Though long since reduced to ruins, the line of Hadrian’s Wall is still visible through the countryside of northern England, from Bowness on the west coast to Wallsend on the east coast. It remains one of the most impressive and fascinating accomplishments of Rome’s skilled military engineers. Here are some facts you might not know about the Roman Empire’s most northerly line of defence.

Building the Wall

1 Construction of the wall was ordered in AD 122 by Emperor Hadrian, for whom it is named. According to his later biographer, he built the wall to separate the civilised world of the Romans from the barbarians living beyond it.

2 The idea of a defensive line running from east to west across northern Britain was influenced by an existing line of forts , the Stanegate Frontier. But while Hadrian’s Wall to some extent followed this model, it was built further north.

3 The original plans called for the wall to be 10 Roman feet wide – around 3 modern metres – all along its length. But while some parts were built this thick, doing so everywhere proved impractical. In other places, narrower walls 6 or 8 feet thick were built on foundations matching the original measurements. At other points, the original foundations and position were entirely abandoned so that the wall could be built on higher ground.

4 Like many Roman construction projects, Hadrian’s Wall was built by soldiers. The three legions stationed in Britain at the time – II Augusta, VI Victrix and XX Valeria Victrix – built the wall which they would help to defend. As in battle, the unit structure of the legions came in handy, and the work was split into parts that could each be done by a single century of 80 men.

What the Wall was Like

5 The wall was 80 Roman miles long – 117 kilometres or 73 miles in modern measures.

6 It ran along the crests of hills whenever possible, adding to its height. This made it both more imposing and more defensible.

7 Most of the wall was made of stone, but 31 miles of defences at the western end were originally made of weaker stuff, in the form of ramparts made of timber and turf. These were replaced over time, one of the several changes the wall went through in its years of use.

8 The foundations of the wall were cobblestone, even on some stretches where the wall itself was not made of stone.

9 The stone parts of the wall were built around a core of rubble, allowing them to be built thickly at relatively low cost. This was covered in faces of cut stone joined together with lime mortar, for a solid finish.

10 To make the wall even more intimidating it was whitewashed. The white painted stone, therefore, stood out against the surrounding landscape, a clearly manmade feature, and one that the people living to the north could never have imagined building for themselves.

11 We don’t know how tall the wall originally was – too much of its height was lost in later centuries for us to see it at its most intimidating.

12 We also don’t know for certain whether there were battlements and a walkway along the wall for soldiers to patrol and watch for threats to the north. Hadrian’s system along the German frontier used walls without walkways that simply provided a barrier to anyone wanting to pass through, and the same may have applied here. Even so, fortresses and watch towers would have allowed sentries to keep watch to the north.

13 Small forts were built at every Roman mile along the length of the wall. Between each pair of these ‘mile castles’ were two smaller turrets.

14 The ‘mile castles’ varied in design depending on which legion built them. They had an average internal area of around 18 square metres (60 square feet). Each one included a gateway to the north and one facing south, allowing people to travel through the wall at these forts. Each northern gate was topped with a tower for extra defence.

15 Other forts were added over time on or close to the wall, to house the men stationed there.

Life on the Wall

16 Soldiers from all over the empire served on Hadrian’s Wall – a record from an inspection in the 90s AD shows that Dutch and Belgian troops were currently stationed in the region along the line where Hadrian’s Wall would later be built.

17 As at other garrisons, the troops on the wall had a variety of activities to keep them busy. Guard duty and patrols kept an eye on the surrounding area. The base and its equipment had to be cleaned and repaired, including mucking out the latrines. There were regular drills and less regular parades and religious ceremonies for special occasions.

18 Serving on Hadrian’s Wall could be bad for the eyesight of the soldiers serving there – records from one of the fortresses along the wall show that conjunctivitis caused the most visits to the infirmary. Given conditions in the region, it’s hardly surprising – the biting wind whipped into the eyes of the soldiers on watch as they faced north.

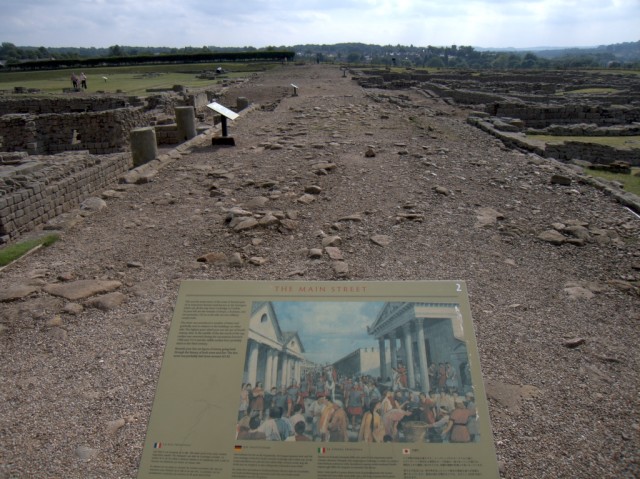

19 The soldiers weren’t alone at the wall. As often happens at military bases, civilian settlements grew up around some of the forts, supplying the needs of the soldiers and making the most of their presence to provide a steady supply of customers and a safe place to live.

20 The presence of the wall severely limited the raiding common between tribes and by enemies on the Roman frontier. No-one mustered an army large enough to assault the wall, and with it in the way mounted raiders could not ride south. This meant that it was harder to take loot home. At most, small bands of warriors on foot would sneak across the wall and carry what they could back to their homes afterwards. It added to the security of the region.