It is difficult to pin many killings directly to Knight and his men, but numerous tax collectors, conscription officers, and Confederate government supporters were killed around Jones County.

The Free State of Jones is shrouded in mystery and legend. Many sources are contradictory and to this day disagreement remains about why Newton Knight founded his own state within the Confederacy.

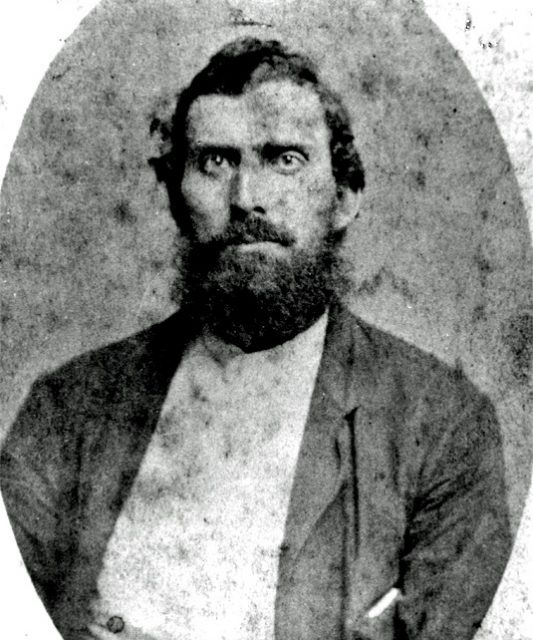

The man himself is a legend. Some describe him as a deserter who only wanted to protect himself from Confederate authorities, while others argue he was a principled Unionist who viewed black people as his equals.

What is the truth behind the pro-Union Free State of Jones that was formed in the heart of the Deep South and the man behind it?

Newton Knight

Knight’s story is uncertain and contradictory from the very start. While historians agree that Knight was born in rural Jones County in Mississippi, his decedents argue whether he was born in 1829 or 1830. Additionally, the 1900 census recorded him as being born in 1837, although many historians suspect he lied during the census to obscure his identity.

It is known that there were no public schools in the county, so he was likely educated at home. Although the extent of his education is unclear, it is likely that it covered little more than basic literacy and farming techniques. His direct family did not own slaves.

Shortly before the American Civil War broke out, Knight and his wife Serena started a small farm. When the war began Newton enlisted in the 8th Mississippi Infantry. In 1862 he joined the 7th Mississippi Infantry after being allowed to return home to attend to his elderly father.

Yet Knight’s views on the war began to change.

It is uncertain why Knight deserted the Confederate army, but there are several elements that likely played a role. The Confederate government began appropriating private property to help the war effort, including Knight’s family horses (a major blow for a small farmer).

It is also possible that his brother-in-law, known only as Morgan, was abusing Newton’s children. Knight was also upset that the “20 Negro Law” was passed, allowing slave owners with more than 20 slaves to avoid Confederate conscription. Class issues clearly played a role in Knight’s disillusionment with the Confederacy.

Rebelling against the rebels

Reports of Knight’s actions after going AWOL are muddled. Some relatives allege that he killed Morgan upon returning home, while also suggesting that Morgan may have been a convicted murderer himself. Regardless, Newton resurfaces after his arrest for desertion in 1863. He was subsequently imprisoned by Confederates and his whole farm was burned to the ground in retaliation.

https://youtu.be/mYpNz7bvB1g

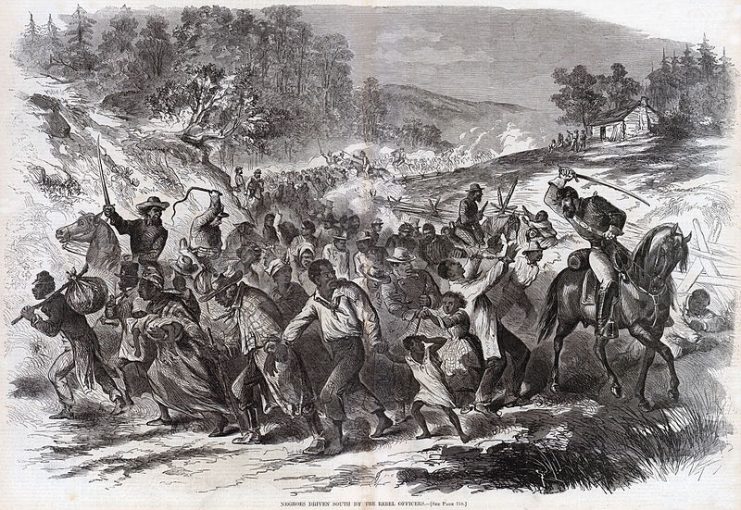

Vicksburg fell in 1863, after which many Confederates in the area began deserting and joined with Knight once he got out of jail. The problem became so bad that Confederate forces had to be redirected to fight the rebels in Jones and surrounding counties.

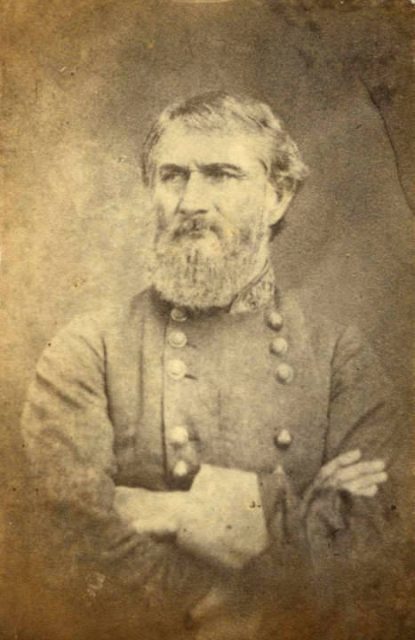

General Braxton Bragg sent Major Amos McLemore to round up Knight and the others as they started raiding farms and even attacking Confederate troops. McLemore was soon killed, allegedly by Knight himself.

By late 1863, Knight was hiding in the Mississippi swamps where he assembled a group of escaped slaves and Confederate deserters. This group became known as the “Knight Brigade”.

It is difficult to pin many killings directly to Knight and his men, but numerous tax collectors, conscription officers, and Confederate government supporters were killed around Jones County during this period. Knight’s men are known to have engaged in skirmishes against Confederate troops attempting to capture them on numerous occasions. On one occasion, Knight and his men captured food supplies during a raid and redistributed it among the locals.

A free state

At this point, Jones County and the surrounding areas were essentially independent of the Confederacy and remained like that for the rest of the war.

One Union scout reported that Knight had 600 men ready to join the Union army when they arrived. Knight himself later claimed that he only had around 125 men active at any one time. However, their loyalty to the Union was clear when they raised the United States’ flag over a county courthouse in Ellisville.

In response, Confederate General Leonidas Polk ordered some of his veteran soldiers to hunt down Knight and his men. The Knight Brigade scattered to continue its guerrilla warfare, but around ten were caught and killed, including two of Knight’s cousins.

Still, local papers reported that the area had “seceded from the Confederacy” and Knight’s men sent a message to General William Sherman pledging their loyalty to the Union. The Free State of Jones didn’t truly had its own government or official leaders, but it never fell back into Confederate hands.

Reconstruction

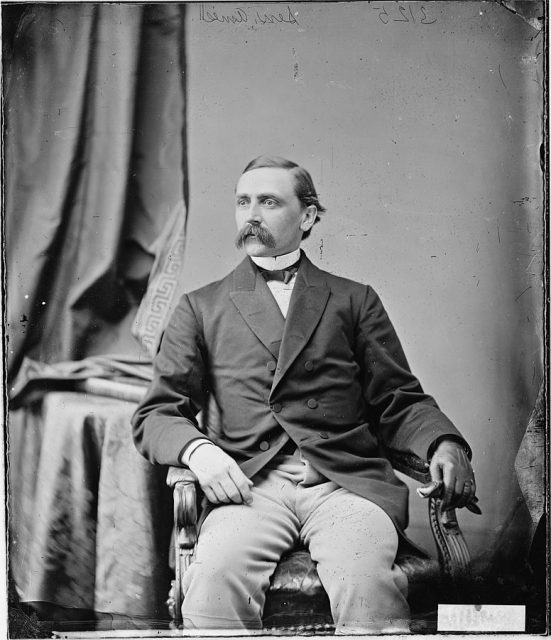

Newton Knight continued supporting the federal government was an avid proponent of Reconstruction after the war. In 1872 Governor Adelbert Ames, the last Reconstruction governor of Mississippi, appointed Knight as a deputy US Marshal.

Meanwhile, in 1875 white supremacist paramilitaries began intimidating black voters and started preparing to take back the state government. Knight was subsequently made a Colonel of the all-black First Infantry Regiment of Jasper County.

However, despite Knight’s efforts Reconstruction came to an end in 1877, and Conservative Democrats took over the governorship. With the new government, Knight left politics.

It was around this time that Knight separated from his wife and married a freed black woman named Rachel. Although this union was illegal since the new state government banned interracial marriage, their marriage continued until Rachel’s death in 1889. The couple had several children who eventually led to several interracial families forming in the county.

Knight passed away on February 16, 1922 at the age of 92. He was buried next to Rachel, something that was illegal under Mississippi law.

Legacy and controversy

To this day, Knight’s descendants continue to reside in the area of Jones County, and many of them are interested in sharing his story with later generations. These stories sometimes contradict each other. These contradictions are often tied directly to race, as Knight’s descendants from his first marriage are white, while those from his second marriage are multi-racial, and those descended from one of his cousins are black.

Some of his living white relatives still denounce him as a traitor to the Confederacy and refuse to communicate with their multi-racial relatives. Yet the rest of the family tends to be supportive of his legacy. His son, Thomas Jefferson Knight, defended him as loyal to the Union and his conscience, and portrayed him as a Robin Hood-esque figure who saved his community by redistributing food during the war.

His multi-racial descendants often faced discrimination under Mississippi laws. Even after generations of marrying white people and some of the family appearing to be and identifying as white, Mississippi’s “one drop rule” ensured that they were discriminated against.

Nathan’s story was recently portrayed in the 2016 film Free State of Jones, and his legacy continues to be shrouded in mystery, contradiction, and controversy.