71 years ago today was the beginning of the Great Escape. Below is an excellent article by Rob Davis, Telford, Shropshire from the UK. This is one of the most in-depth articles that you really do need to read and share – a great monument to the 50 PoW’s that were murdered.

Prisoners Of War

Allied aircrew who were shot down and survived during World War II were incarcerated after interrogation in Air Force Prisoner of War camps run by the Luftwaffe, called Stalag Luft, short for Stammlager Luft or Permanent Camps for Airmen. Stalag Luft III was situated in Sagan, 100 miles south-east of Berlin, now called Zagan, in Silesia. At the time of the escape it was part of Germany, but is now in Poland. It was opened in Spring 1942 with the first prisoners arriving in April of that year, and was just one of a network of Air Force only PoW camps. The Germans treated captured Fleet Air Arm aircrew as Air Force and put them all together. There is no obvious reason for the occasional presence of a non-airman in the camps, although one possibility is that the captors would be able to spot “important” non-Air Force uniformed prisoners more readily.

RAF personnel captured whilst serving in the Air/Sea Rescue branch are also known to have been kept as PoWs at Air Force camps, including at Stalag Luft III, being treated as if they were downed aircrew.

Two main compounds were established, ‘East’ and ‘North’. Despite starting out as an officers-only camp, it was not referred to as Oflag (Offizier Lager) like some other officer-only camps. The Luftwaffe seemed to have their own nomenclature, and later camp expansions added the ‘Centre’ compound for NCOs. As the number of American airmen prisoners gradually increased, the ‘South’ compound was added to house them.

A large contingent of PoWs sent to Sagan at the end of April 1943 had come from the camp at Schubin. It was at Sagan, that the famous “Wooden Horse” escape occurred on the night of October 29/30, 1943. Three PoWs (Oliver Philpot, Eric Williams and R Michael Codner) having concealed themselves in a vaulting horse, had spent months digging a tunnel through which they escaped and eventually reached England via neutral Sweden.

David Harris adds [January 2013] : “Michael Codner who escaped in the “Wooden Horse” escape left one son, Peter a barrister with whom I worked until he was disabled by a stroke. When last I spoke to him a couple of years ago he was living in Devizes, Wilts. Peter had a reputation as one of th most aggressive barristers in England and was well known to the Court of Appeal. He is a bit of a West Country legend among lawyers and had enormous energy and imagination becoming well known for taking difficult cases that no one else would even touch and winning as if by magic. He said people who knew his father said he was very much like him and he considered himself, and I think justifiably so, that he had a bit of an “escapologist” in him, getting out of difficult legal situations. He never met his father who was shot in the Malaysian uprising when Peter was 3 years old.”

I was able to visit Zagan in May 2007 and there are modern photographs of the site here.

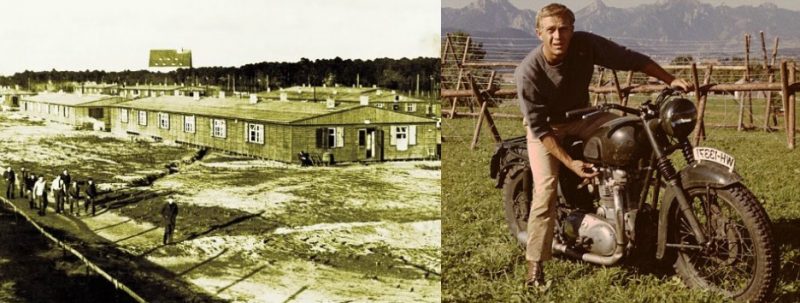

The 1963 film, starring Richard Attenborough, Steve McQueen etc is detailed here.

This is the story of one Officer – “The Man Who Traded Places”

Conditions and Kommandants

It must be made clear that the German Luftwaffe, who were responsible for Air Force prisoners of war, maintained a degree of professional respect for fellow flyers, and the general attitude of the camp security officers and guards should not be confused with the SS or Gestapo. The Luftwaffe treated the PoWs well, despite an erratic and inconsistent supply of food.

It must be made clear that the German Luftwaffe, who were responsible for Air Force prisoners of war, maintained a degree of professional respect for fellow flyers, and the general attitude of the camp security officers and guards should not be confused with the SS or Gestapo. The Luftwaffe treated the PoWs well, despite an erratic and inconsistent supply of food.

Prisoners were handled quite fairly within the Geneva Convention, and the Kommandant, Oberst (Colonel) Friedrich-Wilhelm von Lindeiner-Wildau (left), was a professional and honourable soldier who won the respect of the senior prisoners.

He was 61 when the camp opened in May 1942, a capable, educated man who spoke good English. Having joined the army in 1908, and after being wounded three times in WW1, winning two Iron Cross awards, he left in 1919 and worked in several civilian posts, meanwhile marrying a Dutch baroness, whilst trying to steer clear of Nazi politics. Eventually he joined the Luftwaffe (the least Nazified of the three German forces) in 1937 as one of Goering’s personal staff. Refused retirement, he found himself posted as Sagan Kommandant, with Major Gustav Simoleit as deputy. The first Kommandant, Colonel Stephani, had been quickly replaced when found to be unsuited to the task.

Security was strict, but life was not intolerable, except for those for whom escape was a restless itch… this was reckoned to be just 25 percent of the camp population, and only 5% of those were considered to be dedicated escapers. The others would, however, work in support of any escape attempts.

After several major expansions, Luft III eventually grew to hold 10,000 PoWs; it had a size of 59 acres, with 5 miles of perimeter fencing. The administrative area, a generally off-limits zone to PoWs, was known as the ‘Vorlager’ and here was the hospital, Red Cross storage hut and provision for keeping coal, plus the bath-house.

Food, Letters and Parcels

Had it not been for food parcels sent in via the International Red Cross (who also made inspection visits), food would have been a serious problem in all PoW camps. Issued with little more than starvation rations, food parcels sent by relatives, despite being regularly stolen by the many hands through which they passed, were essential. It should be borne in mind that the guards themselves were not much better off than the prisoners, in terms of food. On average, one parcel per week per man was provided.

The rule in most of the camps was that both “individual” (for a named person, sent and paid for by relatives and containing a mixture of goods) and “bulk” parcels (for general distribution, sent and paid for by the International Red Cross, and containing a supply of a single item) were pooled. Thus, replacement clothing, shaving and washing kit, coffee, tea, tinned meat, jam, sugar and essentials were distributed equally.

The rule in most of the camps was that both “individual” (for a named person, sent and paid for by relatives and containing a mixture of goods) and “bulk” parcels (for general distribution, sent and paid for by the International Red Cross, and containing a supply of a single item) were pooled. Thus, replacement clothing, shaving and washing kit, coffee, tea, tinned meat, jam, sugar and essentials were distributed equally.

In PoW camps, captured officers were paid an equivalent of their pay in “lagergeld” or internal camp currency, and could buy items such as musical instruments and what few everyday goods which were available. Captured NCOs did not receive any such allowance, but the officers regularly pooled lagergeld from their own pay, and transferred these to the NCOs’ compound. It was strictly forbidden to be in possession of real German currency, a vital escape aid. At Luft III, all lagergeld was pooled for communal purchases of what items were made available by the German administration.

An internal official method of collective bargaining and bartering called “Foodacco” was set up, allowing PoWs to market any surplus food or desirable item, for “points” which could be “spent” on other items, amongst themselves. Great trouble was taken in food preparation, with special occasions such as a birthday or Christmas requiring months of hoarding. PoWs usually banded together in groups of 8 men for cooking and messing purposes, and such groups usually became very close-knit.

The recommended intake for a normal healthy active man is 3,000 calories; German rations allowed between 1,500 and 1,900. It was a case of the issued official rations providing prolonged and unpleasant starvation and only the Red Cross food parcels saved the day.

Letters were censored both at the sending and receiving ends. PoWs were not restricted in how many they could receive, but were only allowed to send three letters and four postcards every month. Letters averaged three weeks to arrive from Canada, four from the UK and five from the USA, and were censored by Hauptmann (Captain) von Massow and his team.

Clothing was often a problem, items of civilian nature being strictly forbidden and military uniform often being cobbled together from whatever was available, regardless of branch. Thus it was not unusual to see officers of any rank in RAF battledress top, Army trousers, and whatever footwear was to hand. Most men made every attempt to maintain a military bearing, ensuring that their rank and flying badges were correct no matter what they were attached to! Any officer who had hidden a genuine civilian item of clothing took great care to keep it safe.

It was absolutely vital to carry aircrew badges and brevets in a secret place whilst escaping, in order to prove that an escapee was not a spy. The Geneva Convention dictated that a serviceman should always wear uniform, or be shot as a spy. Being able to produce evidence of being an escaped PoW was essential. The Germans issued each captive with an official PoW identity disc which could also be used to establish a man’s genuine identity.

Newcomers to the camp had to be personally vouched for by two existing PoWs who knew them by sight. As the numbers of airmen increased, this became essential as it was not unknown for the Germans to introduce infiltrators in an attempt to spy on camp operations and escape attempts. Such infiltrators were known as “stool pigeons”. Any newcomer who could not summon two men who knew him had to suffer the indignity of a heavy interrogation by senior officer PoWs. Also, he was assigned a rota of men who had to escort him at all times, until he was deemed to be genuine. Any stool pigeons were quickly discovered and there is no evidence to suggest that infiltrators operated successfully at Luft III.

One newcomer was given the standard advice to “completely ignore anything you see which is out of the ordinary” and having been vouched for, left the hut where the interview had been held, jumped down the steps outside and promptly collapsed up to his waist in a tunnel.

Several PoWs established means of exchanging coded messages with their relatives, via the Red Cross mail system. Such letters, which were heavily censored by the Germans, were invariably weeks in transit, but provided valuable information to the War Office. This coding was usually a pre-arranged method agreed between an airman and his wife, girlfriend or relative, such as taking every 9th word, or similar method

The Escape Committee

At Luft III arrived some of the finest escape artists in the Allied Air Forces. Squadron Leader (S/L) Roger J Bushell, CO of No 92 Squadron, shot down 23rd May 1940, Spitfire I N3194, during the Battle of France. On a previous escape he had been hiding in Prague and was caught about the time of the Heydrich assassination in mid 1942. The family hiding him were all executed by the Gestapo and Jack Zafouk (311 Sqdn, shot down 16/17 July 1941, Wellington IC R1718 KX:N) his Czech co-escaper, was eventually purged to Colditz Castle. Bushell developed a cold unyielding hatred for the enemy but failed, however, to distinguish between the Gestapo and the far better type represented by the Camp Kommandant.

Bushell, who had became engaged shortly before the war started, may well have had his determination to disrupt the enemy steeled by receiving a “Dear John” letter from his fiancée, just as plans for the mass tunnel escapes were starting in Spring 1943, some three years after he was shot down and taken prisoner. The sender of the letter informed Bushell that she was marrying another man.

At the time of the Wooden Horse escape in October 1943 the SBO (Senior British Officer) was Group Captain (G/C) A H Willetts (7 Sqdn, shot down 23/24 August 1943, Stirling JA678) . Later a more senior officer, G/C Harry “Wings” Day (left, IWM) (57 Sqdn, shot down 13-Oct-39, Blenheim I, L1138), took charge. Wings Day was later succeeded by another more senior officer, G/C Herbert M Massey (7 Sqdn, shot down 1/2-Jun-1942, Stirling I, N3750 MG:D) a rugged veteran WW1 pilot, and in October 1942 Wings Day was sent to Offizierlager (Oflag, or Officer Camp) XXIB.

At the time of the Wooden Horse escape in October 1943 the SBO (Senior British Officer) was Group Captain (G/C) A H Willetts (7 Sqdn, shot down 23/24 August 1943, Stirling JA678) . Later a more senior officer, G/C Harry “Wings” Day (left, IWM) (57 Sqdn, shot down 13-Oct-39, Blenheim I, L1138), took charge. Wings Day was later succeeded by another more senior officer, G/C Herbert M Massey (7 Sqdn, shot down 1/2-Jun-1942, Stirling I, N3750 MG:D) a rugged veteran WW1 pilot, and in October 1942 Wings Day was sent to Offizierlager (Oflag, or Officer Camp) XXIB.

Contrary to popular belief, there was no duty or orders to escape imposed on the PoWs and the majority were content to exist in the relative comforts of the camp. Bearing in mind that many had traumatic experiences in being shot down, it is easy to understand why the ‘stayers’ regarded the ‘escapers’ with disdain, especially when failed escape attempts resulted in the withdrawal of privileges. Despite the formidable obstacles to reaching neutral or friendly territory and making a ‘home run’, many of the ‘escapers’ regarded escaping as a game or as a sport, with even a day outside the wire affording ‘fresh air’ and a break from the routine of PoW life.

The SBO quickly realised that all escape attempts had to be properly vetted and organised, or a free-for-all situation would emerge. Bushell was appointed to mastermind the Luft III Escape Organisation, together with an executive committee of Flying Officer (F/O) Wally Floody (J5481; 401 Sqdn RCAF, shot down 28-Oct-41, Spitfire V W3964), Peter ‘Hornblower’ Fanshawe RN (803 Sqdn Fleet Air Arm, shot down in a Blackburn Skua, possibly L2991:7A) and Flight Lieutenant (F/L) George Harsh (102 Sqdn, shot down 5/6-Oct-1942, Halifax II, W7824).

Bushell collected the most skilled forgers, tailors, tunnel engineers and surveillance experts and announced his intention to put 250 men outside the wire. This would cause a tremendous problem and force the enemy to divert men and resources to round up the escapers. His idea was not so much to return escapers to the UK but mainly to cause a giant internal problem for the German administration. He went about this task with a typical single-minded determinedness, despite having been officially warned that his next escape and recapture would result in him being shot.

According to the Geneva Convention, an international agreement which governed the treatment of captured enemy personnel, the maximum punishment for escaping was 28 days’ solitary confinement. Contact with others in the camp was restricted to the padre, although short daily exercise breaks were usually allowed, under close supervision.

According to the Geneva Convention, an international agreement which governed the treatment of captured enemy personnel, the maximum punishment for escaping was 28 days’ solitary confinement. Contact with others in the camp was restricted to the padre, although short daily exercise breaks were usually allowed, under close supervision.

The photo opposite shows all that remains of the ‘Cooler’ or solitary confinement block, which is adjacent to the tunnel line for ‘Harry’. The underground cells are filled in and only the shape of the above-ground walls can be found. Curiously, the Luftwaffe also referred to this solitary confinement area as ‘the Cooler’.

Listen for the ghostly sound of baseballs bouncing off the wall … can you imagine being subjected to 28 days of that coming from the bloke in the next cell? It’d drive you crazy!

Key Personnel

Tunnel engineering was in the expert hands of Floody, a Canadian Spitfire pilot and prewar mining engineer. The original ‘Tunnel King’, he masterminded the construction of all three tunnels, aided by F/L R. G. “Crump” Ker-Ramsey (Fighter Interception Unit, shot down on a night patrol 13/14-Sep-1940, Blenheim IVF Z5721), Henry “Johnny” Marshall, Fanshawe, and a host of others. The dapper Rhodesian Johnny Travis and his team of manufacturers made escape kit such as compasses from fragments of broken Bakelite gramophone records, melted and shaped and incorporating a tiny needle made from slivers of magnetised razor blades. Stamped on the underside was ‘Made in Stalag Luft III – Patent Pending’.

F/L Des Plunkett (218 Sqdn, shot down 20/21-6-1942, Stirling I, W7530 HA:Q) described as “a nuggety little man with a fierce moustache” and his team assumed responsibility for map making. Real ID papers and passes were obtained by bribery or theft from the guards and copied by F/L ‘Tim’ Walenn and his forgers. These two departments were known as “Dean and Dawson” after a well-known firm of travel agents. Service uniforms were carefully recut by Tommy Guest and his men, who also produced workmens’ clothes and other ‘civilian’ attire. These were often hidden in spaces created by ace carpenter Pilot Officer (P/O) “Digger” Macintosh (12 Sqdn, shot down 12-May-1940, Battle I, L5439 PH:N).

A surprising number of guards proved co-operative in supplying railway timetables, maps, and the bewildering number of official papers required for escapers. One tiny mistake in forgery, or one missing document would immediately betray the holder, a problem complicated by the fact that the official stamps and appearance of the various papers were changed regularly by the Germans. It was necessary to obtain details of the lie of the land directly outside the camp, and especially ascertain details of train movements in the busy local station. Arriving PoWs were brought in by both rail and road transport.

As well as various assistance covertly given by anti-Nazi guards, bribery by cigarettes, coffee or chocolate usually worked. In one case, a less than intelligent guard provided key information for which he was paid in chocolate. The prisoner asked him to sign a receipt, explaining that it was necessary to account for the chocolate with the others in his mess group. The guard obliged, and was soon blackmailed into bringing in a camera and film, Bushell being quite ruthless in exploiting such opportunities.

Forged papers included Dienstausweise (a brown card printed on buckram, giving permission to be on Wehrmacht property), Urlaubscheine (a yellow form used as a leave-chit for foreign workers), Ruckkehrscheine (a pink form for foreign workers returning home), Kennkarte (a light grey general identity card), Sichtvermark (visa), Ausweise and Vorlaufweise (pass and temporary pass). Many of these were as complex as banknotes and required weeks of work to reproduce.

F/Lt Alex Cassie, a 77 Sqdn pilot who was shot down shot whilst on loan to Coastal Command and who was instrumental in the production of forged papers, died on April 5th 2012. Daily Telegraph obituary.

Guards, Goons and Ferrets

Germans were universally known as “Goons”, a nickname which puzzled them. (When asked, a captured officer said that it stood for “German officer or Non-Com”.) The tall sentry watch platforms which mounted searchlights and machine-guns were therefore “Goon Boxes”, and annoying the guards was “Goon Baiting”. Whilst the guards were not the cream of the Luftwaffe, they unhesitatingly shot first and asked questions afterwards if any prisoner was rash enough to stray over the knee-high warning wire, and then fail to surrender if challenged. Some were undoubtedly trigger-happy and records at Kew hold correspondence from the SBO to the Kommandant reporting cases of unnecessary use of firearms.

GOON BOX (watercolour by Geoffrey Willatt and reproduced from his book BOMBS AND BARBED WIRE, ISBN 1-898594-16-3 Parapress Ltd) by kind permission of the artist)

GOON BOX (watercolour by Geoffrey Willatt and reproduced from his book BOMBS AND BARBED WIRE, ISBN 1-898594-16-3 Parapress Ltd) by kind permission of the artist)

The German guards specialising in escape detection were known as ‘Ferrets’ and dressed in disinctive blue overalls, could enter the compound at any time and search any hut without warning. Equipped with metal probes, they searched for the bright yellow sand indicating that a tunnel was in progress, or an English-speaking ferret would lie concealed under a hut listening for careless talk. Their most active, unpredictable and generally dangerous member, Gefreiter (Corporal) Greise, was known as ‘Rubberneck’.

From documents held at the Public Records Office, Kew, London, there is evidence to suggest that when a tunnel was detected by the guards or ferrets, it was allowed to continue without intervention until it appeared to be near completion. Then, the ferrets would pounce, driving heavy trucks around the compound to collapse the tunnels and galleries.

Internal security was put into the capable hands of F/L George R Harsh (102 Sqdn, shot down 5/6-Oct-1942, Halifax II W7824) an American (with an extremely chequered personal history) serving with the RCAF. A rota of officers logged every guard or ferret entering the compound using what was called the “Duty Pilot” system, and Germans were tailed everywhere until they were logged out. An elaborate system of inconspicuous signals was put in place, warning those PoWs engaged on nefarious activities, and giving them time to either mask their activities with innocent-looking hobbies or completely conceal their illicit work. Unable to effectively combat the “Duty Pilot” system, the Germans allowed it to continue, and on one occasion used the log made by F/O George Sweanor to bring charges against two of their own men who had slunk off duty some hours before they should have done. George adds “One hot summer day in 1944, I was walking across our sandy POW compound with Luftwaffe Hauptmann Hans Pieber who spotted a snotty handkerchief discarded on the sand. Criticising such waste, he picked it up, remarking that, if none of us wanted it, he could wash it and use it.”

Pieber was an Austrian, vehemently opposed to Hitler. He is reported to have treated the PoWs sympatherically and to have supplied them with innocent items and on one occasion brought them Pilot’s Notes for the Me109 and Dornier X aircraft.

F/O Geoffrey Willatt (106 Sqdn, shot down 5-Sep-43, Lancaster III DV182) said “I did many hours as ‘Duty Pilot’ identifying guards and ferrets as they came in the main gate (the only entrance) and putting up a signal, to warn other watchers round the camp – the signal comprised an empty tin in a certain position on a nearby rubbish heap. I was in fact accosted by von Lindeiner who saluted me as he always did, to know why I was out in the freezing cold. I said it was for fresh air and exercise and gave a false name and number. I never heard any more.”

A Warm Day At Luft III, Sagan

(watercolour by Geoffrey Willatt and reproduced from his book BOMBS AND BARBED WIRE, ISBN 1-898594-16-3 Parapress Ltd, by kind permission of the artist).

The Tunnels : ‘Tom’, ‘Dick’ and ‘Harry’

The tunnel entrances were masterpieces of deception. All barrack huts were elevated from the ground but each had stoves set on a brick and concrete plinth. ‘Tom’ (the 98th tunnel to be discovered at Luft III) in Hut 123 and ‘Harry’ in Hut 104 both exited through the centre of these pierced foundations. The entrance to ‘Dick’ is still there – concealed in a drain on the floor of the shower room in Hut 122, and when closed and sealed was under several feet of water. The Germans never found it and it probably still contains much contraband and escape material. A 1993 television-based excavation discovered the entrance and evidence of its curious history.

Sudden pounces by the ferrets were a constant nightmare and precision practice was required by the distraction and camouflage teams. In one close shave, F/L Pat Langford (16 OTU, shot down 28/29-7-1942, Wellington IC, R1450), replaced and fully camouflaged Harry’s trapdoor in twenty seconds, leaving no sign of a tunnel entrance. German security was headed byHauptmann (Captain) Broili and Oberfeldwebel (Warrant Officer) Hermann Glemnitz. The latter, aged 44 (in 1943) and with a good sense of humour, was usually referred to as “that idiot, Glemnitz” was both feared and respected by the prisoners as a dedicated discoverer of escape plots.

Jerry Sage described Glemnitz as having “… the build of a square-shouldered light-heavyweight boxer … the most efficient security man I met in Germany … with a sense of humour, not a bully.” After the war, Glemnitz was discovered living in West Berlin and was flown to the 1965 PoW Reunion in Dayton, Ohio and the 1970 event in Toronto, Canada. On arrival in Toronto, he declared “I am here to make sure that you people aren’t trying to tunnel out of Toronto”.

Sand dispersal was effected by ‘Penguins‘, prisoners filling long thin bags which were slipped inside their trousers and walking about the compound, losing the sand from the bottom of the bags. One penguin was careless and the ferrets spotted him trailing sand; they then knew a tunnel was in progress, but they did not pounce, wanting to find out where it originated.

Tunnelling was dangerous – both below ground and above it. The sand was treacherous, and would come crashing down with only the ghost of a warning. Many diggers had only time to protect their heads with their arms as the roof suddenly caved in, and hope that their No.2 could dig them out. No-one was killed, but several were forced to take days off after almost being suffocated. A fall left a large dome above the working face, and after clearing up, the damaged roof was shored and the sand packed back above it. The diggers found that sand dug out occupied thirty percent as much space again as it did normally, placing extra burdens on the disposal teams.

4,000 bed boards were removed to form the shoring, and prisoners became used to sleeping on the barest of supports – often a string semi-hammock, with only two or three real bed boards. The tunnel size was therefore dictated by the width of the boards, almost exactly two feet square, allowing a little for the alignment of the wood at each corner of the square.

Closed down over Christmas 1943, tunnelling was resumed in early January 1944. “Cookie” Long suffered concussion when a bed board fell the full height of the entrance shaft – 30 feet – and hit him square on the head. Wally Floody received a nasty cut from a hit with a German-issue metal water-carrier, being used to bring sand up from the working to the surface, which struck him a glancing blw to the head. This required bandaging, whcih was explained to the Germans as Floody having slipped on the ice!

The teams had dug out large chambers at the foot of the entrance shafts for the air pump and storage, and took it in turns to operate the manual pump. The ventilation and trolley transport systems were designed by S/Ldr Bob Nelson (crash landed, September 18th 1942 in a Wellington in the Western Desert).

The teams had dug out large chambers at the foot of the entrance shafts for the air pump and storage, and took it in turns to operate the manual pump. The ventilation and trolley transport systems were designed by S/Ldr Bob Nelson (crash landed, September 18th 1942 in a Wellington in the Western Desert).

Left the entrance chamber to ‘Harry’. Note the ventilation trunking made from ‘Klim’- tins of dried milk which the Red Cross supplied to the PoWs

As the tunnel progressed, these dried-milk tins were laid under the floor, and caulked with tape or waxed string, provided very effective ventilation, with the flue being camouflaged into the genuine stove’s chimney.

A wooden railway carried small trucks for sand removal along the bed of the tunnel, the trolleys being pulled from haulage points at intervals along the length.

Red Noble spotted an 800 foot coil of electrical flex unattended by German workmen and ‘liberated’ it; the tunnel was then wired for electric light. The workmen didn’t report the theft and were later executed by the Gestapo when the tunnel was discovered. (Joe “Red” Noble stayed with the RCAF after WW2 and ended up as a Group Captain. He lived on Lake Huron, Canada, and died some years ago.)

Right the tunnel view, with ‘railway’ and ‘trolley’ shown.

Right the tunnel view, with ‘railway’ and ‘trolley’ shown.

The Germans were aware that something major was going on but all attempts to discover tunnels failed. In early March 1944 in a desperate move, 19 top suspects, including Wally Floody, George Harsh, Peter Fanshawe and Bob Stanford-Tuck, were transferred with no warning to the nearby Stalag VIIIC at Belaria. This was only weeks before the escape was scheduled to take place. Bushell’s part in the Escape Committee was well camouflaged and the Germans left him behind. Deputies took over from the missing prisoners, and work went on.

Even when the Luftwaffe removed all the increasing number of American airmen to their own, separate compound, work on the tunnels did not stop. Communication between the separate compounds was forbidden, but the British placed a semaphore expert well inside one hut which faced the US airmens’ compound. He was concealed from the guards, but visible on the other side of the wire. The US airmen soon spotted him, and communications were quickly resumed.

‘Dick’ was abandoned when the area in which it was to have surfaced was suddenly cleared of trees and a new compound built there. However, the abortive short tunnel proved an ideal place for concealing the growing amount of false clothing and general contraband, as well as providing a workshop for the manufacturers.

Later, when sand disposal fell well behind the digging, much of the surplus sand was shovelled down ‘Dick’.

The Canadian pilot F/Lt John Gordon “Scruffy” Weir, shot down in 401 Sqdn Spitfire AB 922 on 8th November 1941, was one of dedicated tunnellers. I am saddened to report that he died in Toronto on September 20th 2009.

Eventually, such sand disposal methods proved insufficient and the X Committee faced major disposal problems. Eventually it dawned on them that there was a huge closed-off area under the seats of the Theatre. Some time before, the Germans had allowed this to be built, using tools and equipment supplied on parole. Such equipment was never used for other purposes, and the parole system was regarded as inviolate.

Eventually, such sand disposal methods proved insufficient and the X Committee faced major disposal problems. Eventually it dawned on them that there was a huge closed-off area under the seats of the Theatre. Some time before, the Germans had allowed this to be built, using tools and equipment supplied on parole. Such equipment was never used for other purposes, and the parole system was regarded as inviolate.

A drawing of the Theatre stage area, from the auditorium perspective.

But did this also include the results of the paroled equipment, i.e. the Theatre itself? The tools had been properly returned, after all … internal “legal advice” was taken, and the SBO’s decision was that the popular and very successful Theatre itself did not fall within the parole system. Seat 13 was therefore hinged and camouflaged, and the vast triangular space beneath used for sand disposal.

After the Great Escape, in autumn 1944 a 4th tunnel, named “George” was excavated from under this seat 13, and ran in a dog-leg from under the Theatre, towards the German ‘Kommandantur’ area. It was used to conceal escape equipment but was not intended as a pure “escape” tunnel, more as an emergency means of evacuating PoWs in the event of the camp being overun by the advancing Russian army. Its location has never been much of a secret – so it’s tosh to say that it has just been discovered; it’s been marked on several diagrams and maps of the Stalag Luft III site and known about for over thirty years. The UK-TV Channel Four documentary “Digging the Great Escape” covers George’s excavation in August 2011 and valiant attempts to find the entrance to Harry and its deep-down workshops. This programme was broadcast on Monday November 28th 2011. It’s a very good documentary and well worth watching, a real eye-opener into the many difficulties the PoWs had to overcome to engineer their many escape plans.

The sand’s pungent but not unpleasant odour was distinctive and was found to be very evident during such disposal operations under the raked seating. Pipe smokers were therefore engaged to sit in close proximity to the hinged seat, and puff away to camouflage the smell of the sand.

The sand’s pungent but not unpleasant odour was distinctive and was found to be very evident during such disposal operations under the raked seating. Pipe smokers were therefore engaged to sit in close proximity to the hinged seat, and puff away to camouflage the smell of the sand.

Having myself dug up some sand from the site I can support this anecdote – the smell is very obvious!

Many excellent shows were put on in the Theatre, which had an enviable standard. Post-war British Theatre and Television “names” such as Talbot Rothwell, Roy Dotrice, George Cole, and Peter Butterworth appear in the Luft III programmes.

Geoffrey Willatt told me that the Theatre Shows were certainly “one of the redeeming features of the camp.” Rupert Davies, of “Maigret” fame, also featured in productions, Art Crighton being the usual orchestra leader. Art died on July 14th 2013.

Theatre interior, during rehearsals. Note the level of workmanship and fine attention to detail in the set, and the audience seating made from Red Cross boxes. James Gerrard says “My Great Uncle (Gordon Kenneth Gilson) was imprisoned in Stalag Luft III and I have a copy of the theatre picture you reproduce that he sent to my grandfather. I believe ‘Uncle Ken’ as we knew him (he died some years ago) is the fifth from the left in the front row. If you have any further information about the image (such as a date or names of the individuals), or know of a source that contains such information I’d be very interested. “

Anyone interested in PoW Camp Theatres and Actors should look at the page devoted to the British actor Michael Goodliffe.

Even a highly simplistic calculation shows that at the barest minimum, for Harry alone the prisoners had to dispose of a staggering ((336 + 28 + 30) x 4) = 1,536 cubic feet of sand. In practice, the actual figure was well over double this, as it does not include the sand excavated for either Tom or Dick or the amount of extra sand removed after roof falls, or the addition of haulage, air pumping and storage chambers. I estimate that for the Great Escape only, the prisoners disposed of a figure in the region of 140 cubic metres, 200 tons of sand, which works out to almost an entire large truck or 40-foot container’s worth. A lot of sand.

‘Harry’ was completed on 14th March, 1944 and the Escape planned around the dark moon, an added bonus being that the dreaded ferret ‘Rubberneck’ was on leave at that time!

A breakdown of the materials used in constructing the three tunnels went as follows, and illustrates the magnitude and logistical problems of the project. This list does not include materials used for false papers and fake civilian clothing, nor the man-hours necessary to actually build the tunnels, or the problems associated with spiriting away the items used in the tunnel construction:-

Ø 4,000 bed boards; 1,370 beading battens; 1,699 blankets; 161 pillow cases; 635 palliasses; 34 chairs; 52 20-man tables; 90 double tier bunks; 1,219 knives; 478 spoons; 30 shovels; 1,000 feet of electric wire; 600 feet of rope; 192 bed covers; 3,424 towels; 1,212 bed bolsters; 10 single tables; 76 benches; 246 water cans; 582 forks; 69 lamps. This list is taken from a German account of what went missing after being issued to the prisoners.

As Tom neared completion in summer 1943, a ferret discovered the entrance and the Germans destroyed it all. At a length of 285 feet, the Germans did not use the usual method of flooding any discovered tunnels, but planted explosives. As these detonated, the hut containing the entrance was severely damaged by blast travelling along the tunnel length. The hut’s concrete floor was destroyed and a significant part of the roof blown off.

Concentration switched to ‘Harry’ which in March 1944 reached the length of 336 feet (some sources say 360 feet, but this may have included the vertical shafts), 28 feet down. Would-be escapers were divided into two groups:-

Firstly, those German-speakers and experienced escapers who stood a good chance of making a “home run” to England, and those who had made the greatest contribution to the construction of the tunnel. These men were given priority with forged papers, “civilian” clothes, and a higher place in the exit order. They were expected to travel by train, masquerading as foreign workers. Germany at the time was flooded with genuine foreign workers, who often spoke no German and whose papers were frequently out of order.

Secondly, the “hard-arsers” who filled the rest of the tunnel places were planning to lie up by day and foot-slog by night, over hundreds of miles of enemy territory. Equipped with only the most rudimentary false papers and identities, much praise is due to this group of men, who knew that their chances – especially in winter – were thin. Most of them had baked iron rations known as “fudge” which was poured into small, pocket-sized tins, and intended as survival food. The rest of the prisoners drew lots, and 220 men prepared to go on the night of March 24/25th, 1944. Snow still lay on the ground and the night time temperature was below freezing.

Whilst the men at the top of the escape list – the experienced escapers, those who spoke good or fluent German, or who had contributed the most effort in the tunnelling operations – had passable ‘civilian’ clothing, the vast majority of other would-be escapers had clothes which were little changed from their original military cut. This large group of men had minimal food and equipment and were not expected to make successful home runs, fuelling Roger Bushell’s plan of flooding the country with a large number of escaped PoWs, to swamp the Germans’ resources.

The Escapers Get Away

As night fell those allocated a place on the tunnel moved to Hut 104. Prisoners, nerves at cracking-point, were terrified to see a German soldier enter the hut. It was F/O Pawel Tobolski, (301 Sqdn, shot down over Bremen, 25/26-Jun-1942, Wellington IV, Z1479 GR:A) dressed for his escape as a German soldier, travelling in company with W/C Day. (I was very pleased to receive emails from and subsequently meet F/O Tobolski’s son, Paul, who had seen this page.) On freeing up the frozen and swollen boards which protected the final upper section of the end vertical shaft at 2215, F/L Johnny Bull discovered that the tunnel mouth was short of the tree line.

The ‘shortage’ distance is variously quoted as 15 or 30 feet. Also it was within 15 yards of the nearest watch tower. But guards were watchful towards the compound and did not shine their searchlights outside. The first escaper went onto the trolley railway at 22:30. With all the forged documents bearing the current date, shutting down the tunnel to excavate another 15 or so feet was not an option.

None of the PoWs I have interviewed have been able to explain why the tunnel came up short, but the most likely explanation is a triangulation and measurement error. It was not easy to accurately measure the length of the tunnel or the angle at which it was being cut. In order to avoid being detected by buried microphones, the tunnel was so deep that the normal method of cautiously poking up a stick to the surface and having this observed and measured on the surface was not possible. Dead reckoning was the only solution, and unfortunately a 5% or 10% error over the 300 foot length proved to be serious. Bearing in mind the formidable difficulties involved with its construction, the PoWs did an astonishing job in completing it at all, without detection. Another likely answer is that a difference in the tunnel’s gradient between halfway houses was enough to skew the measurements and triangulation.

Prowling sentries circled outside the wire, passing at intervals between the tree line and the camp compound. Snow lay on the ground and it was impossible for the escapers not to leave a trail as they hastily crawled out of the exit and into the cover of the trees. This greatly slowed the passage of escapers, a situation worsened by an air raid which made the Germans switch off the power, forcing the use of fat lamps inside the tunnel.

Marshall and Bull were the first out with a length of rope for tugging and signalling and the exit of men was seriously slowed down by this method, and the need for experienced tunnellers to clear an unpected roof fall. It was soon apparent in Hut 104 that things were going badly wrong, but little news filtered back from the far end of the tunnel. A request for a long length of rope was fulfilled, but the passage of men stalled. Gordie King kept pumping away to keep air going down the tunnel shaft. Although the briefing had called for each man to ride the tiny railway trolley, being pulled by the previous man, once the tunnel had swallowed the first couple of dozen, no more were being called. The dispatcher, waiting at the tunnel entrance, had no more idea what was wrong than did the long queue of impatient and highly-strung men.

The necessity to wait until the circuiting sentries were not close to the tunnel exit, and the need to exercise great discretion in sending the next man out, considerably slowed the throughput. Instead of one man every minute, the escape was reduced to a dozen per hour. Word was sent back that those men with escape numbers higher than 100 had no chance of escaping. Since exiting Hut 104 during the curfew to return to their own huts would entail being shot at by the guards, they lay down where they could to await daylight. By dawn, only 76 men had made their escape into the darkness beyond the trees.

At 04:55, by which time 87 escapers had left Hut 104, F/L Shand at the mouth of the tunnel was awaiting the signal to go. In the woods was F/L Langlois (12 Sqdn, shot down 5-Aug-1941, Wellington II, W5421 PH:G) who could see that a patrolling sentry had deviated from his beat and would tread within a few feet of the tunnel. He tugged at the signal rope, meaning “stay put.” Shand, thinking this was the opposite signal, emerged from the tunnel right under the feet of the guard, who until then had passed by.

For some seconds he did not see the tracks in the snow and body-heat steam drifting upwards from the tunnel mouth. Finally noticing the signs, he raised his rifle, fired a wild shot at Langlois (which missed) and blew his whistle. F/L Laurence Reavell-Carter (49 Sqdn, shot down 26/27-Jun-1940, Hampden I P4305) and F/L Keith “Skeets” Ogilvie, waiting in the woods, ran for it and so did Shand. The next man in the tunnel, S/L Robert Frederick McBride (415 Coastal Sqdn RCAF, shot down early November 1942) , was apprehended at rifle point, and S/L Len Trent (487 Sqdn, shot down 3-May-1943, Ventura II AJ209, EG:V) a holder of the VC and DSO, lying face down just inside the tree line, stood up and surrendered.

F/O Ken “Shag” Rees (150 Sqdn, shot down 23/24-Oct-1942, Wellington III BK309, JN:N) and S/L Clive Saxelby (103 Sqdn, shot down 7/8 Sep-1942, Halifax W1219 PM:S) were in the tunnel close to the foot of the final ladder, awaiting their turns to exit. On hearing the shots, Sax together with Joe Moul (416 Sqdn, shot down 23 Oct 42, Spitfire Vb BL575), hared at top speed on all fours back the way they had come, closely followed by Rees, who believing a ferret might jump down the escape end and shoot along the tunnel, tried to kick out the shoring, with little success. Ken said “As I was haring up the tunnel, all I could see was Sax’s bum blocking the way and I expected a bayonet or a bullet up my arse at any moment!” S/L Denys Maw (218 Sqdn, shot down Gelsenkirchen, 25/26 Jun 43, Strirling EF430 HA:W) also made it back to Hut 104. Ken Rees was the last man up.

(I am sorry to report that Clive Saxelby died on March 22nd 1999. When I interviewed him at his home in Torquay in August 1997, he was quite genuinely astounded that anyone was interested in his time with 103 Sqdn or his contribution to the Great Escape. His comment at the end of the evening was “I’m sorry I can’t remember very much but I haven’t thought about, or considered important, any of this, for forty years.”

I am equally sorry to report that Ken Rees died on August 30th 2014, having been unwell for some time. I only met him the once at his home in Anglesey, but he was very entertaiing to listen to and gave me much information on 150 Sqdn and his time at Luft III.)

After a few minutes, all the men who had been waiting in the tunnel managed to return to Hut 104, where the shots had also been heard. The escapers remaining, and those scrambling out of the tunnel entrance, burned their false papers and began to eat their carefully-saved rations, as the Germans would be sure to confiscate them. However, the guards had no idea where the tunnel started and had searched Hut 104 so many times that they considered it safe; they therefore searched every hut and it was some time before they reached 104, by which time rations had been mostly eaten, false papers mostly burned and some escapers had even managed to return to their correct huts.

The ferrets in 104 could not find the entrance; their dog crawled into a pile of coats and fell asleep. Finally, the ferret Charlie Pilz crawled down from the tunnel’s far end. By this time the Germans were in Hut 104 and noises could be heard from underneath as Charlie shouted for help. Taking pity on him, the prisoners opened the trap and Charlie emerged, full of praise for the superb tunnel.

In the darkness, many of the escapers had not found the railway station entrance, which was unusually positioned in a dark recessed pedestrian tunnel, right under the actual platforms. Consequently, many of them missed their trains and were very unhappily hanging round the platforms at first light, trying to ignore each other. Eventually they caught the first trains out of Sagan, or having given up the wait, footslogged it over the horizon. Due to this sad delay, they were nearly all caught in the Sagan area.

The Reprisal

The balloon went up in spectacular style. A ‘Grossfahndung’ (national alert) was ordered with troops, police, Gestapo and Landwacht (Home Guard) alerted. Hitler, incensed, ordered that all those recaptured were to be shot. Goering, Feldmarschall Keitel, Maj-Gen Graevenitz and Maj-Gen Westhoff tried to persuade Hitler to see sense. Eventually he calmed down and decreed that ‘more than half are to be shot and cremated.’ This directive was teleprinted to Gestapo headquarters under Himmler’s order, and a list of 50 was composed by General Nebeand Dr Hans Merton.

One by one the escapers were recaptured and on Himmler’s orders, handed over to the Gestapo. This was not the normal practice; usually, recaptured PoWs were handed over to, and dealt with, by the civilian police. Singly, or in small groups, they were taken from civilian or military prisons, driven to remote locations, and shot whilst offered the chance to relieve themselves. The Gestapo groups submitted almost identical reports that ‘the prisoners whilst relieving themselves, bolted for freedom and were shot whilst trying to escape.’‘

Three escapers, Per Bergsland (aka Rocky Rockland, because he Anglicised his name as the authorities were unsure how Norwegians serving in the RAF and then becoming PoWs would be treated by the Germans),  (332 Sqdn, shot down Spitfire VB AB269 AH:D, during the Dieppe Landings), Jens Muller (331 Sqdn, shot down 19th June 1942, Spitfire VB AR298 FN:N), and Bram (“Bob”) van der Stok (left, 41 Sqdn, shot down July 1942, Spitfire Vb BL595), succeeded in reaching safety. Bergsland and Muller reached neutral Sweden, and van der Stock arrived in Gibraltar via Holland, Belgium, France and Spain. Out of the 73 others, 50 were murdered by the Gestapo, 17 were returned to Sagan, four sent to Sachsenhausen, and two to Colditz Castle. Word reached England of the atrocity; in mid July 1944 Anthony Eden, British Foreign Minister, made a speech in the House of Commons declaring that the perpetrators of the crime would be brought to justice.

(332 Sqdn, shot down Spitfire VB AB269 AH:D, during the Dieppe Landings), Jens Muller (331 Sqdn, shot down 19th June 1942, Spitfire VB AR298 FN:N), and Bram (“Bob”) van der Stok (left, 41 Sqdn, shot down July 1942, Spitfire Vb BL595), succeeded in reaching safety. Bergsland and Muller reached neutral Sweden, and van der Stock arrived in Gibraltar via Holland, Belgium, France and Spain. Out of the 73 others, 50 were murdered by the Gestapo, 17 were returned to Sagan, four sent to Sachsenhausen, and two to Colditz Castle. Word reached England of the atrocity; in mid July 1944 Anthony Eden, British Foreign Minister, made a speech in the House of Commons declaring that the perpetrators of the crime would be brought to justice.

At the camp, von Lindeiner-Wildau, the Kommandant, had surrendered to his superiors and been arrested. He escaped execution, and was sentenced to fortress arrest, which he survived, partly by feigning mental illness to secure an early release. A new man, Oberst (Colonel) Erich Cordes, arrived. On April 6th 1944 he called G/C Massey to his office. Under different circumstances, von Lindeiner and Massey, both professional and honourable career Air Force officers, would have been friends. Normally such meetings were as cordial as the peculiar circumstances allowed, and were preceded with a formal handshake. This time and with a new man in command, there was none. With a clear reluctance, the new Kommandant announced via the interpreter, S/L Philip ‘Wank’ Murray, (102 Sqdn, shot down 8/9-Sep-39, Whitley III K8950 DY:M) that he was ordered to inform the Senior British Officer that forty-one escaping officers had been “shot whilst trying to escape.” Massey couldn’t believe it. “How many were wounded?” he asked, staggered. “None, and I am not permitted to give you any further information, except that their bodies and personal effects will be returned to you,” was the stilted reply.

(Another source, Airmen’s Obituaries published by the Daily Telegraph, quotes Aidan Crawley as the interpreter at that time, and that the dreadful news was given to “G/C Wallis, the SBO”.)

“Shot whilst trying to escape” thereafter became an evil euphemism for cold blooded murder.

Prisoners and Luftwaffe alike were horrified. Hauptmann Pieber, the adjutant, afterwards said to Murray, “You must not think the Luftwaffe had anything to do with this … we do not wish to be associated … it is terrible.” Later the list of names was posted and contained 47 names; an update a few days later added three more. The aftermath was a grim time with the Gestapo investigators poking their noses everywhere and prisoners and guards alike were very edgy. Pieber even told the PoWs to “be very careful, you are in great danger; no more tricks.”

Pieber, too, was respected by the PoWs, and habitually congratulated prisoners who were promoted whilst in captivity, usually shaking their hand. Promotions which had been put into motion before a man was shot down would duly be notified to the Red Cross by the Air Ministry, and then word filtered down through the German High Command.

Peter Hynes reports that “the morning after the prisoners learned about the officers getting shot, every prisoner appeared with a black diamond sewn on their sleeves, some using their last pair of socks.”

Simoleit was a professor of History, Geography and Ethnology, spoke several languages including English, Russian, Polish and Czech. Transferred to Sagan in early 1943, he was deputy Kommandant and ignored the ban on military courtesies to PoWs by providing full honours at the funeral of an RAF airman who was also Jewish.

Von Lindeiner died in 1963, aged 82; in his memoirs he expressed appreciation for the genuine sympathies of G/C Massey and the other Commonwealth officers when his Berlin apartment was destroyed by Allied bombers.

Later the Luftwaffe quietly allowed the prisoners to build a local memorial (view this on the ‘Modern Photos‘ page). This was designed by Wylton Todd (169 Sqdn, shot down 15/16-Feb-44, Mosquito II, HJ707 VI:B), and two of the stonemasons who carved the names were Dickie Head (possibly 139 Sqdn, shot down 24/25-Nov-43, Mosquito IV DZ614) and S/L John Hartnell-Beavis (10 Sqdn, shot down 25/26-Jul-1943, Halifax II, JD207 ZA:V, a former architect) and erected in the local cemetery. John died in July 2004 but I am in touch with Wylton Todd’s grandson, Peter Hynes.

Urns containing ashes of the Fifty were originally buried there, but after the war were taken to the Old Garrison Cemetery at Poznan.

Both still remain today. If you visit the camp you will find many traces of the wartime era. Take time to walk into the woods well beyond Hut 104 and explore the more distant parts. There is a local museum, of exhibits and items found at the camp. Paul Tobolski on visiting the memorial, corrected a small error on his father’s initials, and liberated one of the tiles from Harry’s entrance. He had never known his father.

If you go on one of these organised ‘Battlefield’ tours, the guide will probably know less about it than you, so print off this page, as well as the Modern Photos one, and take them with you. Insist on at least an hour on the site, and the same at the Museum.

|

The Fifty Victims |

|||

|

J/35233 F/L Henry J Birkland, Canadian, born 16-Aug-1917, 72 Sqdn, (shot down 7-Nov-1941, Spitfire Vb, W3367), recaptured near Sagan, last seen alive 31-Mar-1944; murdered by Lux and Scharpwinkel; cremated at Liegnitz. |

(IWM) |

(IWM) |

61053 F/L E Gordon Brettell DFC, British, born 19-Mar-1915, 133 (Eagle) Sqdn (shot down 26-Sep-1942, Spitfire IX BS313), recaptured Scheidemuhl, murdered by Bruchardt 29-Mar-1944, cremated at Danzig. |

|

43932 F/L Leslie George Bull DFC, British, born 7-Nov-1916, 109 Sqdn (shot down 5/6-Nov-1941, Wellington IC, T2565) recaptured near Reichenberg, murdered 29-Mar-1944 by unknown Gestapo, cremated at Brux.. (See the entry for Mondschein) |

(IWM) |

(IWM) |

90120 S/L Roger J Bushell, South African born but in the regular RAF, born 30-Aug-1910, 92 Sqdn (shot down 23-May-1940, Spitfire I, N3194) recaptured at Saarbrucken, murdered 29-Mar-1944 by Schulz, cremated at Saarbrucken. |

|

39024 F/L Michael J Casey, British, born 19-Feb-1918, 57 Sqdn (shot down 16-Oct-1939, Blenheim I, L1141), recaptured near Gorlitz, murdered 31-Mar-1944 by Lux and Scharpwinkel, cremated at Gorlitz. |

(IWM) |

(IWM) |

Aus/400364 S/L James Catanach DFC, Australian, born 28-Nov-1921, 455 (RAAF) Sqdn (crash landed in Norway, 6-Sep-1942, Hampden I AT109), recaptured at Flensburg, murdered 29-Mar-1944 by Post, cremated at Kiel. Parents from Malvern, Victoria, Australia. |

|

NZ/413380 F/L Arnold G Christensen, New Zealander, 26 Sqdn, born 8-Apr-1922, taken PoW 20-Aug-1942 after engine failure in Mustang AL977, recaptured at Flensburg, murdered 29-Mar-1944 by Post, cremated at Kiel. |

(IWM) |

(IWM) |

122441 F/O Dennis H Cochran, British, born 13-Aug-1921, 10 OTU, shoty down and taken PoW 9-Nov-1942 (Whitley V, AD671) , recaptured at Lorrach, murdered 31-Mar-1944 by Priess and Herberg, cremated at Natzweiler. |

|

39305 S/L Ian K P Cross DFC, British, born 4-Apr-1918, 103 Sqdn (shot down 12-Feb-1942, Wellington IC, Z8714 PM:N), recaptured near Gorlitz, murdered 31-Mar-1944 by Lux and Scharpwinkel, cremated at Gorlitz. |

(IWM) |

(IWM) |

110378 Lt Halldor Espelid, Norwegian, born 6-Oct-1920, 331 Sqdn. Shot down by flak 27 Aug 42, Spitfire Vb BL588 FN:A east of Dunkirk, recaptured at Flensburg, murdered 29-Mar-1944 by Post, cremated at Kiel. |

|

42745 F/L Brian H Evans, British, born 14-Feb-1920, 49 Sqdn (shot down 6-Dec-1940, Hampden I, P4404 EA:R), recaptured at Halbau; last seen alive 31-Mar-1944, murdered by Lux and Scharpwinkel; cremated at Liegnitz. |

(IWM) |

(IWM) |

742 2/Lt Nils Fuglesang, Norwegian, 332 Sqdn. Shot down and belly landed in Holland (Spitfire IX BS540 AH:E) 2-May-1943, recaptured at Flensburg, murdered 29-Mar-1944 by Post, cremated at Kiel. Photo of crashed aircraft, p.94 Volume 2, FIGHTER COMMAND LOSSES |

|

103275 Lt Johannes S Gouws, South African, born 13-Aug-19, 40 Sqdn SAAF,shot down in Tomahawk AN377 and PoW 9-Apr-1942, recaptured at Lindau, murdered 29-Mar-1944 by Schneider, cremated at Munich. |

(IWM) |

(IWM) |

45148 F/L William J Grisman, British, born 30-Aug-14, 109 Sqdn, (believed shot down 5/6-Nov-1941, Wellington IC, T2565) recaptured near Gorlitz, last seen alive 6-Apr-1944; murdered by Lux, cremated at Breslau. |

|

60340 F/L Alastair D M Gunn, British, born 27-Sep-1919, 1 PRU, shot down in Spitfire PR.IVAA810 and PoW 5-Mar-1942, recaptured near Gorlitz, last seen alive 6-APR-1944, murdered by unknown Gestapo, cremated at Breslau. |

(IWM) |

(IWM) |

Aus/403218 F/L Albert H Hake, Australian, born 30-Jun-1916, 72 Sqdn, shot down 4-Apr-42, Spitfire Vb AB258, recaptured near Gorlitz, murdered 31-Mar-1944 by Lux and Scharpwinkel, cremated at Gorlitz. Wife from Carlton, Sydney, Australia. |

|

50896 F/L Charles P Hall, British, born 25-Jul-1918, 1 PRU, shot down in Spitfire AA804 and PoW 28-Dec-1941, recaptured near Sagan, murdered 30-Mar-1944 by Lux and Scharpwinkel, cremated at Liegnitz. |

(IWM) |

(IWM) |

42124 F/L Anthony R H Hayter, British, born 20-May-1920, 148 Sqdn, shot down in Wellington BB483 and PoW 24-Apr-1942, recaptured near Mulhouse, murdered 6-Apr-1944 by Schimmel, cremated at Natzweiler. |

|

44177 F/L Edgar S Humphreys, British, born 5-Dec-1914, 107 Sqdn (shot down 19-Dec-1940, Blenheim IV, T1860), recaptured near Sagan, last seen alive 31-Mar-1944, murdered by Lux and Scharpwinkel, cremated at Liegnitz. |

(IWM) |

(IWM) |

J/10177 F/L Gordon A Kidder, Canadian, born 9-Dec-1914, 156 Sqdn (shot down 13/14-Oct-1942, Wellington III, BJ775) recaptured near Zlin, murdered 29-Mar-1944 by Zacharias and Knippelberg, with drivers Kiowsky and Schwartzer, cremated at Mahrisch Ostrau. |

|

Aus/402364 F/L Reginald V Kierath, Australian, born 20-Feb-1915, 450 Sqdn, shot down Kittyhawk III FR477 and PoW 23-Apr-1943, recaptured near Reichenberg, murdered 29-Mar-1944 by unknown Gestapo, cremated at Brux.. (See the entry for Mondschein) |

(IWM) |

(IWM) |

P/0109 Maj Antoni Kiewnarski, Polish, born 26-Jan-1899, 305 Sqdn (shot down 28-Aug-1942, Wellington X, Z1245), recaptured at Hirschberg, murdered there 31-Mar-1944 by Lux, place of cremation unknown. (See the entry forMondschein) |

|

39103 S/L Thomas G Kirby-Green, British, born 28-Feb-1918, 40 Sqdn (shot down 16/17-Oct-1941, Wellington IC, Z8862 BL:B), recaptured near Zlin, murdered 29-Mar-1944 by Zacharias and Knippelberg, with drivers Kiowsky and Schwartzer, cremated at Mahrisch Ostrau. Described to me as “a tall, suave aristocrat.” |

(IWM) |

(IWM) |

P/0243 F/O Wlodzimierz Kolanowski, Polish, born 11-Aug-1913, 301 Sqdn (shot down 8-Nov-1942, Wellington IV, Z1277 GR:Z), recaptured near Sagan, shot at Liegnitz 31-Mar-1944 by Lux and Scharpwinkel, cremated at Liegnitz. |

|

P/0237 F/O Stanislaw Z Krol, Polish, born 22-Mar-1916, 74 Sqdn (shot down 2-Jul-1941, Spitfire Vb, W3263), recaptured at Oels, shot at Breslau 14-Apr-1944 probably by Lux, cremated at Breslau. |

(IWM) |

(IWM) |

J/1631 Patrick W Langford, Canadian, born 4-Nov-1919, 16 OTU, (shot down 28/29-Jul-1942, Wellington IC, R1450) recaptured near Gorlitz, last seen alive 31-Mar-1944, murdered by Lux and Scharpwinkel; cremated at Liegnitz. |

|

46462 F/L Thomas B Leigh, Australian in RAF, born 11-Feb-1919, 76 Sqdn (shot down 5/6-Aug-1941, Halifax I, L9516), recaptured in Sagan area; last seen alive 12-Apr-1944, murdered by Lux and Scharpwinkel; cremated at Breslau. |

(IWM) |

(IWM) |

89375 F/L James L R Long, British, born 21-Feb-1915, 9 Sqdn (shot down 27-Mar-1941, Wellington IA, R1335 WS:K), recaptured near Sagan, last seen alive 12-Apr-1944, murdered by Lux; cremated at Breslau. |

|

95691 2/Lt Clement A N McGarr, South African, born 24-Nov-1917, 2 Sqdn SAAF, shot down Tomahawk AK513 and PoW 6-Oct-1941, recaptured near Sagan, last seen alive 6-Apr-1944, murdered by Lux, cremated at Breslau. |

(IWM) |

(IWM) |

J/5312 F/L George E McGill, Canadian, born 14-Apr-1918, 103 Sqdn. With 3 others, baled out of a damaged Wellington R1192 10/11-Jan-1942 over Germany, on an operation to Wilhelmshaven. The Wellington managed to limp back to Elsham Wolds. Recaptured in Sagan area, last seen alive 31-Mar-1944, murdered by Lux and Scharpwinkel; cremated at Liegnitz. |

|

89580 F/L Romas Marcinkus, Lithuanian, born 22-Jul-10, 1 Sqdn, shot down 12-Feb-42, Hurricane IIc BD949 “JX:J”, recaptured at Scheidemuhl, murdered 29-Mar-1944 by Bruchardt, cremated at Danzig. |

(IWM) |

(IWM) |

103586 F/L Harold J Milford, British, born 16-Aug-14, 226 Sqdn, believed shot down Boston AL743 and PoW 22-Sep-1942, recaptured near Sagan, last seen alive 6-Apr-1944, murdered by Lux; cremated at Breslau. |

|

P/0913 F/O Jerzy Tomasc Mondschein, Polish, born 18-Mar-09, 304 Sqdn (shot down 8-Nov-1941, Wellington IC, R1215), recaptured in Reichenberg area, murdered Brux 29-Mar-1944 by unknown Gestapo, cremated at Brux. A Polish correspondent says “The killers are unknown but these executions were orchestrated by local Reichenburg Gestapo leader Bernhard Baatz, Robert Weissman and Robert Weyland. Baatz and Weyland lived on with impunity and with the complicity of the Russian authorities. Weissman was later arrested by the French military authorities but his fate remains unknown.” |

(IWM) |

(IWM) |

P/0740 F/O Kazimierz Pawluk, Polish, born 1-Jul-06, 305 Sqdn (shot down 29-Mar-1942, Wellington II, W5567 SM:M), recaptured at Hirschberg, shot there on 31-Mar-1944 by Lux, place of cremation unknown. |

|

87693 F/L Henri A Picard Croix de Guerre,Belgian, born 17-Apr-1916, 350 Sqdn, shot down Spitfire BM297 and PoW 2-Sep-1942, recaptured at Scheidemuhl, murdered 29-Mar-1944 by Bruchardt, cremated at Danzig. |

(IWM) |

(IWM) |

NZ/402894 F/O John P P Pohe, New Zealander, born 10-Dec-1921, 51 Sqdn (shot down 22/23-Sep-1941, Halifax II, JN901) recaptured near Gorlitz, murdered 31-Mar-1944 by Lux and Scharpwinkel, cremated at Gorlitz. Also known by his Maori name of Porokoru Patapu. |

|

30649 Sous-Lt Bernard W M Scheidhauer,French, born 28-Aug-21, 131 Sqdn, ran low on fuel and landed by mistake on Jersey, 18 Nov 1942, Spitfire Vb EN830 NX:X, recaptured at Saarbrucken, murdered 29-Mar-1944 by Spann, cremated at Saarbrucken. |

|

(IWM) |

213 P/O Sotiris Skanzikas, Greek, born 6-Aug1921, 336 Sqdn, shot down Hurricane HW250 and PoW 23-Jul-1943, recaptured at Hirschberg, murdered 30-Mar-1944 by Lux, place of cremation unknown. |

|

47341 Rupert J Stevens, South African, born 21-Feb-1919, 12 Sqdn SAAF, Shot down in Martin Maryland AH287 and PoW 14-Nov-1941, recaptured at Rosenheim, murdered 29-Mar-1944 by Schneider; cremated at Munich. |

(IWM) |

(IWM) |

130452 F/O Robert C Stewart, British, born 7-Jul-1911, 77 Sqdn (shot down 26/27-Apr-1943, Halifax II, DT796) recaptured near Sagan, last seen alive 31-Mar-1944, murdered by Lux and Scharpwinkel; cremated at Liegnitz. |

|

107520 F/L John G Stower, British, born 15-Sep-1916, 142 Sqdn (shot down 16/17-Nov-1942, Wellington III, BK278, QT:C), recaptured near Reichenberg, murdered 31-Mar-1944 by unknown Gestapo; place of cremation unknown. |

(IWM) |

(IWM) |

123026 F/L Denys O Street, British, born 1-Apr-1922, 207 Sqdn (shot down 29/30-Mar-1943, Lancaster I, EM:O), recaptured near Sagan, last seen alive 6-Apr-1944, murdered by Lux; cremated at Breslau. Street is the only victim whose ashes are not at Poznan; his rest at the Berlin 1939-1945 War Cemetery. |

|

37658 F/L Cyril D Swain, British, born 15-Dec-1911, 105 Sqdn (shot down 28-Nov-1940, Blenheim IV, T1893), recaptured near Gorlitz, last seen alive 31-Mar-1944, murdered by Lux and Scharpwinkel; cremated at Liegnitz. |

(IWM) |

(IWM) |

P/0375 F/O Pawel Whilem Tobolski, Polish, born 21-Mar-1906, 301 Sqdn (shot down 25/26-Jun-1942, Wellington IV Z1479, GR:A), recaptured at Stettin, shot at Breslau 2-Apr-1944 probably by Lux, cremated at Breslau. |

|

82532 F/L Arnost Valenta, Czech, born 25-Oct-1912, 311 Sqdn (shot down 6-Feb-1941, Wellington IC, L7842 KX:T), recaptured near Gorlitz, last seen alive 31-Mar-1944, murdered by Lux and Scharpwinkel; cremated at Liegnitz. |

(IWM) |

(IWM) |

73022 F/L Gilbert W Walenn, British, born 24-Feb-1916, 25 OTU, shot down Wellington N2805 and PoW 11-Sep-1941, recaptured at Scheidemuhl, murdered 29-Mar-1944 by Bruchardt, cremated at Danzig. |

|

J/6144 F/L James C Wernham, Canadian, born 15-Oct-1917, 405 Sqdn (shot down 8/9-Jun-1942, Halifax II, W7708 LQ:H), recaptured at Hirschberg, murdered 31-Mar-1944 by Lux, place of cremation unknown. |

(IWM) |

(IWM) |

J/7234 F/L George W Wiley, Canadian, born 24-Jan-1922, 112 Sqdn, shot down Kittyhawk III 245788 and PoW 12-Mar-1943, recaptured near Gorlitz, murdered 31-Mar-1944 by Lux and Scharpwinkel, cremated at Gorlitz. |

|

40652 S/L John Edwin Ashley Williams DFC, Australian in RAF, born 6-May-1919, 450 Sqdn, shot down Kittyhawk III FR270 and PoW 31-Oct-1942, recaptured near Reichenberg, murdered 29-Mar-1944 by Lux, cremated at Brux. |

(IWM) |

(IWM) |

106173 F/L John F Williams, British, born 7-Jul-1917, 107 Sqdn (shot down 27-Apr-1942, Boston III Z2194), recaptured near Sagan, last seen alive 6-Apr-1944, murdered by unknown Gestapo; cremated at Breslau. |

Here is a private tribute to the 50; and here is a link to some archived photographs of four of the escapers.

Ian Le Sueur reports that a memorial to Bernard Scheidhauer was unveiled by his sister on September 17th 1999, the service was attended by over 300 people including members of his family, Free French Air Force veterans, and also Great Escape’s  Sydney Dowse (left) and Raymond Van Wymeersch (174 Free French Sqdn, shot down Hurricane IIc BP299 XP:U). The service ended with a fly past by a Spitfire MkVb and two Mirage 2000 of the French Air Force.

Sydney Dowse (left) and Raymond Van Wymeersch (174 Free French Sqdn, shot down Hurricane IIc BP299 XP:U). The service ended with a fly past by a Spitfire MkVb and two Mirage 2000 of the French Air Force.

The Survivors

Evaded recapture and returned to England:-

F/Lt Per (or Peter) Bergsland (Norwegian, 332 Sqdn, shot down 19 Aug 42, Spitfire Vb AB269, aka “Rocky Rockland”) born 17-Jan-19, died 9-Jun-92. There is a fine study of this officer on page 61 of Norman Franks’ book FIGHTER COMMAND LOSSES : Volume 2 (ISBN 1857800753).

Jens Muller (Norwegian) 331 Sqdn

… both reached England via Sweden, in March. Muller’s son Jon Muller advises me that he died on March 30th, 1999.

F/Lt Bob van der Stok (or Vanderstok) (Dutch, 41 Sqdn, shot down 12 Apr 42, Spitfire Vb BL595) born 13-Oct-15, became a paediatrician, and having lived in Santa Barbara and Hawaii, died in 1993

– reached England via Spain, in July

Recaptured and returned to Luft III, Sagan:-

F/Lt Albert Armstrong 109946 (268 Sqdn, died 1987)

F/Lt R Anthony Bethell 120413 (268 Sqdn, shot down near Alkmaar, 7-Dec-1942, Mustang AP212 ‘V’) born 9-Apr-22. Died February 2004.

F/Lt Leslie Charles James Brodrick 122363 (106 Sqdn, shot down Stuttgart, 14/15-Apr-1943, Lancaster ED752 ZN:H, born May 1921, died April 2013, in South Africa).

F/O William J Cameron J6487 (RCAF, since died).

F/Lt Richard Sidney Albion Churchill 41255 (144 Sqdn, born 1918).

F/Lt Bernard “Pop” Green 76904 (44 Sqdn, shot down 19/20-Jul-40, Hampden I L4087, died 2nd November 1971).

F/Lt Roy Brouard Langlois (12 Sqdn, shot down 5-Aug-1941, Wellington II, W5421 PH:G). Langlois, (nicknamed Daddy Long Legs) was returned to Sagan. He earned a Distinguished Flying Cross and attained the rank of Wing Commander before retiring from the RAF in 1962. He died in 1993 aged 76.

F/Lt Henry Cuthbert “Johnny” Marshall 36103 gave evidence (by then, a Wing Commander) at the trial of the accused murderers. His eldest daughter, Monica Grey, advises me that he died on July 8th, 1980.

F/Lt Robert McBride lived in Point Claire (Montreal), Quebec, Canada, and died in the 1980s.

F/Lt Alistair Thompson McDonald 115320 (since died)

Lt Alexander Desmond Neely (825 Sqdn Fleet Air Arm, shot down near Dunkirk in May 1940, born November 1917, died October, died in Tiverton at the age of 83. He was the 28th escapee to crawl through the 25ft deep, 300ft long tunnel to freedom. He was only captured because his tie was recognised at a checkpoint. He was an extremely reserved man who seldom talked about his war-time experiences, but he did return to Poland with fellow former POWs in 1994. Scathing about The Great Escape film, he was very annoyed with Steve McQueen and the motorcycle incident, which he said was a load of rubbish because it never happened, he also didn’t like they way Hollywood glamourised it and put in characters who weren’t really there. (Thanks to Richard Miller for permission to quote from his obituary.)

F/Lt Thomas Robert Nelson 70811 (37 Sqdn, born March 1915, died August 25th 1999). Nelson, who had operated previously in North Africa, had the incredible distinction of having crashed in the desert and walked out alive after ten days, having received help from only one passing Arab, who gave him water. He was captured by a German patrol when within only a mile of friendly forces. He later gained an international reputation as an air accident investigator, representing the Government at all five Comet crash inquiries of the 1950s.

F/Lt Alfred Keith Ogilvie DFC 42872 (Canadian, 609 Sqdn, born March 1915, died in Ottawa, Canada, 28 May 1998)

Lt Douglas Arthur Poynter (Fleet Air Arm, born 1921). Mark Horan adds : “Poynter, an Acting/Sub-Lieutenant (A), RN [seniority date 23.04.40] was a observer in 825 Squadron, FAA. On 20 September, 1940, both his squadron and 816 Squadron (Swordfish TSRs), part of 801 Squadron (Skua FDBs), and a section of 804 (Sea Gladiator fighters) were embarked on HMS Furious in order to participate in Operation “DT”, an attack on shipping off Trondheim, Norway.on 22 September. Poynter was a member of the three-man aircrew of Swordfsih L9756, along with Temporary/Lieutenant(A) Henry Deterling, RNVR (Pilot) and Naval Airmen H. W. Brown, RN Fx.77522 (Telegraphist-Air-Gunner).. In the event, their aircraft force-landed Northeast of Trondheim, one of five Swordfish TSRs and one Skua FDB lost in the attack, with a total of three aircrew killed, nine prisoners, and four interned.”

F/Lt Laurence Reavell-Carter (49 Sqdn, died 1985)

F/Lt Paul Gordon Royle 42152 (53 Sqdn RAAF). Alive in Perth, Western Australia (as at January 2012). See this web page.

F/Lt Michael Moray Shand NZ/391368 (485 Sqdn RNZAF) born 18-March-15, died on 20 December 2007 in Masterton, his hometown – north of

Wellington, New Zealand.

F/L Alfred Burke Thompson 39585 (102 Sqdn, shot down 8/9-Sep-39, Whitley III, K8950, died 1985)

S/Ldr Leonard Henry Trent VC (487 Sqdn, shot down 3-May-1943, Ventura II AJ209, EG:G, died 1986)

Recaptured and taken to Sachsenhausen, later returned to Luft III, Sagan:-

F/Lt Ray van Wymeersch 30268 (174 Sqdn Free French Air Force, born September 1920, shot down 19 Aug 42, Hurricane IIc BP299 “U”), died in June 2000.

Recaptured and sent to Stalag Luft I, Barth:

F/Lt Desmond Lancelot Plunkett 78847 (Rhodesian, 218 Sqdn, shot down Emden 20/21-Jun-1942, Stirling I W7530, HA:Q, born February 1915; died February 2002)

Recaptured at sent to Oflag IVC, Colditz Castle:-

F/Lt Bedrich Dvorak 82542 (312 Sqn, shot down by FW 190 of JG 2 on 3/6/42 near Cherbourg in Spitfire VB, BL340, DU-X, born 1912, died 29th August 1973.

F/Lt Ivor B Tonder 83232 (Czech, 312 Sqdn, born April 1913, shot down on 3/6/42 by FW 190 of JG 2 over Channel close by Cherbourg in Spitfire VB, BL626, DU-I) died 4th May 1995.

Recaptured, sent to Sachsenhausen and later escaped to safety:-

W/C Harry Melville Arbuthnot “Wings” Day AM (converted to GC in 1971) DSO OBE 5175 (died 1977)

Maj Johnnie Dodge DSO DSC MC (1896 – 1960). Dodge, related to Winston Churchill, was released into Switzerland by the Germans in an unsuccessful attempt to sue for peace.

F/Lt Sydney Henstings Dowse MC 86685 (PRU, born November 21st, 1918; died April 10th 2008). Another ‘Escaper’, supported by correspondence from readers of this page, described him as “the bastard who ran off with Wings Day’s wife after the war”. His obituary made it clear that he was a wealthy playboy, fond of the high society lifestyle, and had been married three or four times – although single at the time of his death.

F/Lt Bertram Arthur James MC 42232 (left, 9 Sqdn, shot sdown Duisburg 5/6-Jun-1940, Wellington IA P9232 WS:M, born April 1915. His book on the Great Escape was published in Feb 2002. Jimmy James died aged 92 on Friday January 18th, 2008.

F/Lt Bertram Arthur James MC 42232 (left, 9 Sqdn, shot sdown Duisburg 5/6-Jun-1940, Wellington IA P9232 WS:M, born April 1915. His book on the Great Escape was published in Feb 2002. Jimmy James died aged 92 on Friday January 18th, 2008.

(IWM)

|

The Investigators |

||

Bowes (IWM)

Lyon (IWM) |

W/Cdr Wilfred “Freddie” Bowes (top left), F/Lt (later S/Ldr) Francis Peter McKenna (top right), F/Lt (later S/Ldr) “Dickie” Lyon (bottom left), F/Lt Stephen Courtney, F/Lt Harold Harrison(bottom right) and W/O H J Williams, of the Royal Air Force Special Investigation Branch, painstakingly travelled Europe and gradually pieced together enough evidence to identify the culprits. Lt. Col. A P Scotland, an Army Intelligence expert, interrogated many suspects at the London Cage. S/Ldr McKenna died on February 14th, 1994.The Court President at the resulting trials was Maj-General H L Longden; the Judge Advocate was Mr C L Stirling, with a panel of six senior military officers – three Army Colonels, two RAF Wing Commanders and an RAF Air Commodore. Ten German lawyers – one a woman, Dr Anna Oehlert – formed the defence team. The Court pronounced its verdict on September 3rd 1947, and in early February 1948, thirteen of the perpetrators were hanged at Hamelin Gaol, Hamburg. The executioner was the famous Albert Pierrepoint.A short while after this, a second trial took place for three more of the accused. |

McKenna (IWM)

Harrison (IWM) |

W/Cdr Bowes and S/Ldr McKenna were later both awarded the OBE for their work in bringing the culprits to justice. Lt Col Scotland also received the OBE for this, and other, duties.

The Murderers and their Accessories

German Luftwaffe

General Grosch was the Luftwaffe officer directly responsible for the security and welfare of prisoners of war. He and his deputy, Colonel Waelde, were interrogated by Lt. Col. Scotland at the London Cage. A German civilian, Peter Mohr, who worked in the Kriminalpolizei and who was outraged at the murders, provided key information to the interrogators.

Breslau Gestapo

Standartenfuhrer Seetzen was involved with the Breslau Sicherheitsdienst, and arrested in Hamburg on September 28th 1945, after identification by former colleagues. He bit on a cyanide capsule whilst being taken for interrogation, and died within minutes.

Obersturmbannfuhrer Max Wielen, Breslau Gestapo Chief, was sentenced to life imprisonment on 3-Sep-47 but only served a few years before being released.

Gestapo Chief Dr Wilhelm Scharpwinkel was masquerading as a Lt Hagamann in the No 6 Hospital at Breslau when Frau Gerda Zembrodt, corroborated by Klaus Lonsky, saw Russian officers remove him at gunpoint. During the enquiry into the murders, the Russians refused to co-operate with the Allied investigation, although after much prodding they allowed Scharpwinkel to make a statement, in Moscow, during August and September 1946. Soon afterwards, Scharpwinkel disappeared and although reported dead by the Russians on 17-Oct-1947, was believed to have found a high position in the Soviet administration. He is almost certain to have died by now.

He and his associate Lux murdered Cross, Casey, Wiley, Leigh, Pohe and Hake. The next day Lux executed Humphries, McGill, Swain, Hall, Langford, Evans, Valenta, Kolanowski, Stewart and Birkland. The day after that, he executed Kiewnarski, Pawluk, Wernham and Skanzikas. On April 6th, Lux murdered Grisman, J E Williams, Milford, Street and McGarr. Long followed soon after. Lux is also believed to have killed Tobolski and Krol, who vanished in the same area as the others. Lux, with at least twenty-seven murders on his soul, died in the fighting around Breslau at the end of the war. Gunn, killed at Breslau, is likely to have been another of their victims.

All photos in the next section are copyrighted to the Imperial War Museum, which kindly gave permission to reproduce them.

Kriminalkommissar Dr Gunther Absalon investigated the escape and poked around at Sagan for some weeks. He chaired the German enquiry into the Escape and collected evidence. It is not clear what happened to him or whether or not he was involved in the murder conspiracy. Absalon, seen alive and well in Breslau in May 1946, was reported to me as (a) being hanged and (b) having died in a Russian prison in May 1948.