Ambroise Paré was a French military surgeon and pioneer of many medical techniques. He was skeptical about the accepted medical wisdom of his day as much of it was based on folklore and tradition.

Paré developed his own scientific methods based on testing and observation to improve the care of his patients, both on the battlefield and at the Royal Court of France where he worked for much of his career.

He was born in Bourg-Hersent in northwest France in 1510. His older brother was a surgeon and the young Paré often watched his brother at work. It is not surprising then that Paré later went to Paris to become his brother’s apprentice before training more formally at the Hôtel-Dieu de Paris, which had been founded in the 7th century and was the oldest hospital in France.

The profession of surgeon or “barber-surgeon” was quite distinct from that of a doctor. During this period doctors did not perform surgery.

That was left to those who were skilled with the knife and the barber-surgeons’ tasks included not only cutting beards and letting blood but also surgical procedures ranging from basic wound treatment to amputations.

A scientific approach to military medicine

Paré worked for many years treating wounded soldiers in the battlefield and it was there that he developed his experimental approach. He compared different treatments used to heal the wounds of injured soldiers.

One group’s wounds were treated in the usual way which involved boiling elder oil and cauterization. For another group, he used an ointment made from rose oil, egg yolk, and turpentine. Paré noticed that not only did the cauterized group suffer more pain while receiving treatment, but also that their wounds did not heal as well as those of the group treated with the ointment.

Paré also reduced the use of cauterization in amputation where it was traditionally used to seal the wound to prevent blood loss. Instead, Paré encouraged the use of ligatures around the arteries to prevent bleeding.

This was not without risks as little was understood about the need for antiseptic surgery and the ligatures were often a source of infection. However, it was better than the standard procedure of sealing the wound with a red hot iron which often resulted in the patient dying of shock due to the pain.

On another occasion, Paré saved a wounded soldier who needed a bullet removed. The surgeon attending the soldier couldn’t find the bullet, so Paré suggested asking the soldier to stand exactly as he was when he was shot. He was then able to work out the likely position of the bullet. It was found and removed. Although simple, it was typical of Paré’s scientific and logical approach.

As a military surgeon serving on the battlefield, amputations were a major part of his work as there was often not much chance of saving the limb given the circumstances and limited medical knowledge of the time. This naturally led Paré to investigate prosthetics, designing prosthetic limbs as well as artificial eyes using enameled porcelain, silver, and gold.

Many of his ideas seemed unusual at the time, but some have since been backed up by modern science. Paré was the first person to understand the phenomena of phantom limbs, in which an amputee still “feels” pain or other sensations in the limb that has been amputated. At the time the pain was believed to be in the remaining part of the amputated limb, but this did not fit with the patients’ description of how they felt the pain.

Paré, who had also carried out neurosurgery, was the first to suggest that the feeling actually had to do with what was going on in a patient’s brain, not the residual limb.

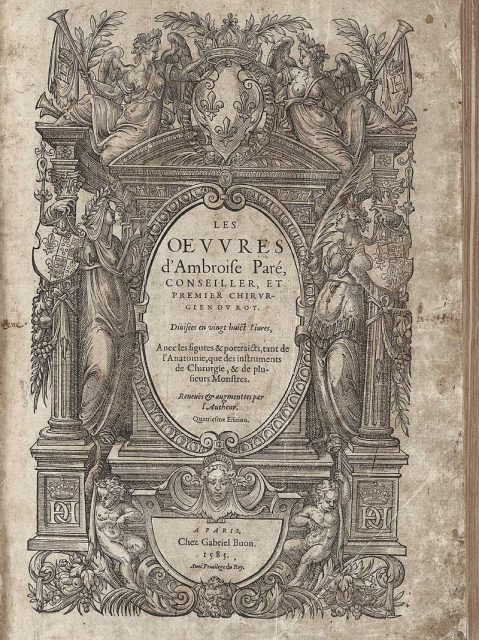

Paré wrote about his new methods in his book The Method of Curing Wounds Caused by Arquebus and Firearms which was published in 1545.

One of Paré’s more dramatic experiments took place away from the battlefield when he was working at the Royal Court. At the time many people believed that bezoar stones could cure any kind of poisoning. Bezoar stones are compact masses—such as gallstones and kidney stones—found in the digestive tracts of humans and animals, and they were kept and either saved or sold as a cure.

In 1567 Pave set out to disprove this myth. There was a cook at the court who had been condemned to death for stealing. Paré offered him a gamble which could lead to either a more painful death or freedom. The cook agreed to take a deadly poison and then be treated with bezoars. According to the deal, if the stones cured him he would be set free.

However, as Paré’s theory was correct, the stones failed to cure the cook who died a painful death, probably much worse than the gallows.

Royal Court Surgeon

As well as serving on the battlefield, from 1552 until his death in 1590 Paré worked for the French Court and served four consecutive kings starting with Henry II. During his service, his skills were called upon when Henry suffered a blow to the head during a jousting tournament. But even Paré could not save the king. Despite this, he was kept on and served Kings Francis II, Charles IX and finally Henry III.

Although it was Paré’s job to save the king’s life, there was an occasion when it was the king who saved his life. It is very likely that Paré would have been killed during the St Bartholomew’s Day Massacre on 24 August 1572 if King Charles hadn’t saved him by locking him in a closet.

The massacre was carried out by Catholic mobs again Huguenots. Paré was of Huguenot descent, although he appeared to have lived outwardly as a Catholic. This might only have been to protect himself during the religious war in France.

Paré lived a long life. He died of natural causes at the age of 80 and left behind an important legacy which he recorded in his books published both in French and Latin. He is remembered today as the father of military surgery.