In the years following World War II, global competition to produce faster and more advanced jet fighters reached new heights. In the midst of this technological race, Swedish aircraft manufacturer Saab took a bold step forward with the development of the J35 Draken during the 1960s. The project centered around an audacious concept—a tailless jet with a distinctive double-delta wing configuration that defied conventional aeronautical design principles.

Despite the technical obstacles, Saab’s engineers displayed remarkable creativity and determination. Through rigorous testing and refinement, they succeeded in bringing the Draken to life—a sleek, agile interceptor that demonstrated exceptional performance and versatility. The aircraft’s success not only validated Saab’s innovative approach but also cemented the Draken’s place as one of the most forward-thinking jet fighters of its era.

Development of the Saab J35 Draken

Amid the Cold War, the Swedish Air Force was determined not to fall behind in the race for cutting-edge jet fighter technology. They envisioned a supersonic interceptor capable of intercepting bombers at high altitudes, prompting the Defence Materiel Administration to lay out stringent requirements for a next-generation aircraft.

Unlike the U.S. Air Force’s Lockheed F-104 Starfighter, the Swedish fighter had to fulfill a unique role—it was designed to operate from reinforced public roads, a strategy born out of Sweden’s need to protect itself against potential nuclear threats during the Cold War. Additionally, it needed to be effective in all weather conditions.

Thus, the Saab J35 Draken, also known as the “Nordic Dragon,” was conceived to meet these high demands.

The Draken’s standout feature was its double-delta wing design, a daring choice that had never been tested in operational aircraft. Though the design posed potential risks, it promised solutions to many of the challenges faced by the Swedish Air Force. The robust delta wing structure provided ample space for fuel storage, which was crucial for long-range missions, although it did create additional drag.

Without the aid of modern tools like computer simulations, Saab’s engineers embarked on a painstaking process of trial and error. Through extensive wind tunnel testing and initial flight trials, they developed a smaller, flyable prototype known as the Saab 210, or “Little Dragon.” The Little Dragon made a successful first flight over Stockholm in January 1952, proving the concept and breathing life into the full-scale J35 Draken project.

Saab J35 Draken specs

Designed for velocity, the Draken’s turbojet engine, equipped with afterburners, propelled it past Mach 2, more than twice the speed of sound. The cockpit offered pilots ample space and outstanding visibility, while state-of-the-art radar and fire-control systems positioned the aircraft at the forefront of contemporary fighter technology. Its fuselage was divided into front and rear sections, each meticulously arranged to house critical avionics and mechanical components.

For armament, the Draken primarily carried up to four AIM-9 Sidewinder missiles mounted on the wings. Additionally, it could deploy rockets and bombs stored internally. Depending on operational requirements, the aircraft could be outfitted with twin 30 mm cannons or external fuel tanks to extend its operational range.

A rather bouncy start

The Saab J35 Draken’s early days in service were anything but easy.

Its double-delta wing design was a groundbreaking concept, but it made the aircraft difficult to control. Landing required pilots to manually stabilize the jet, making every touchdown a high-risk challenge. However, there was an unexpected upside. While struggling to master the aircraft, pilots accidentally discovered a maneuver that no other country had figured out at the time.

Cobra Maneuver

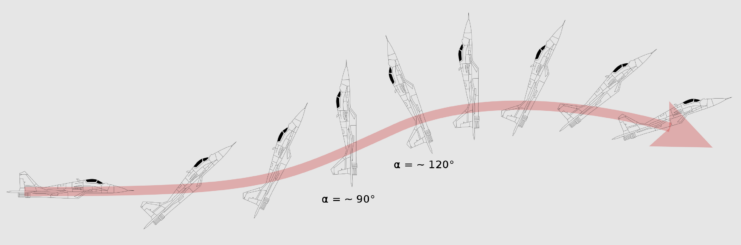

While working to master the tricky J35 Draken, Swedish test pilots discovered an important flying technique called the Cobra Maneuver. When the Draken stalled at high angles of attack and became hard to control, they learned that by quickly lowering the angle of attack, they could break the stall and regain control of the jet.

This clever move essentially turned the Draken into a giant airbrake, allowing it to sharply reduce its speed in a matter of seconds. With its impressive speed, range, and advanced systems, the J35 reshaped the meaning of a “super stall.” The Cobra Maneuver became a daring display of controlled stalling, highlighting the aircraft’s remarkable agility and ability to slow down quickly when needed.

Saab J35 Draken’s legacy

The J35 Draken wasn’t just a high-altitude interceptor—it also demonstrated remarkable agility as a dogfighter. Its sharp maneuverability and blistering speed gave it an edge over many of its contemporaries, making it nearly twice as capable as other single-engine fighters of the same era.

As Saab continued to refine the design, the upgraded J35B variant brought even greater advancements. Equipped with a more powerful engine, an enlarged afterburner, and a reengineered rear fuselage, the aircraft delivered improved performance across the board. Most notably, it was integrated into Sweden’s sophisticated STRIL 60 air defense network, allowing the Draken to operate seamlessly within a cutting-edge, radar-guided command system—ahead of its time in both concept and execution.

More from us: Why Did a Test Pilot Wear a Gorilla Mask In Flight?

While the Cobra Maneuver is often linked with modern Russian jets such as the Sukhoi Su-27 and Mikoyan MiG-29, its origins trace back to an unexpected source. The pioneering Saab J35 Draken was the first aircraft to unintentionally perform the maneuver—long before it became a deliberate display of aerodynamic mastery.

During flight testing, pilots discovered that the Draken’s unique double-delta wing configuration allowed it to momentarily pitch its nose to an extreme angle of attack without stalling—a phenomenon that would later be refined into the now-famous Cobra Maneuver. This accidental breakthrough cemented the Draken’s place in aviation history as not only a formidable fighter but also a trailblazer in aerodynamic innovation.