What could have happened to the 9th Legion? How could it simply disappear? The fate of the 9th has been the subject of debate for scholars for almost three hundred years.

In the period between 108 AD and around 160 AD, one of the most experienced legions vanished from the strength of the Imperial Roman Army. It was last recorded as serving in Britain but there is no record of what subsequently happened to the Legio IX Hispana and its fate has given rise to intense debate and speculation.

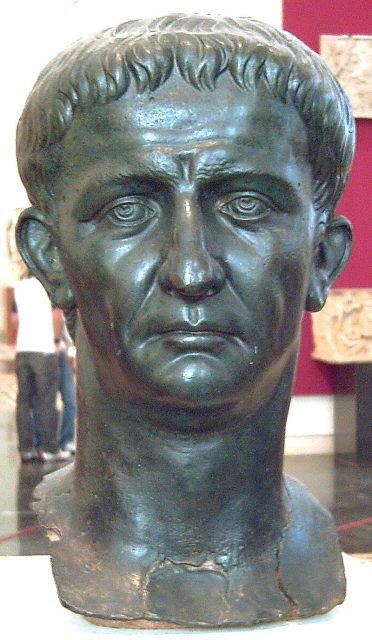

When the new Emperor Claudius took control of Rome in 41 AD, the IX (9th) Legion (also identified as Legio VIIII) was one of the oldest in the imperial army. The 9th had first been raised in Spain (Hispana) in around 50 BCE by Pompey before being inherited by his arch enemy Julius Caesar who used it in his campaigns in Gaul.

After the death of Caesar, the 9th fought on the side of Caesar’s great-nephew Octavian in his war against Mark Anthony. When Octavian triumphed and became the Emperor Augustus in 27 BCE, the 9th was established as one of the most trusted core units of the new imperial army.

Almost seventy years later, Claudius became Emperor and decided on an invasion of Britain. Rome had established trading links with Britain during Julius Caesar’s expeditions there in 55 and 54 BCE.

However, Claudius wanted a full-scale occupation of the country and sent Aulus Plautius, a respected Roman military leader and politician, to lead four of the most experienced legions across the English Channel in 43 AD.

The main force comprised around 20,000 men from four legions; the 2nd, 9th, 14th and 20th plus around the same number of auxiliaries. Each legion was given a different objective and the 9th was sent north as far as present-day Lincoln in the East Midlands of England.

By around 47 AD, most of southern part of Britain was under Roman control. Then, in 60 AD, an uprising led by Boudicca, a queen of the Celtic Iceni tribe, plunged Roman Britain into chaos. The 9th was heavily involved in suppressing the revolt and suffered very heavy casualties in several battles – records show that it lost up to one-third of its total strength during these battles.

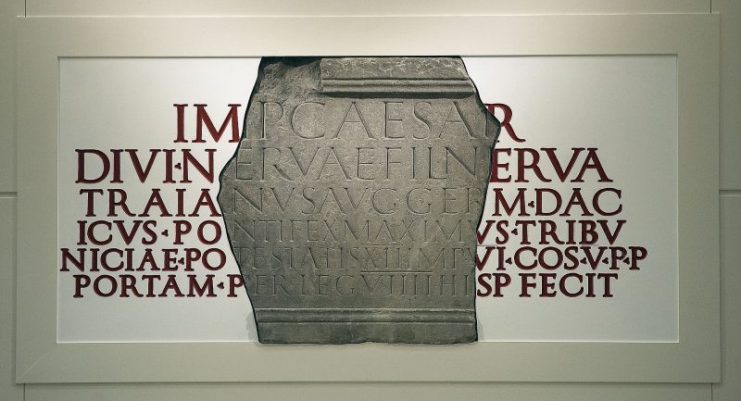

After the successful suppression of the Iceni revolt, the 9th was reinforced and transferred to York, to guard what had become the northernmost border of the Roman Empire. Records show that by 77 AD it was well established in its new base. The last known, recorded activity of the 9th Legion in Britain was the construction of a new and improved stone fortress in York in 108/109 AD.

After that, the 9th Legion simply vanishes from the historical record. An inscription from the reign of the Emperor Marcus Aurelius (161 AD-180 AD) has been discovered which provides a list of all Roman Military units at that time and Legion IX Hispana is conspicuously missing.

What could have happened to the 9th Legion? How could it simply disappear? The fate of the 9th has been the subject of debate for scholars for almost three hundred years.

https://youtu.be/eN1IML5g34I

One of the first historians to consider the fate of the 9th Legion was British antiquarian John Horsley who published Britannia Romana:The Roman Antiquities of Britain in 1732. Horsley was able to identify when the various Legions sent to Britain arrived and left, but noted that there was no obvious record of the 9th leaving. It seemed that this legion had arrived in 43 AD, but hadn’t left, something Horsley found very difficult to explain.

German historian and scholar Theodor Mommsen received the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1902 for his multi-volume A History of Rome. In that book Mommsen claimed that a tribe called the Brigantes had mounted a large-scale attack on the Roman fortress of Eboracum (York) around 117/118 AD and had wiped-out the legion stationed there.

According to Mommsen, the defeat of the 9th legion was one of the things that prompted the Emperor Hadrian to begin the construction of a defensive wall north of York four years later in 122 AD.

For many years, Mommsen’s theory was generally accepted as the most likely explanation of what had happened to the 9th. The dramatic story of the annihilation of a whole legion inspired several fictional works including Rosemary Sutcliff’s popular historical novel The Eagle of the Ninth published in 1954, the 2007 movie The Last Legion and even the tenth series of Doctor Who in 2017 in which an episode titled The Eater of Light featured the 9th Legion being attacked and wiped out by an alien being.

However, in the study of ancient history it often seems that, no sooner has someone provided a believable theory that becomes widely accepted than another historian appears with an equally plausible but completely different theory. So it was with the idea that the 9th legion was wiped out in the north of England.

In the 1990s several items were discovered during archeological excavations at the site of a Roman fortress at Noviomagus Batavorum, present day Nijmegen in Holland. These items included tile stamps and a military medal, all dating from 104-120 AD and bearing the notation ‘LEG HISP IX.’

Other research has also revealed the names of senior officers who served in the 9th but who cannot have occupied these posts earlier than 121 AD. Taken together, these things persuaded most historians that the story presented by Mommsen that the 9th Legion was annihilated in 117/118 AD in Britain cannot be true.

By the late 1990s most people accepted that the 9th Legion probably didn’t disappear until after it had left Britain, perhaps being lost during the Jewish revolt in 132 AD or in a revolt of tribes on the Danube in 162 AD. However, in the early 2000s other historians pointed out that the items recovered from Nijmegen might have another explanation.

It was known that sub-units of the 9th Legion were detached for service elsewhere during the time the main part of the legion was in the north of England. For example, in 83 AD, while the main body of the 9th Legion was engaged in fighting in Britain, records show that a detachment of as many as 1,000 men of the 9th were involved in a battle with the Chatti tribe near Mainz in present-day Germany.

Under the command of Gnaeus Julius Agricola, the 9th took part in fighting in present day Scotland in 82/83 AD, but the Greek military writer Tacticus, who complied histories of many Roman wars, described the 9th at this time as Maxime invalida (the weakest of all), probably due to so many of its troops being detached to other theatres.

The latest thinking is that the artifacts recovered in Holland may show only that a small, detached unit of the 9th Legion was in that area after 120 AD, meaning that it still possible that the main part of the legion had been destroyed earlier during fighting in Britain.

Despite all the debate and the different theories, there is still no certainty about what happened to the 9th Legion. Evidence makes it certain that the men of the 9th were building a stone fortress in York in 109 AD.

Other credible evidence shows that, by the reign of Marcus Aurelius, the 9th was no longer listed as being on the strength of the Roman army. Roman legions did not simply cease to exist so, clearly something very dramatic must have happened between these two dates.

The destruction or disappearance of a whole legion would have been significant and very concerning news in Imperial Rome – the 9th had on its strength around 5,500 men, not including attached auxiliaries. However, to date, no historian has been able to find any contemporary or later mention by any Roman commentator which specifically mentions the fate of the 9th Legion.

Read another story from us: Celtic Warriors Limit Roman Power at Hadrian’s Wall

Was the 9th Legion, one of the oldest units in the Imperial Roman Army, really wiped out in a defeat so complete that no-one survived to report it? Has this major battle been completely missed by every Roman writer and historian? Until someone finds definitive evidence of the fate of the lost legion, it seems likely that what happened to the 9th Legion will remain a mystery as well as a subject for lively debate, speculation and conjecture.