Michely’s men were unaware of any looming offensive. “We began working on a fortified position for ourselves along with the help of some Russian prisoners of war, who were marched in to assist us daily. Special care was taken to ‘winter-proof’ our dugout as much as possible, since we figured we’d be spending our time here defending the Our over the next few months.” Michely also recalls assisting a local farmer with his late-fall apple harvest. “We used our wagons to help him load and move the apples, most of which were on the ground by now. In return for our assistance, we worked out a deal with the farmer where he was going to give us a share of the apple Schnapps he was going to distill, so we could fortify ourselves for the winter too.”[22]

Although the average soldier in Michely’s unit appeared to have little clue as to their mission, signs were beginning to point to something big. “There were several occurrences, prior to the Division being informed of the planned offensive, which pointed to an impending large-scale combat action – but it was unclear who would be conducting the attack”, recalls Schmidt. “It was seemingly a miracle to all those involved that the Americans did not discover the offensive.[23]” Schmidt himself was informed of the attack in early December. The division was now tasked with several preparatory actions for the offensive, including the transport and delivery of all ammunition and bridge building materials inside the 5 kilometer restricted area within its assigned sector. This task was to be conducted at night and by means of horses.[24] Additionally, pathways were marked for troop movements, artillery positions prepared and supplies were deposited and camouflaged, intended for the first wave of attack. The troops themselves weren’t told of their mission until 6 hours before the attack was to begin.[25] The 915th regiment was to cross the river Our near Gentingen, the 916th near Ammeldingen and the 914th was to be in reserve.

The Battle Begins

16 December, 1944

At 0530 HRS, German artillery opened up along the entire 352nd sector, catching the Americans by complete surprise. Roland Gaul describes the initial barrage in his book: “The actual ‘firestorm’ was to begin at 5:30 AM from all weapons on the whole attack front (Monschau to Echternach) and consist of three waves of 10 minutes each; only after that should the specific firing missions be carried out.”[28] Generalmajor Schmidt reports: “352nd VGD was ordered to cross the river Our on 16 December at 0530 HRS between Roth and Wallendorf and move to take the (river Sauer, author) crossings at Ettelbruck and Diekirch as quickly as possible…The attacking troops were instructed to bypass enemy strong points and advance to the Sauer quickly.”[29]

On the opposite bank of the Our, American GI’s were dazed by the opening barrage but quickly began to organize a defense. Captain Embert Fossum, in charge of L Company, 109th Infantry Regiment, 28th US Division, was positioned directly across the river from the 916th VGR. Years later, Fossum recalled: “Company L, 109th Infantry, was the southernmost unit of the 28th Division when the German attack hit. Although the front was too wide to be adequately defended – approximately two miles – the ground it occupied was admirably adaptable for a defensive situation…During the [German’s] initial artillery preparation, which aroused the company at 0600 HRS on the 16th, the house where L company’s command post was located received a direct hit from both conventional artillery and Nebelwerfer rockets, which set it afire.” [30] At dawn, the first waves of German infantry began assaulting L Company’s foxholes on the western shore of the river, but were unsuccessful in dislodging the Americans.

Following its orders to bypass enemy strong points, advance units of the 915th crossed the Our by means of rafts, rubber boats, floats and footbridges.[31] The troops moved quickly and by nightfall had reached a wooded area near Bastendorf. Historian Bruce Quarrie describes the 915th’s move: “Screened by the mist which aided all of Seventh Armee’s assault companies, the leading two battalions fortuitously struck at the junction between the US 109th Regiment’s 2nd Battalion, whose Company E was in Fuhren, and the 3rd Battalion’s Company I deployed in front of Bettendorf. There was a 2,000-yard gap in between the American positions which the Volksgrenadiers exploited, advancing unopposed through Longsdorf and Tandel.”[32] The town of Bastendorf, as well as Longsdorf and Tandel remained in enemy hands.[33] When asked about his role during the first few hours of the offensive, Michely struggles to remember specifics, but it is unlikely that his company was part of the first wave across the Our. At Gentingen, the 352nd Engineer Battalion was working feverishly on completing a makeshift bridge across the river, capable of transporting the division’s heavy weapons, artillery and supplies.

17 December

By the next morning, the 915th still remained strung out, with its advance elements near Bastendorf and its heavy weapons, including Michely’s company, still awaiting the completion of the makeshift bridge across the Our. The regiment also suffered its first setback, losing its regimental commander, OberstLeutnant Johannes Drawe to a wound near Tandel. According to his personal diary, Drawe recalls: ”Sunday, 12/16/1944: 0430 HRS: went on duty. 0530: Began to fire. 0900; Personally crossed over and went on to Longsdorf. In Longsdorf 1300, command post set up. During the day directed following units; artillery commander and VB had no radio contact with firing batteries until 1800…Sunday, 12/17/1944: No supplies, no reports; 916 also in town. Constant medium-caliber harassing fire. Reconnaissance fails. 0730 commenced to move command post to Tandel. 0830: fighting in Tandel. Around 0900 wounded.”[34] The regiment now also faced stiffening resistance and was unable to clear Bastendorf, portions of Tandel and Longsdorf until later in the day, when it was taken by the division’s reserve regiment, the 914th.[35] By evening, engineers finally completed the bridge at Gentingen and heavy weapons and vehicles were allowed to cross. Although he does not recall, it is likely that Michely’s unit was among those to use the bridge at this time.

Meanwhile, units of the 109th Infantry continued to resist the attack, but were beginning to feel the effect of their losses. “…with an abundance of artillery support, L Company managed to beat back every attack [but] all of this was not done without considerable loss, both killed and wounded. And on the 17th all available manpower, including the company’s kitchen personnel, was brought up and put in the line.”[36] Reinforced in this manner, Company L continued to hold its position along the heights overlooking the Our, determined to slow the progress of the 916th and direct artillery fire on the river crossings.

Elsewhere, the remainder of the 109th Regiment was engaged in firefights all along its sector, stalling the attack but sustaining heavy losses.

18 December

As the advance troops of the 915th continued to wait near Bastendorf, Michely and his men made steady progress toward them. “We often moved cross-country, following the infantry and providing fire support where needed. I think we were also afraid to stay on the roads for too long, for fear of American [P-38] Lightnings.” Hindered by the rough terrain, the men were often forced to assist the horses in moving the guns. Many of the details of 8/915 route and events along the way have long left Michely’s memory, but several anecdotal stories remain. “The infantry at the front of the column needed artillery support and we had to get our guns up the hill to help them. The hill was so steep that we had to turn the guns around, with their barrels facing forward, hook all the horses to one gun at a time and push it up the slope ourselves. Eventually, we managed to get all four of them up the hill.” Michely continues: “I believe it was near Tandel where we came across two US tanks, unaware of our presence. We were looking down at them from an elevated position and our guns knocked both of them out. I don’t recall if any of the crew managed to get out.”[37] Given the horse-drawn means of transportation, Michely’s company always seemed to lag behind the advance infantry troops and thus avoided much of the combat they faced. “We maybe fired a dozen rounds or so throughout the entire Ardennes campaign.”

Entering the third day, the German attack was beginning to gain ground and force the American 109th to fall back. 1st and 3rd Battalion (Companies A and K) linked up and organized along the high ground south of Longsdorf, where K Company continued to face heavy attacks, resulting in the loss of an entire platoon to captivity. Company A, supported by one platoon of armor, attempted to fight its way into Fuhren to relieve Company E, 2nd Battalion, only to find the town empty and void of friendly troops and the command post burned to the ground.[38]

Company L was facing similar setbacks. “Shortly after noon on the third day, 18 December, the company was ordered, via [radio] to fall back to Bettendorf, the location of 3rd Battalion headquarters. This was accomplished with considerable difficulty and some casualties, as a limited penetration in I Company’s sector to the north enabled the enemy to cover the road back with automatic weapons fire.”[39] The company now took up defensive positions around Bettendorf, allowing the rest of the battalion to slip to the rear under cover of darkness to join the rest of the regiment in a newly selected defensive position on the high ground north and east of Diekirch.[40]

19 December

Throughout the night, L Company fell back to Diekirch as well, following the remainder of the battalion along the same route, one platoon at a time. The last group to leave Bettendorf assisted members of Company A, 103rd Engineer Combat Battalion to blow both bridges over the Sauer after crossing.[42]

Meanwhile, after three days of continued movement, German units finally managed to link up with the 915th near Bastendorf. “The division regained the ability to operate as a whole after linking with the 915th Regiment,” according to Generalmajor Schmidt.[43] It is likely that Michely’s unit had now joined the rest of his battalion in Bastendorf., where he had his first close call of the offensive. “I remember being in front of the church in Bastendorf. The church had a large wooden entrance door, flanked by two walls on either side. As a front-soldier, one develops a certain sense, perhaps instinct, and often acts without thinking. By this time, I was able to tell if incoming artillery fire was going to be close or land at a safe distance. I heard the round come in and instinctively jumped into the entrance of the church, even though the protection of the flanking walls was closer. The round detonated behind the wall, where it would have surely killed me, had I been there. To this day, I don’t know why I chose the door for cover instead.”[44]

Having finally regained its combat-effectiveness, the 915th quickly joined in the attack on the vital town of Diekirch, 2 miles south of Bastendorf. Company L, 109th Infantry Regiment, along with 1st and 2nd Battalion, had by now formed a defensive perimeter around the town, determined to stop the German advance. “The new position near Diekirch was held through the next day, 19 December, but was subjected to repeated attacks of both infantry and tanks. In a limited counter attack, directed toward the German road block which had cut the main road back [from Bettendorf], L Company’s first platoon captured 81 prisoners. In spite of these successes, by nightfall it was apparent that the regiment’s new mission of covering the flank of CCA, 9th Armored Division, could not be accomplished from this position, and another withdrawal to the south bank of the river [Sauer] at Ettelbruck was ordered.” This movement began after dark at a cost of 30 casualties from German artillery fire. When the company finally crossed the river, the bridge was blown and the night was spent digging in along the river bank through the town. [45]

When Michely’s company entered Diekirch, many of the men, poorly equipped for cold weather and hungry from lack of supplies, helped themselves to whatever they could find in the abandoned US positions. “The Americans threw more food away than we were issued,” recalls Michely. “We ate like kings from the rations we found in their supply depots and fighting positions.” Michely always appeared to be on the lookout for food, something perhaps learned from the misery of the Russian front. “I could smell freshly baked bread as we entered some of the houses and knew that it was unlikely that anyone would bake bread without also having some meat nearby. Being a farm boy myself, I decided to take a look around, along with my buddy, Obergefreiter Abendrot.” Contemporary Luxembourg homes often had a large chimney, which would form the centerpiece of the kitchen. Not only was it used for cooking and heating, but also for storage and slow smoking of cured meats, such as ham and sausages. “I decided to climb up into the chimney and found it to be ‘loaded’ with meat. The younger, or ‘green’ meat would typically be lower while the finished product would be higher up. As I climbed up higher, I must have knocked an entire green ham off its hook, because I heard a loud thump, followed by a scream. When I looked down, I saw Abendrot holding his head, where the ham had obviously made its impact. Nonetheless, despite the near loss of a comrade due to a falling piece of meat, we managed to ‘liberate’ an entire ham and some sausages, along with a crate of eggs.”

While Michely’s abilities as a scrounger kept his men well fed, they also exposed the polar opposites of an old-salt front soldier and a newly commissioned officer. Leutnant Clement was assigned to Michely’s infantry gun platoon as a forward observer and was fresh out of officer’s school. On several occasions, he and Michely had minor disagreements, typically resulting from Michely’s perceived lax sense of discipline. Despite being an instinctively proficient combat soldier, Michely never excelled at barracks-style discipline. After ‘liberating’ the ham and eggs, Michely’s gun and carriage looked more like a butcher shop than a combat weapon, with sausages hanging from the gun barrel. “Clement noticed our assortment of meats and chewed us out, asking how we expected to fight a war in such conditions. He ordered us to throw away the food and to make sure we were combat-ready.” Being the old-salt, Michely instructed one of his men to trail behind as he and the rest of the soldiers unloaded their bounty into the ditch. Thanks to his plan, the trailing soldier managed to gather much of the loot after the lieutenant had left. “Later that night, we fried up some eggs and ham to eat. The delicious smell must have attracted the lieutenant, because he came by and asked what we were doing – and then asked us if he could have some of our meal.”

The quest for a full stomach continues throughout Michely’s anecdotes. On another occasion, his men pulled into a small patch of woods to rest. Hungry and tired, Abendrot immediately began to fry up some of his eggs, while Michely and the rest of the men dug foxholes for themselves, in case of enemy artillery fire. “All of a sudden, incoming rounds started falling around us and I made a leap toward my foxhole – only to find it already occupied by Abendrot, who was also holding his pan of eggs. I had no choice but to climb in on top of him!” According to Michely, both men, and more importantly, their eggs, survived the barrage.

Unbeknownst to the Germans, 19 December also marked the day on which the expected US counterattack began to take shape. Commanded by General Patton, US Third Army, consisting of two Army Corps (III and XII) had managed to change its direction of movement from due east to due north and was beginning to reach its forward assembly areas near Luxembourg city, less than 20 miles away. The movement was the result of a meeting of General Eisenhower’s senior leadership in Verdun on the morning of the 18th.[46] On a collision course with the 352nd VGD was the US 80th Division, commanded by General McBride. At dawn on the 19th, the 80th Infantry Division had started for Luxembourg City. Company L, 319th Infantry Regiment mounted 2 ½ ton trucks near Hoelling, France at 1400 HRS and marched approximately three miles to a regimental convoy staging area, where serials are formed for the motor march to Luxembourg. Departure for the “Grand Duchy” commences at 2000 HRS with the entire regiment moving out en masse.[47] Similar movements are simultaneously occurring across the remainder of the division’s regiments. T/5 John Balas, member of L Company’s HQ recalls the ride: “We were told that there was some kind of breakthrough up north, issued a blanket a piece and loaded on trucks. This turned out to be ‘The Bulge’. We started from a rainy somewhat autumn [sic] day to a blinding snowstorm at the end of the trip. As we mounted up we were told not to get off the trucks, period; if we had to go to the bathroom, it was to be off the tailgate of the truck. No stopping for anything. That was the most miserable ride I ever had.”[48]

20 December

Unaware of the American reinforcements, the mission of the 352nd VGD was now to take possession of the river crossings at Ettelbruck, having already captured Diekirch. Upon taking possession of Diekirch, the left flank of the German attacking units discovered its bridge only to be damaged, not destroyed, allowing both infantry and heavy weapons to cross. It was decided to take advantage of this situation and use the 916th to cross the river Sauer in an effort to attack the strongly defended town of Ettelbruck from behind.[49]

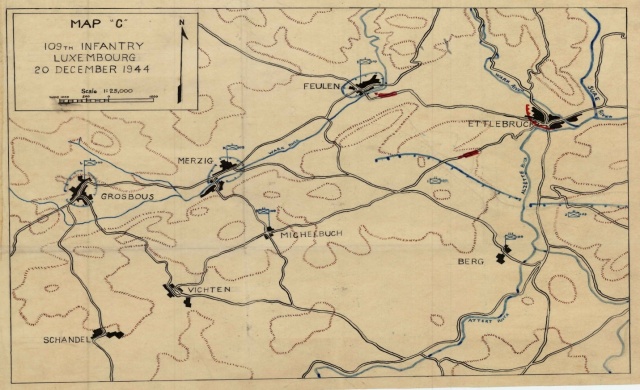

By now, realizing the dangerous nature of its unprotected left flank, the 28th US Division commander ordered the 109th Regiment to roll back with the 9th Armored. After pivoting to the south, the 109th had formed a line, generally facing north, at right angles to its original position, on the high ground south of Ettelbruck. [50] 3rd Battalion’s task was to cover the left flank of this line and was broken into three units, which were to be positioned at major road junctions to the west of this line. I Company was reinforced and moved to the village of Feulen. K Company, also reinforced, moved to Mertzig. Battalion headquarters was set up at Michelbuch. L Company was reinforced[51], renamed “Task Force L” and ordered to move 7 miles southwest and occupy the town of Grosbous.[52]

Bypassing Ettelbruck, advance units of the 915th began probing attacks on I Company’s positions near Feulen almost immediately, while the remainder of the regiment, along with Michely’s unit surrounded the town of Ettelbruck. Michely’s own position at this time is unclear but is likely on the high ground to the north of the town, as his platoon’s mission was to provide artillery support to the units attacking Ettelbruck.

21 December

Continuing its attacks on Ettelbruck, the 352nd VDG was finally able to capture the town, but found the bridge over the Sauer destroyed. According to Generalmajor Schmidt, the bridge was quickly repaired and the division’s infantry regiments are brought across and order to move out to their next objectives the following morning. The orders were as follows: 915th to move on Bettborn along the Feulen – Mertzig axis, 914th to move to Usseldingen along Michelbuch – Vichten axis and 916th to move due south. [54]

At around 1000 HRS, 1st Battalion, while fighting off several probing German attacks, managed to capture a German officer who carried an operational map outlining the mission of the 352nd and providing the Americans with valuable intelligence.[55]

Meanwhile, I Company continued to defend Feulen but was forced to withdraw, opening the road to Mertzig. The company retreated to the south-west, occupying the wooded heights running parallel to the road, tying in with 1st Battalion on the right and 3rd Battalion’s K Company on the left. Taking advantage of the open road, elements of the 915th, consisting of infantry and armor, pressed on against Mertzig and forced K Company to retreat to the south, astride the road to Michelbuch.[56] At 2100 HRS, a scouting patrol from the 915th advanced as far as the outskirts of Grosbous, 2 miles west of Mertzig, where it was met by Task Force L and repulsed, resulting in 31 dead.[57] By nightfall, the 915th was now firmly in control of Mertzig, but unable to take Grosbous. Its heavy weapons and trains remained behind, ready to join them the following morning.[58]

Continuing its move to the north, the US 80th Division now began to arrive in the area. Lieutenant Colonel Elliot Heston, commanding officer of the 3rd Battalion, 319th Infantry reported: “On the morning of the 21st, the battalion received orders to move to Brouch, about 16 kilometers northwest of the city of Luxembourg. The high ground in the vicinity of Brouch and Buschdorf was occupied, with the battalion defending to the north. During the night of the 21st orders were received to attack to the north at dawn the next morning until contact was made with the enemy, which was expected to be in the vicinity of Mertzig.”[59] The 319th would pass through the lines of Colonel Rudder’s 109th Regiment and relieve the tired troops. CT 319 moved by shuttle to its designated areas and cleared them at 1715 HRS, after which they posted local security and made preparations for the advance.[60]

The pieces were now in place for the American counterattack on the exposed left flank of the 915th Volksgrenadier Regiment.

Mertzig, 22 December 1944

The village of Mertzig stretches along its Rue Principale, in a slight south-westerly direction 2 miles west of Niederfeulen and 1.5 miles east of Grosbous, 15 miles north of Luxembourg City. The road runs along a valley, bordered by fields to the north and wooded hills and the River Wark to the south, set several hundred yards away. Several buildings, located in the very center of Mertzig in 1944, intersected by roads leading to the north (Rue de Merscheid) and south (Rue de Michelbuch) remain there today, with little change[63]. By the evening of 21 December 1944, 1st and 3rd battalion of 915 VGR had pushed through Feulen, taken Mertzig after a brief fight with K Company, 3/109 and established a HKL[64], facing south and west. Scouting elements advanced as far as Grosbous but came under fire from Task Force L around 2100 HRS. Halting for the night, 915 VGR was now preparing to continue its offensive operations, with 1st and 3rd battalions moving toward Grosbous and 2nd battalion preparing to head south, in the direction of Michelbuch. 8th Company, 2/915 was trailing behind, along with the regimental trains, in the general vicinity of Feulen.

After only a few hours of sleep, the company was told to water and feed the horses and move out, heading west in the dark. Moving quietly, soldiers walking and horses pulling the guns, the men advanced along the Feulen-Mertzig road, unaware of the Americans, who were dug in along the tree line to the south. By daybreak, and with Mertzig in sight, mortars and artillery began to fall, as I Company, 3/109 became aware of the Germans. “We came under fire as we entered Mertzig, but managed to reach the village without any casualties”.[65] Being an experienced front soldier, Michely knew that the threat of artillery would diminish as soon as his men would reach cover and were out of sight of the forward artillery observer who had spotted them.

To the men, Mertzig looked as though it had been deserted in a hurry, both by the civilian population as well as the Americans. Not having been resupplied in days and feeling relatively safe, the platoon left its guns and horses in the street (in front of Hotel Schammel) and began to explore the surrounding buildings. Entering the hotel on the south side of the street, the men found the dining room empty but the beer taps full, and immediately began serving themselves. It was now mid-morning and snow started to fall. Little did Michely know that 22 December 1944 was to be his last day in combat.

Earlier that morning, advance liaison officers of the US 80th Division made contact with their counterparts from the 28th and immediately coordinated moving the 317th, 318th and 319th Infantry Regiments through the lines and attack to the north, along the Luxembourg – Ettelbruck highway axis. Supported by units from the 702nd Tank Battalion and the 610th Tank Destroyer battalion, 3rd Battalion of the 319th Infantry Regiment was given the order to move north from Vichten into the direction of Michelbuch and attack Mertzig from the south. Moving cautiously, 3/319 had made steady progress and was now arriving at the heights, overlooking the village.

While his men were celebrating in the hotel bar, Michely explored the remainder of the building, liberating copious amounts of beer and wine. It is unclear why Michely did not take part in the feast but during many conversations with the author, he expressed having developed a sixth sense while on the Eastern Front[67] – a sense which had saved his life on several occasions. “On one end of the building was a bowling alley, with clear views to the south. To my horror, I saw American troops descending from the ridgeline only a few hundred yards away. Our guns were still harnessed to the horses and no defensive positions or security had been established. The men were completely unaware until artillery began to fall into the street moments later.” Michely had just seen the beginning of the attack by 3/319, with companies K and L abreast and M (Weapons) in reserve.

“As we rushed into the street, we discovered that several of our horses had already been killed or wounded by artillery and others, cut loose and frightened, were running off into the direction of the attack, trailing behind them the wagons containing our ammunition supplies. For a moment I thought about using my weapon to shoot the horses and keep them from ‘surrendering’, but I didn’t.” The men now attempted to make the guns ready to fire, despite the completely exposed positions in the road. “I was running from gun to gun when a tank appeared next to the dairy building, only a few hundred yards away. Gefreiter Erich Otto’s gun and crew were completely exposed in the intersection of Rue Principale and Rue de Merscheid but were determined to knock out the tank.” The next events happened in a matter of seconds. “I could see the turret of the tank turning into the direction of the exposed gun and screamed at Otto and his men to take cover as I dove into the front door of a house. I don’t know if it was the tank or a direct hit by artillery[68], but when I looked at the gun, I saw the flash of an explosion with pieces of the gun and its crew flying through the air.” The gun and its crew, Gefreiter Otto and Obergefreiter Kirnbauer, were gone in an instant.

The attack on Mertzig was conducted by the 3rd battalion of the US 319th Infantry Regiment and documented in its official regimental history.

“The mission of CT 319 was to continue the attack to the north. The 1st and 3rd battalions jumped off into the attack at 0600. At 0735 leading elements of the 3rd battalion had reached their first objective meeting little resistance. At 0800 the 1st battalion had also met no resistance. At the same hour (0800) the 3rd battalion had placed elements in Vichten where the 109th Infantry of the US 28th Division was stationed. At 0910 the 3rd battalion entered Michelbuch and gained contact with the enemy. At 1000 the 1st battalion reported no contact with the enemy. The 3rd battalion cleared Michelbuch and prepared to move on Mertzig with companies L and K (on the right) abreast at 1010. At 1040 one platoon of Company C, 702nd Tank Battalion entered Mertzig and at 1100 companies K and L reached the high ground in the vicinity meeting no resistance. At 1145 1st battalion advanced and met small enemy patrols. At 1205 the 3rd battalion was in Mertzig receiving considerable enemy small arms fire and light artillery.”[70]

Sgt. Hanright, a platoon sergeant in K Company, 319th, recalls the attack on the village. “We moved out from our positions overlooking Mertzig from the south at around 1100 HRS. Our company was on the right flank of the attack and quickly covered the open ground between the tree line and the houses on the edge of the main road. We reached a house (which I later found out to be the mayor’s house) with a fenced-in yard and three or four concrete steps leading up to the front door (Maison Rausch). Upon entering the house, we found a set of stairs to the basement and I was about to throw in a grenade when I heard a sound which made me stop. I eventually took 22 or 23 German prisoners who had been hiding in the basement[71].” Upon clearing the house, Sgt. Hanright’s platoon turned east and continued clearing houses along Rue Principale, using a captured German officer to encourage more troops to surrender.

Company L experienced similar events. T/5 Balas recalls: “About 0300 (22 December, author) we were abruptly awakened by the Sarge and had a hot breakfast. Then, we marched through the snow to the front lines. This was roughly a 20 mile hike with full equipment…After hours of walking, we came to the last elements of the rear guard (109th Infantry Regiment, author) on a ridge dug in among some trees…Down below in the valley we could see a cluster of buildings with a road leading away…After a friendly barrage of mortars and artillery, we attacked, surprising the Krauts…”[72]

Private Krehbiel, a newly arrived replacement from 2nd Platoon continues: “By early afternoon we arrived on some high ground overlooking a village in a valley, but as I remember, the slope into the town wasn’t really steep. As we jumped off, I recall our platoon leader, Lieutenant Nauss, double timed us over some open ground to the right of the Company into the cover of some trees[73]. However, the Krauts began firing on us and we sustained a casualty or two on the open ground before we managed to secure a foothold in the first buildings.”[74]

As the Americans continued to attack, the situation in the street became increasingly dangerous and untenable for Unteroffizier Michely and his men. Having lost their horses, at least one gun and most of their ammunition (except for the 4 or 5 ready-rounds kept with each gun), the men decided what to do next. “We abandoned all but one of the remaining guns and pushed it up a street to the right of a large farm house (the farmhouse was Maison Weis and the street was likely Rue de Merscheid, author). By the time we reached the top of the hill, a few hundred yards to the north, we realized that the gun had a flat tire and its sighting mechanism had been damaged.”[75] It is unclear whether the men managed to push the gun along the road or along a small path behind several farm houses directly to the east of the road. Given the buildings’ location, both routes offered much needed cover from the enemy fire, which by now also included direct fire from heavy .50 caliber machine guns. “We reached a small, free-standing house at the top of the hill (25 Rue de Merscheid[76]) and decided to return fire with our remaining gun, as we now had a direct line of sight over the top of the houses along the main road and into the tree line from which the Americans were advancing. Since the gun sight was destroyed, we bore-sighted the gun and took aim at some of the truck-mounted heavy machine guns. In order to better direct our fire, I positioned myself under the barrel of the gun, lying prone and using my binoculars to spot the enemy. Our first shot unleashed a hornet’s nest. Never in my life had I experienced such intense machine gun fire, not even in Stalingrad!” Michely continues: “Rounds were impacting all around me, but, luckily, they must have been poor shots, since most of them appeared to be aimed high. Nonetheless, I was trapped under the gun, unable to move and marveling at the sheer amount of fire power and ammunition they must have had available to them – they had more ammunition per machine gun than we had for our entire regiment!” Using his experience, Michely waited until the enemy machine gun crew had to change ammunition belts or barrels. “As soon as there was a lull in the fire, we took the opportunity to fall back. There was a door to the basement of the house, with two metal flaps parallel to the ground. We opened the door and found ourselves in a small, perhaps 10’ by 10’ basement room with a vaulted ceiling. There were 7 or 8 of us in the room.”[77] The men in the basement were members of the platoon, but not of Michely’s gun crew. “I can’t say for certain how long we were in the basement, but we could hear the machine gun rounds hitting the walls of the house. We decided to make our way toward the center of the village.”

Shortly after leaving the basement, the group encountered Leutnant Clement, the platoon’s VB or forward observer, along with his runner. Clement was young and had only recently graduated from officer school. “He was 19 or 20 years old and had little or no experience in combat, other than what he had learned in school. After fighting in Russia, house-to-house combat was something I was quite familiar with.”[78] Michely continues: “I realized the situation was hopeless and told Leutnant Clement that my war was over and that I intended to surrender to the Americans at the earliest and safest opportunity. I suggested that he and the rest of the men should do the same.” Leutnant Clement disagreed and ordered that the men attempt a breakout to the northeast in order to join the rest of the battalion. Michely did not think that a breakout attempt was feasible. “Where are we going to go? They’ll shoot us like rabbits!” Upon hearing Michely’s refusal, Clement warned him that he would report him to the company commander and court-martial him for desertion.[79] “Before you can do that, you have to survive first,” countered Michely. “Against our advice, Leutnant Clement and his runner then decided to head out, attempting to cross the open meadow east of Rue de Merscheid. After only about 35 yards, I witnessed Clement get hit and tumble over, dead. His runner was shot through the collar of his greatcoat while another bullet merely grazed him in the neck – but was otherwise unharmed.”[80] Leutnant Clement’s death now made Unteroffizier Michely the highest-ranking remaining soldier in the platoon.

The decision was now made to move toward the Americans in an effort to surrender[81]. Michely advised his troops not to shoot, under any circumstances. Making their way down along Rue de Merscheid, the men found a gate in the wall separating them from the park-like area behind Maison Weis and were soon within the cover of the row of buildings along the Rue Principale, in complete defilade from the fire coming from the tree line along the ridge across the Wark. In 1944, the terrain was open, with several trees, small ponds and a small brook, the Turelbach. Facing south, the men were behind three buildings, with the Maison Weis on the left, the saw mill on the right and the machine house in the center. The machine house was adjacent to the brook and contained the components needed to drive the saw mill.[82] The men entered the machine house and made their way into the basement. “There were long concrete corridors and all kinds of machinery, which must have been connected to the saw mill”, Michely recalls. “We could see logs outside, by looking through windows on the south side of the basement. Crawling over the logs were ‘Amis’, advancing toward us. I could clearly see their legs and short rifles (carbines, author).”

What happened next is unclear and has likely suffered in detail by the passage of 64 years. During one conversation with the author, Michely recalls: “There were perhaps 8 or 10[84] of us in the basement. I knew the men were from my platoon, but none of them were part of my gun’s crew. We could see the Americans advancing cautiously over the logs. I don’t think they saw us yet. I told them (my men, author) not to shoot under any circumstances. Someone fired a shot at the Americans, dropping one GI. I couldn’t tell who had fired due to the dim light in the room and no one took responsibility for the shot during my ensuing tirade.” The remaining Americans took cover and possibly returned fire. Somehow, according to Michely, “we heard them call for a flame thrower and decided that we needed to surrender immediately.”[85] Michely told the men that now was the time to surrender and that he wasn’t going to force anyone to hold out. Each man was free to decide. Two of the men climbed up the stairs with their hands in the air – only to be fired upon immediately. Unharmed, the men jumped back into the basement and screamed “Michel, they don’t want to take us prisoner!” Michely angrily screamed back at the men. “What do you expect after the a*****e shot at them?” Michely now realized that the responsibility for the men was his, since he was the highest-ranking soldier. Frightened, he saw no other option but to lead the men up the stairs. “We would have died in that basement for sure. I took my MP43 and my binoculars and threw them over a wall behind which I heard the sounds of running water[86]. I assumed it was the small stream we saw on our way and wanted to make sure that the Americans wouldn’t get my weapon and glasses. Raising my hands over my head, I climbed up a steep set of steps leading to the outside.[87] At the top of the steps was a US soldier, pointing his rifle at me. I remember tripping while climbing up the stairs with my hands over my head and falling forward. Instinctively, I reached out and grabbed the ankles of the soldier to stop my fall. They must have thought I was trying to pull him into the basement, for I immediately received a blow to the back of my head by an unseen soldier’s rifle butt. He hit me so hard that I saw stars.”

Despite the fall, Michely and his men managed to climb out of the basement and surrendered. “I remember seeing tanks and a lot of troops. We were searched and lined up against a wall. I had told the men to remove any articles of US clothing they might have on them, as many of them had taken advantage of the warm winter clothing we found in abandoned US supply depots. One of the men must not have heeded the warning as, all of a sudden, a shot rang out and he was killed.” It is unclear whether this was due to him wearing a GI’s coat or an act of revenge. “I thought they were going to kill us all”, Michely remembers, “but then an officer appeared, gesturing wildly. I couldn’t understand what he was saying, but no more prisoners were killed after that.”

After the lineup, the remaining men were assembled and transported to Mersch. Michely was elated at being alive and remembers meeting another “old salt” non-commissioned officer from his unit along the way. “We had both been through combat in Russia and were happy to have survived this one”. After being processed in Mersch, the POW’s were loaded into railway cars and transported into captivity. After several months in camps near Normandy, France, Erich Michely would return home to his family on November 13th, 1945 – his 22nd birthday.

By nightfall on 22 December, the Germans held the north end of the town, with the Americans firmly dug in on the south.

While all of this took place, two additional elements of the 915th met unexpected attacks as well. By 1000 HRS, as the snowfall began to lessen, outposts from Task Force L, who by now had moved to positions on the high ground overlooking the road from Mertzig to Grosbous, observed a large column of enemy infantry and vehicles on the move toward Grosbous.[91] The column stretched for almost a mile and a half and consisted of several artillery pieces, vehicles, infantry and two light tanks, apparently completely unaware of Task Force L’s presence a mere 1,300 yards away.[92] The entire column was destroyed with direct and indirect fire from Task Force L and the 108th Field Artillery Battalion. The result of the 20 minute ambush was the complete destruction of the 915th’s spearhead, at the cost of one wounded soldier for Task Force L.[93]

Just as the advance units were being destroyed, the tail end of the 915th also met its end – at the hands of 1st Battalion, 319th Infantry Regiment. The heavy weapons and supply trains were moving along the road from Feulen to Mertzig in almost parade-ground-like formation when 1/319 began its attack north across the road. The result was complete destruction. Corporal Clement Good remembers driving along the road later that night: “As driver for the division artillery’s HQ battery commander, I often had to drive along the roads at night to deliver messages or look for breaks in our telephone lines. After the combat at Mertzig, I was driving down the road without any headlights for fear of being detected. The Dodge Command Car kept going over what appeared to be large bumps in the road. It wasn’t until daylight that I realized I had been driving over the carcasses of German horses.”[94]

By the end of the day of 23 December, Mertzig had been completely cleared of any German resistance and the German advance had ground to a halt just west of Grosbous. Cut off from reinforcements, the remaining troops of the 915th were ordered to abandon their heavy equipment and break out, making their way back to Ettelbruck. Over the course of the next month, the Regiment continued to take part in defensive operations in the Ettelbruck bridgehead, eventually falling back to its original positions across the Our on 21 January, 1945. Hitler’s final offensive in the west had been stopped, at a cost of 8,000 men to the 352nd VGD alone.[95]

The War Ends

By March of 1945, Germany was defeated and only weeks away from unconditionally surrendering to the Allies. Ironically, the same unit who took Michely prisoner, would eventually capture and briefly occupy his home town as well, entering Michelbach, Germany on 17 March 1945.[96]

Erich Michely still resides in Michelbach today, along with his wife of 61 years, Loni. Upon his return from captivity, he started a family which eventually grew to 4 children, 5 grandchildren (with a 6th on the way) and one great-grandchild. He spent his life as a construction worker and forester and enjoys his garden and apple orchard. On 22 December 2008, 64 years to the date, he revisited Mertzig, Luxembourg, where he was received with open arms and retraced his steps of his last day as a soldier.

Acknowledgements

This document is the result of months of research and could not have been made possible without the generous help of the following people, many of whom were sucked into the vortex along with the author:

Marcel and Manfred Michely, sons of Erich Michely, both of whom spent countless hours researching and countless dollars on long-distance phone conversations with the author. Fernand Pletschette, Erny Kohn and the remaining members of the Mertzig Historical Society. Fernand answered the author’s e-mail out of the blue and was instrumental in pulling in local information, finding images, composing presentations and coordinating Michely’s visit to Mertzig in 2008. Claude Staudt, honorable mayor of Mertzig, who welcomed Michely with open arms and open doors. Roland Gaul, curator of the Luxembourg National Military Museum, for his knowledge and willingness to help. Mr. Gaul’s books are a one-of-a-kind resource and his work is extraordinary. Robert Hanright, Robert Murrell, Bill Krehbiel and Clement Good for assisting the author in obtaining American eye witness accounts.

Kyla Herbes for being a trooper and encouraging the author’s obsession.

Finally, and most importantly, Erich Michely, the inspiration for this project and to whom it is dedicated.. It is through your experiences that we can hope to remember the past and learn from it. Opa, thank you for always indulging me with your stories. Thank you for your example and courage.

German Order of Battle (352 VGD)

- Division Command (HQ)

- Command Staff & Field Police

- Feldpost Number 29750

- Grenadier Regiment 914

i. Regiment Commander: Oberstleutnant Johannes Drawe, wounded at Tandel 12/17/1944

ii. Regimental Adjutant: Oberleutnant der Reserve Wilhelm Ifang

iii. 1st Ordnance Officer: Leutnant Rudolf Kalberlah

iv. 2nd Ordnance Officer: (rank unknown) Georg Kunze, wounded at Longsdorf, 12/18/1944

v. Officer z.b.V.: Oberleutnant Sepp Herrmann

- Staff Company

i. CO: Leutnant Eduard Seidl, wounded at Kippenhof (Diekirch) 12/24/1944

ii. Communications Platoon: Leutnant Karl Dirks, wounded at Oberfeulen 12/22/1944

iii. Pionier Platoon: Leutnant Reinhard Bennemann, wounded at Tandel 12/17/1944

- 13th Company (Infantry Gun)

i. CO: Leutnant Friese, missing at Mertzig, 12/22/1944

ii. Platoon Leader: Leutnant Heinrich Brande, missing at Mertzig, 12/22/1944

iii. Platoon Leader: Leutnant Otto Luhr, missing at Mertzig, 12/22/1944

- 14th Company (Panzerjager)

i. CO: Leutnant Otto Griese, wounded at Longsdorf, 12/16/1944

ii. Platoon Leader: Leutnant Franz Michaelis, missing at Mertzig, 12/22/1944

- Staff, 1st Battalion

i. Battalion CO: Hauptmann Heinrich Konig

ii. Adjutant: Gerhard Ihl, wounded 12/21/1944, location unknown

iii. Ordnance Officer: Karl Heinz Jantschak

- 1st Company

i. CO: Leutnant Alwin Feldhans, KIA 12/21/1944 at Ettelbruck

ii. Platoon Leader: Leutnant Horst Dietrich, missing 12/22/1944

- 2nd Company

i. CO: Leutnant Rudolf Rothfelder, KIA at “Friedhaff” Diekirch, 12/17/1944

ii. Platoon Leader: Leutnant Wolfgang Kluth

- 3rd Company

i. CO: Oberleutnant Albrecht Schubert

ii. Platoon Leader: Leutnant Reinhold Tietje

- 4th Company

i. CO: Oberleutnant Otto Muhlert, wounded at Pratz, 12/22/1944

ii. Platoon Leader: Leutnant Ludwig Vorst

iii. Platoon leader: Leutnant Georg Witt, missing at Mertzig, 12/22/1944

- Staff, 2nd Battalion:

i. Battalion CO: Hauptmann Herbert Kruger

ii. Adjutant: Wilhelm Leimbach, wounded at Tandel 12/16/1944

iii. 1st Ordnance Officer: Leutnant Paul Flocke

- 5th Company

i. CO: Oberleutnant Arthur Schulz, took sick 12/31/1944

ii. Platoon Leader: Leutnant Bruno Brassel, wounded at Mertzig, 12/22/1944

- 6th Company

i. CO: Leutnant Heinz Jagers, wounded 12/31/1944, location unknown

ii. Platoon Leader: Leutnant Heinz Ruckert, KIA at Longsdorf, 12/17/1944

- 7th Company

i. CO: Hauptmann Walter Langendorf, missing, date/location unknown

ii. Platoon Leader: Max Stalke

- 8th Company (Schwere)

i. CO: Oberleutnant Gunter Rolf

ii. Platoon Leader: Leutnant Werner Perlsberg

iii. Platoon Leader: Joseph Clement, missing at Mertzig, 12/22/1944

Platoon List:

Michely’s hand-written list of company members. A “V” after the name denotes vermisst (missing), a cross indicates killed.

Bibliography

Collins; Keegan John, ed. Atlas of the Second World War. Ann Arbor, MI: HarperCollins in association with Borders, 2003.

Fossum, Embert. The Operations of “Task Force L”, 109th Infantry (28th Division) near Grosbous, Luxembourg 20 -23 December 1944. Fort Benning, GA: US Army Infantry School, Advanced Infantry Officers Course, 1948.

Gaul, Roland. The Battle of the Bulge in Luxembourg: The Southern Flank, December 1944 – January 1945. Volume I: The Germans. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Military, 1995.

Gaul, Roland. The Battle of the Bulge in Luxembourg: The Southern Flank, December 1944 – January 1945. Volume II: The Americans. Atglen, PA: Schiffer Military, 1995.

Janes, Terry D. Patton’s Troubleshooters, Revised Edition. Kansas City, MO: Opinicus Publishing, 2006.

Krehbiel, Bill J. The Pride of Willing and Able. Published by Krehbiel, 1992.

Murrell, Ed. 319th Infantry History, ETO 80th “Blue Ridge” Infantry Division. Oakmont, PA: Published by Author, year unknown.

Quarrie, Bruce. Order of Battle 12: The Ardennes Offensive, I Armee & VII Armee. Oxford, UK: Osprey, 2001.

Quarrie, Bruce. Order of Battle 13: The Ardennes Offensive, US III & XII Corps. Oxford, UK: Osprey, 2001.

Schmidt, Otto E. After Action Report, 352nd Volksgrenadier Division. Location, publisher and date unknown.

Schmidt, Otto E. “Project 22” Ardennen Offensive. Location and publisher unknown, 1950.

US War Department. Handbook on German Military Forces. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press, 1990.

Various oral interviews with Michely, Hanright and Good. Conducted by author, 2008 – 2009

Authors: Robin Schäfer & Herr Thorsten Herbes.

[1] http://memory.loc.gov/ammem/collections/maps/wwii/essay1a.html

[2] Collins, Atlas of the Second World War, Page 160

[3] Arnold, p 27

[4] CIA Fact Book

[5] www.luxembourg.co/uk

[6] Fossum, page 5

[7] Quarrie, Volume 13, Page 11

[8] Collins, page 161

[9] Quarrie, Volume 12, Page 9

[10] http://spearhead1944.com/gerpg/ger352.htm

[11] Gaul, Volume I, Page 22

[12] Schmidt, page 2

[13] Infantry Regiments 914 and 915 were formed from navy troops, while 916 was drawn from air force personnel. See Appendix for detailed listing.

[14] Schmidt, page 4

[15] See Appendix II for detail

[16] Lexikon Der Wehrmacht

[17] http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/File:Sturmgewehr_44.jpg

[18] Author’s note: There were 4 le. I.G. 42 75 mm infantry guns in the company. Each gun was led by a non-commissioned officer (Unteroffiziere Grau, Lemke, Mizera and Michely).

[19] Erich Michely’s nickname

[20] Although Michely had thought about deserting, he knew that his family would be punished for his actions – a common practice near war’s end. He did, however, promise his father to attempt to go into captivity as soon as it was safely possible.

[21] Gaul, Volume I, page 52

[22] Michely’s fondness for apples and Schnapps continues to this day

[23] Schmidt, Project 22, page 6

[24] Schmidt, Project 22, page 7

[25] Schmidt, Project 22, page 7

[26] Gaul, Volume I, page 53

[27] Quarrie, Volume 12, page 19

[28] Gaul, Volume I, page 50

[29] Schmidt, Project 22, page 8

[30] Fossum, page 10

[31] Gaul, Volume !, 55

[32] Quarrie, page 34

[33] Schmidt, Project 22, page 9

[34] Gaul, Volume I, page 77

[35] Schmidt, Project 22, page 10

[36] Fossum, page 11

[37] The author has been unable to confirm the loss of two tanks near Tandel throughout his research, but believes the story to be true.

[38] 109th Infantry Regiment December 1944 AAR, page 5

[39] Fossum, page 11

[40] Fossum, page 11

[41] Map courtesy of Captain Embert Fossum, www.infantry.army.mil/monographs/content/maps/StudentMaps/FossumEmbert%20A/Map%20BB.jpg

[42] Fossum, page 12

[43] Schmidt, Project 22, page 11

[44] It was this story which sparked the entire research project for the author. After hearing it for the first time in September 2008, the author decided to drive to Bastendorf to take pictures of the church and find out if any shell damage remained. As it turned out, a new church was built in 1948, replacing the old one.

[45] Fossum, page 13

[46] Quarrie, Volume 13, page 16

[47] Krehbiel, page 111

[48] Krehbiel, page 111

[49] Schmidt, page 11

[50] Fossum, page 8

[51] See Appendix III

[52] Fossum, page 13

[53] Fossum

[54] Schmidt, Project 22, page 11

[55] 109th Infantry Regiment, AAR, page 7

[56] Fossum, page 26

[57] Fossum, page 26

[58] See Appendix IV

[59] 319th AAR, pp. 1-2

[60] Murrell, page 43

[61] Fossum

[62] Image courtesy of Fernand Pletschette. Rue de Michelbuch runs along the bottom of the image, while Rue Principale stretches from bottom-right to top-left. The first three building along the right side of Rue Prinicpale are Maison Weis, the machine house and the saw mill. Hotel Schammel is on the left side of Rue Principale, first house on bottom-right corner.

[63] See Appendix V for map

[64] Hauptkampflinie, Main Line of Resistance

[65] Michely

[66] Image courtesy of Fernand Pletschette. Image shows Hotel Schammel in 2008. Point of view is looking east, along the main road. Michely’s guns were parked facing the viewer, along the front of the building, just prior to the attack.

[67] Author’s note: Michely was also quite displeased at having his meal ‘interrupted’ by the attack.

[68] Author’s note: Michely later recalled a second tank, moving west-to-east along Rue Principale. It is plausible that Gefr.Otto’s gun and crew were killed by a round from this second tank.

[69] Image courtesy of Fernand Pletschette. Image shows Rue Principale in 1944, looking east. Maison Weis is on the left, the dairy building on the right. Obergefreiter Otto and Gefreiter Kirnbauer died in the intersection immediately past the second building on the right.

[70] Murrell, page 45

[71] Hanright

[72] Krehbiel, page 113

[73] Author’s note: Based on research, the open ground may have been the meadow immediately west and south of the dairy building, with trees running parallel to Rue de Michelbuch.

[74] Krehbiel, page 114

[75] Michely

[76] See Appendix

[77] On 22 December 2008, Michely returned to Mertzig and was able to locate the basement room which had once saved his life. The ceiling had changed, but the metal flap doors covering the entrance were still there and he recognized it immediately.

[78] Michely

[79] Author’s note: An avid opponent to war then and now, Michely always maintained the righteousness of his decision to surrender and does not see his decision as desertion. To him, the insanity of continuing an already lost war was not worth his own death. The decision to surrender was made by each individual member of the platoon and of their own free will.

[80] Leutnant Clement is still officially listed as “missing”. Michely also told the author about being upset that he had been forced to give Clement his “good” compass earlier, which was now also lost.

[81] Author’s note: There appeared to be a lull in the fighting, or at least the amount of incoming fire had decreased substantially.

[82] Author’s note: Neither the machine house nor the saw mill exist today. The machine house was torn down in the 1970’s and in its place (and the former saw mill) is now the Centre Turelbach, a community center. Maison Weis still remains and is Mertzig’s village hall today.

[83] Image courtesy of Fernand Pletschette. The house in the center is the machine house. The background also clearly shows the high ground and tree line from which the 319th attacked.

[84] Michely’s recollection. He does not know whether Leutnant Clement’s runner was with them or not.

[85] Author’s note: One of Michely’s men was Polish and claimed to have heard the American troops request a flame thrower. Whether he spoke English or whether there were Polish-speaking GI’s remains unclear.

[86] The machine house contained a paddle wheel, driven by the Turelbach, which was re-routed through the basement for this purpose.

[87] Authors’ note: According to research, these steps were on the northwest corner of the building.

[88] Image courtesy Fernand Pletschette

[89] Image courtesy of Fernand Pletschette. German POW’s (likely from the 915th regiment) await transport into captivity in Mertzig.

[90] Image courtesy of Fernand Pletschette

[91] Fossum, page 31

[92] Fossum, page 32

[93] Fossum, page 33

[94] Interview with the author

[95] Fossum, page 36. By 24 December, 352nd’s strength was estimated at 5,000 men.

[96] Krehbiel, page 189

[97] Krehbiel, page 315

[98] Image courtesy Fernand Pletschette. Left to right: Claude Staudt (mayor of Mertzig), Fernand Pletschette, Marcel Michely, Erich Michely, Manfred Michely, Jos Clees, Roland Gaul. Picture taken 22 December 2008, on the steps of Maison Weis.

[99] Quarrie

[100] Handbook on German Military Forces, page 97

[101] Handbook on German Military Forces, page 116

[102] Handbook on German Military Forces, 119

[103] Gaul, Volume I, Pages 22-23

[104] Gaul, Volume I, Pages 28-30

[105] Courtesy of Erich Michely. PLEASE DO NOT COPY OR PUBLISH!

[106] Gaul, Volume II, Page 13

[107] Embert Fossum, “Operations of Task Force L near Grosbous, Luxembourg, December 20 – 23, 1944”, Page 4

[108] Murrell

[109] Quarrie

–>