Not only did the Pearl Harbor attack of December 7th, 1941 deal a devastating blow to the United States’ Navy and draw the nation into World War II, but it also gave the Japanese Imperial Navy some six months to further their control of the Pacific without U.S. interference. This was, of course, the plan.

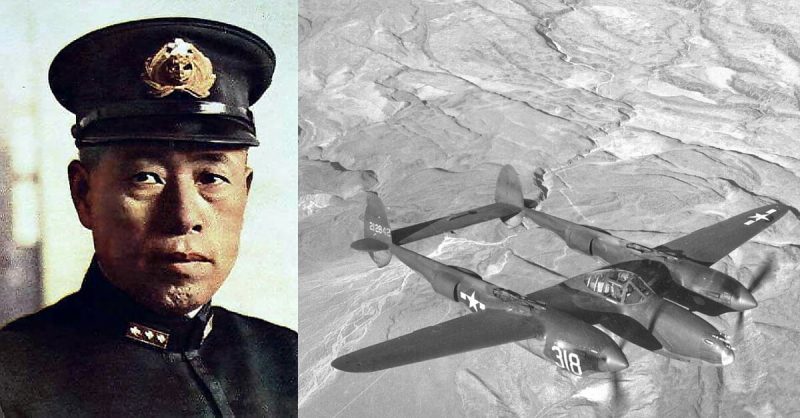

Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto was the architect of the Pearl Harbor pre-emptive assault. So when U.S. Naval Intelligence initiative code-named “Magic” intercepted communications that Yamamoto would be doing an inspection tour of his forces on the Solomon Islands, the U.S. seized the opportunity for vengeance.

“Get Yamamoto,” commanded President Franklin D. Roosevelt. Operation Vengeance was a go.

Magic had long since broken the cipher of the Japanese navy, JN-25D, which had brought results in their fight in the Pacific. This was through the efforts of Navy cryptographers and Japanese-Americans translating the complicated and very context-based language.

On April 14, 1943, messages detailing Yamamoto’s tour of the Solomon Islands were intercepted.

Eighteen P-38G Lightnings of the 339th Fighter Squadron, 347th Fighter group, were chosen as the aircraft for the mission. They would be flying out of Guadalcanal, South and West of the Solomon Islands and rounding back NorthEast again to intercept Yamamoto flying from Rabaul to Bougainville.

The mission would be about a 1,000 mile round trip with more fuel expended in the firefight with the two Mitsubishi G4M Betty bombers and six Mitsubishi A6M Zero Navy fighters. Only the P-38Gs, equipped with drop tanks with extra fuel could make the trip.

The mission would have to be flown in radio silence, to avoid detection. Major John W. Mitchell, therefore, requested that each plane was outfitted with a ship’s compass to navigate. At 7:25 in the morning on April 18, the Lightnings took off for two hours of silent flight, 50 feet above the waves to avoid radar detection.

Odd as it may sound, the man they were going to shoot down was one of Japan’s most outspoken opponents of war with the U.S.

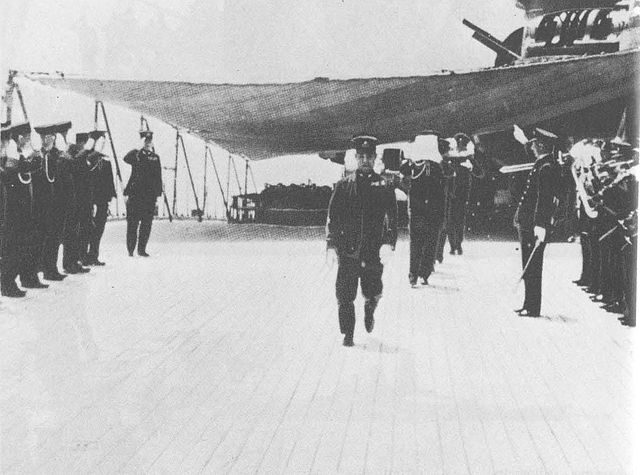

In fact, Yamamoto had spent many years in the country he was now fighting, including for two years as a naval attache in Washington, from 1926-28. He was critical of Japan’s ongoing war with China and with the drive to engage in combat with the U.S., a stance that led to powerful pro-war interests in Japan calling for his head. Admiral Yonai Mitsumasa, in an effort to save Yamamoto’s life, promoted him to commander-in-chief of the Combined Fleet and sent him out to sea in 1939.

Yamamoto had also warned the Japanese government that war with the U.S. could only be successful for six months to a year before the tides turned, but he was given no choice.

He planned the Pearl Harbor attack to bide time for Japan to wrest control of the Pacific before drawing the U.S. Navy into a decisive battle that would force them to negotiate for peace.

Yamamoto convinced the Naval General Staff to move for this great battle after the Doolittle Raid of April 1942 struck Tokyo. He sailed for Midway Island with four aircraft carriers. However, by this point, the U.S. had broken the Japanese cipher and, with a force of three aircraft carriers, counter-attacked and sunk all four of the Japanese ships. The tides in the Pacific had already taken a massive turn.

At the time Operation Vengeance was set in motion, Yamamoto had been trying, and slowly failing, to control the Solomon Islands. After landing troops on Guadalcanal, he was met by US forces landing in August 1942 in what would be a long and very costly battle, ending in a U.S. victory in February the next year. Thus, in April 1943, the inspection tour of forces on the Solomon Islands was planned to invoke a very much needed morale boost.

At 9:34 a.m. on April 18th, after two hours of navigating by flight plan and, as Mitchell puts it, “dead reckoning,” the 18 P-38Gs spotted Yamamoto’s transport and escorts. The planes jettisoned their extra fuel tanks and tore into a power climb to engage the enemy.

The “killer flight” group, Lt. Thomas G. Lanphier, Jr., Lt. Rex T. Barber, Lt. Besby F. Holmes, and Lt. Raymond K. Hine headed for the bombers.

Holmes’ auxiliary fuel tanks didn’t detach, and he had to draw back. Lanphier turned to engage the escort Zero fighters diving to defend Yamamoto and his staff while Barber chased down the bombers. As Barber came around, he fired his .50-caliber machine guns into the right engine, fuselage, and tail assembly of the bomber Yamamoto was flying in, which crashed into the jungle. Barber also hit the second bomber, which crash-landed in the water. Chief of Staff Vice Admiral Matome Ugaki and two others in the second bomber survived.

According to the search and rescue party who found Yamamoto, his body had been thrown from the plane, still in his seat, his hand on his katana and two bullet holes in his shoulder and head.

Operation Vengeance was the longest fighter-intercept mission of the war. Lt. Hine lost his life when his plane was shot down by a Japanese Zero. It is well agreed, now, that Lt. Barber is credited with shooting down Yamamoto, but Lanphier claimed it was he until the day he died. This discrepancy was fought over between the two for many years.

Forensic evidence of bullet trajectory in the wreckage of Yamamoto’s downed bomber concurs with Barber’s account.