War often pushes human endurance to its absolute limits, demanding courage, adaptability, and unwavering resolve in the face of constant danger.

George Ray Tweed, a U.S. Navy radioman first class, embodied these qualities during World War II. When Guam fell to Japanese forces, Tweed was left behind, isolated and hunted. For an extraordinary two years and seven months, he evaded capture, surviving alone in hostile territory while relentlessly pursued. Cut off from aid and comfort, he relied on ingenuity, perseverance, and sheer willpower—never surrendering, even as the odds remained overwhelmingly against him.

Japanese invasion of Guam

George Ray Tweed had been in the US Navy for 16 years when Japan invaded Guam in December 1941. In fact, he’d lived on the island with his family since mid-1939. Family of service members stationed on Guam had already been evacuated, so when the Japanese launched their attack on December 8, the only ones on the island were sailors and US Marines, along with a few nurses.

The numerically superior Japanese quickly swamped any resistance on the part of the Americans, with the garrison surrendering on December 10. However, six sailors decided not to give in. Instead of resigning themselves to spending the rest of World War II in a Japanese prison camp, they chose to flee.

Four of them were stationed at the Radio Communications Center, including Tweed. The other two were crewmen from the USS Penguin (AM-33), a minesweeper that had been sunk by the enemy at the start of the invasion.

George Ray Tweed refused to surrender to the Japanese

When news of the American surrender reached Guam, George Ray Tweed and fellow radioman Albert Tyson knew they had only minutes before Japanese troops began sweeping the island. Grabbing pillowcases and stuffing them with a few essentials, they fled straight into the dense jungle. In their haste, however, they made a potentially fatal mistake: they forgot water. On an island where fresh water was scarce, the omission nearly sealed their fate.

Hours of hacking through rugged terrain quickly drained their strength. Dehydrated, battered, and barely able to continue, the two men finally collapsed from exhaustion. Their survival hinged on a single act of humanity. Francisco, a local Chamorro villager, discovered them and chose compassion over self-preservation. He brought them food, water, and shelter—aid that meant the difference between life and death.

The danger was immediate and severe. Japanese patrols were actively hunting for escaped Americans, and anyone caught helping them faced brutal punishment or execution. Fully aware of the risk, Francisco led Tweed and Tyson to a concealed jungle hideaway where they could remain unseen through the night. At dawn, true to his word, he returned with more supplies—an extraordinary act of bravery from a man who knew that protecting them could cost him everything.

Helping the escaped Americans remain hidden

The local Chamorro people’s help proved to be a crucial factor in terms of George Ray Tweed’s evasion of the Japanese. Without their assistance, he probably would’ve been captured and executed.

Enemy troops initially tried to get the native islanders to assist in their efforts to capture the Americans by offering a monetary reward for information. This started out as ¥10 for each American, and ¥50 for Tweed, because of his skill for repairing radios. However, nobody helped; the Chamorros hated the Japanese and only cooperated with them when threatened.

Ramping up efforts to capture George Ray Tweed

After their first week of evading the Japanese, George Ray Tweed and Albert Tyson realized that efforts to catch them were being ramped up. They moved to a new, more remote hideout: an excavated dirt shelter dug by another local, Jesus Quitugua. Another Chamorro, Juan Cruz, managed to smuggle them an old radio, which Tweed managed to get working

Tweed and Tyson survived for a few months in their dugout shelter. Meanwhile, the Japanese upped the rewards for information to ¥100 per American and ¥1,000 for Tweed, but, still, nobody turned the men in.

By this point, the other four Americans had been hidden by a Chamorro named Miguel Aguon, and Cruz helped Tweed and Tyson meet up with them. When all six were together once more, they decided their best bet for long-term survival was to split up. Each went their own way and, from this point on, Tweed was on his own.

Splitting up wasn’t the best idea

Things didn’t go so well for the other Americans after this. Three were captured almost immediately and made to dig their own graves before being executed. Tyson and another man, Machinist Mate 1st Class C.B. Johnston, held out longer, but, eventually, the Japanese discovered them hiding in a chicken coop. They shot Johnston, and when Tyson came out with his hands up, they shot him, too.

Tweed was now the last one left alive, having hidden himself in a cave. However, the enemy was pulling out all the stops to locate him. He’d also been typing out a local Resistance newsletter on a small typewriter that one of the locals had smuggled to him.

With the help of another Chamorro man, Antonio Artero, Tweed found his new and final hideout on Guam: a hidden opening at the top of a high cliff overlooking the ocean, on the northern part of the island. This was where he stayed until his rescue.

George Ray Tweed was rescued after more than two years

During this time, Antonio Artero regularly brought George Ray Tweed food and water. The latter promised to repay him for his help one day, even though the Chamorro people refused to entertain the idea of payment. Meanwhile, the Japanese had taken to torturing and executing local islanders whom they believed were withholding information about Tweed. Even in the face of such atrocities, nobody gave him up.

Tweed continued to hold out as the weeks, months and years passed. Finally, on June 11, 1944, he saw American aircraft flying over Guam. A month later, on July 10, ships got close enough for him to signal. However, instead of begging for his own rescue, he flashed them a coded message, warning them of the location of Japanese gun batteries on the island.

Only after they had acknowledged receiving this information did he ask for help.

What happened after World War II?

George Ray Tweed was rescued on July 10, 1944. He received the Legion of Merit with “V” device and the Silver Star. Following the Second World War, he not only returned to Guam to thank the locals who’d helped him, he also fulfilled his promise to Antonio Artero. The man had mentioned a dream of owning a brand new Chevrolet – and that’s exactly what Tweed gifted him.

More from us: Operation Catechism: Demise of the German Battleship Tirpitz

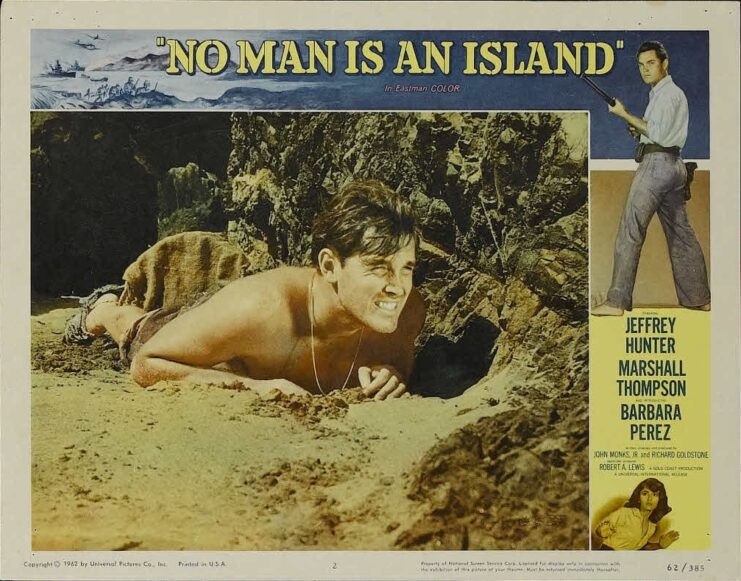

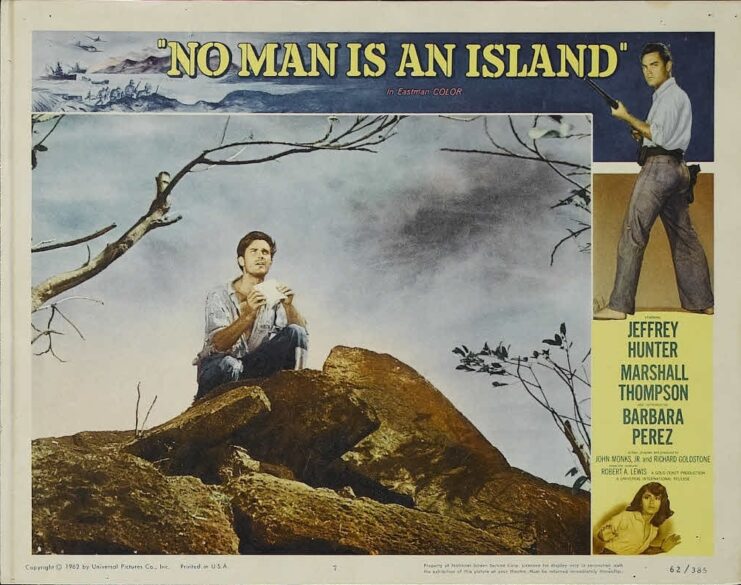

George Ray Tweed retired from the US Navy as a lieutenant in 1948, and he passed away in 1989. Prior to his death, he’d become a best-selling author for his book, Robinson Crusoe, U.S.N: The Adventures of George R. Tweed, Rm1 on Japanese-Held Guam. He also had his story portrayed in the 1962 film, No Man Is an Island, starring Jeffrey Hunter.