During WWII, the US military reluctantly deployed African-Americans. While most were put in menial roles, a few were sent to the warfront under white officers – mostly from the south in the belief that only such men could control “their blacks.”

The military was proven wrong. Even so, many African American soldiers were deprived of America’s highest distinction for battlefield valor – the Medal of Honor. Though later rectified, only one would live to see his.

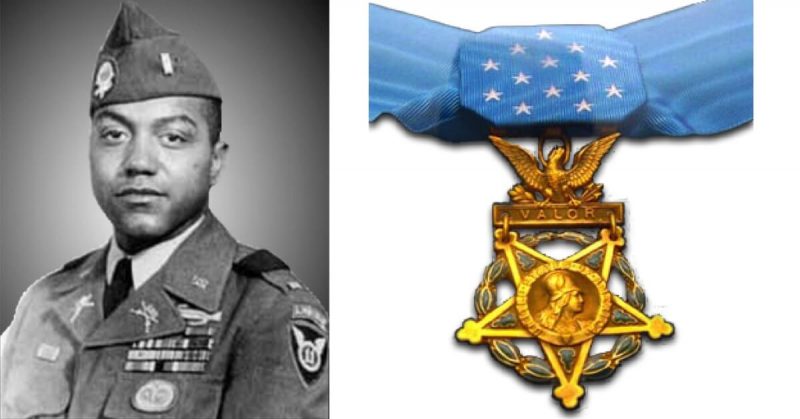

Image Source: National Archives Catalog

Vernon Joseph Baker was born on December 17th, 1919 in Cheyenne, Wyoming. Orphaned at four, he and his two sisters were raised by their grandparents.

His grandfather was a railroad worker who became the father he needed. His grandmother wasn’t so motherly, however, which was why he ended up at the Boys Town orphanage in Nebraska.

After high school, he worked as a railroad porter in Clarinda, Iowa – his grandfather’s hometown. It was awful. The discrimination he faced was incredible, but his grandfather wouldn’t let him quit because he knew how hard it was for a black man to get a job.

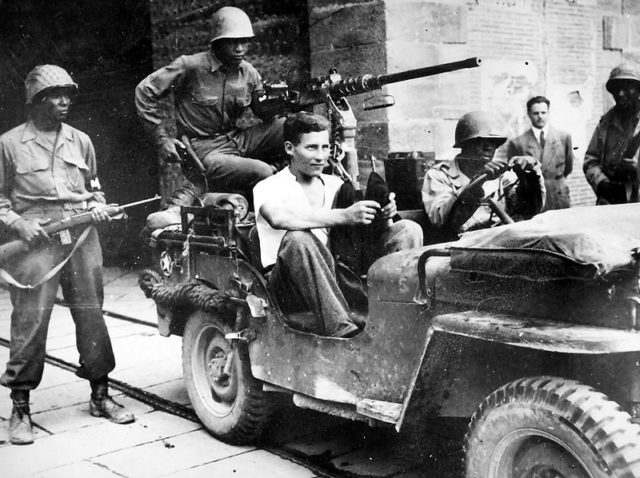

Image Source: Wikipedia / Public Domain

Baker endured till 1939 when his grandfather died. With a sigh of relief, he quit his job, but his relief didn’t last. His role model had been absolutely correct – which was why he found himself drifting from a series of menial, low-paying jobs.

By 1941, he had become an angry young man. Afraid that he might turn to crime, his sisters suggested enlisting in the military, so he did just that. It didn’t turn out well.

Baker never forgot how it went at the recruitment office in April. Behind the desk sat an unsmiling man who didn’t look too happy to see him.

“What do you want?” the recruiter barked.

As if it needed spelling out but Baker did so, anyway.

Image US Army / Public Domain

“We don’t have any quotas for you people,” was the reply.

Baker spent the next three months looking for a job but found nothing. So he decided to try a second time, but vowed that if he got the same treatment from the same man, he’d punch him.

What he got instead was an eager-looking young sergeant who pleasantly welcomed him into the office. That surprised Baker since the man was white.

“What branch of the service do you want to get into?” the man asked politely.

“Quartermaster.”

Baker leaned over and watched as the man wrote, “Infantry.”

The world had returned to normal.

Image Source: Wikipedia / Public Domain

Baker joined the Army on June 26th, 1941 and trained at Camp Wolters in Texas. Passing the Officer Candidate School, he became a commissioned 2nd lieutenant on January 11th, 1943 with the all-black 92nd Infantry Division.

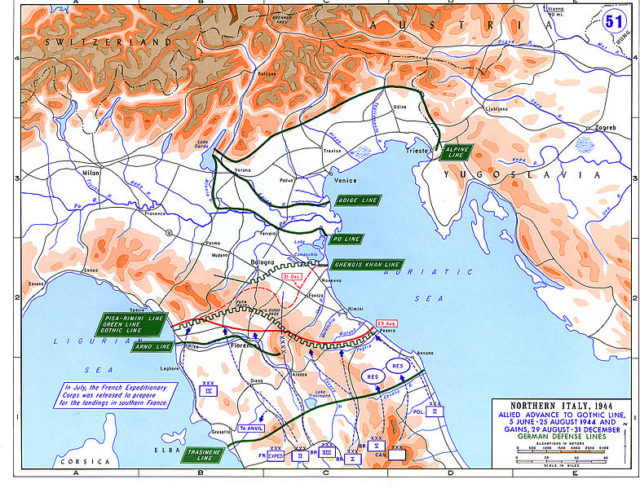

They were sent to Italy in June 1944. Four months later, Baker was shot in the arm, but rejoined his team in December near the Gothic Line – a series of German defenses along northern Italy.

The 92nd were put in reserve, but that changed the following year when they were ordered to take Castello Aghinolfi – a mountain fort. Several battalions had already tried to take it but failed.

On April 5th, 1945 it was the 92nd’s turn. Baker led 25 men from his weapons platoon and Company C’s rifle platoons toward the fort. Below it on the southern side was a draw that provided some protection.

Image Source: www.apathtolunch.com CC BY-SA 3.0

From that vantage point, Baker saw two cylindrical objects jutting out from a slit on the edge of a hill. Ordering his men to stay put, he crawled up to the slit, jabbed his M1 carbine into it, and fired away – killing the two men inside.

Moving further on, he found two German soldiers eating breakfast outside their camouflaged machine gun nest. Baker made sure it was the last thing they ate.

Company C’s Commander, Captain John F. Runyon (who was white), ran up to see if he was alright. The duo then made their way uphill looking for a way toward the fort when they surprised another German soldier. The man threw a grenade at them then ran. Fortunately, it didn’t explode. Unfortunately for the man, Baker shot him twice.

Then they split up. Baker followed a trail that turned back into the hill before descending. To his surprise, he found a car door jammed against the hillside. Realizing it was a dugout, he threw a grenade inside, but it didn’t explode.

He was about to chuck another in, when a sleepy-looking German popped his head out, wondering what was going on. He didn’t wonder long as Baker shot him then threw another grenade in. That one exploded, killing another three inside.

Image Source: Armémuseum (The Swedish Army Museum) / Public Domain

Moving further down, he found another dugout and threw a grenade in. Two men ran out into Baker’s bullets before the explosion hit.

That finally roused those in the fort, so they began firing. Baker ran back to camp where he found the captain crouched on the floor with his knees rolled up to his chin.

Runyon looked up, “Baker, can’t you get those men out there?”

“Trying the best I can, Captain,” he replied.

After several minutes of silence, Runyon sighed, “Baker, I’ll get some more reinforcements.”

Image Source: Quickload at English Wikipedia / Public Domain

Baker had seen that look before, so all he said was, “We’ll be here when you get back.”

But he knew better. Runyon never returned nor did reinforcements come. Baker managed to take out two more machine-gun positions, two observation posts, two bunkers, and a telephone line.

The following night, he led a battalion through a minefield, but it did no good – the Germans were too well defended. The 92nd eventually retreated at the cost of 19 men.

Runyon got a Distinguished Service Cross. Baker did, too, as well as a Purple Heart and a Bronze Star. Not that America changed, which was why he lost his commission. The reason? He didn’t have a college degree. Then the Korean War broke out. All of a sudden, a degree ceased to matter, so Baker got his commission back.

The Army later admitted that it had discriminated against black soldiers, so on January 13th, 1997 Baker finally got his Medal of Honor – the only one to get it while still alive.

Image Source: Wikipedia / Public Domain