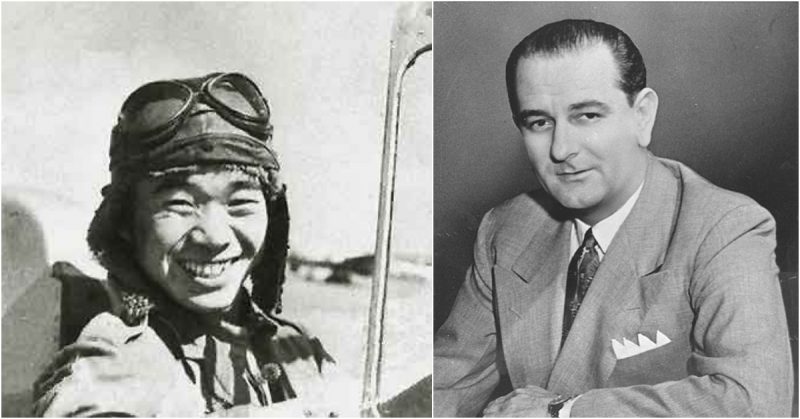

There was a certain U.S. Congressman aboard that plane by the name of Lyndon B. Johnson.

With over 60 victories and over 20 confirmed kills, Saburō Sakai was a legend among Japanese pilots. Not only was his record of victories remarkable, but he also flaunted his skills by performing a mocking air show over an Australian airbase.

As the most successful Japanese pilot of the war – and with more victories than any American pilot in the war – he had plenty of interesting stories to tell later in life. One of his most famous stories was of the time he came close to a kill that would have altered the course of U.S. history.

Lead-up to the War

Saburō came from a working family, but one with a proud military tradition. His ancestors had been samurai, although they were forced to settle as farmers due to the Meiji Restoration. Even though his family could afford to send him to school, he bailed out.

With few other options, he decided to take up his family’s traditional occupation and joined the military at the age of 16.

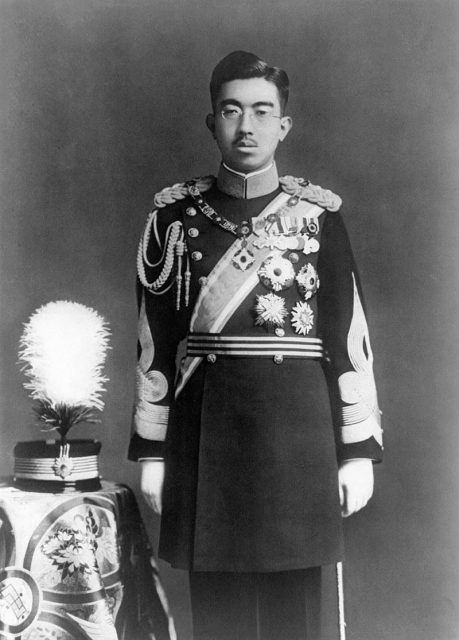

Sakai was far more successful as a military man that he had been as a student, rising quickly through the ranks. He received four promotions while serving on several battleships and soon became a petty officer. He then decided to apply to flight school and graduated first in his class. As an award, he was given a silver watch by Emperor Hirohito himself.

His first confirmed kill came not in combat against an American, Australian, or even Chinese plane, but against a Russian Ilyushin DB-3. He shot down the Chinese-piloted DB-3 in 1939 while flying a prototype of the famous Zero. Although the DB-3 was built in Russia, many of them had been lent to China to aid their fight against Japan.

He was later injured when the Chinese bombed the airfield where he was stationed. Even then, he found an undamaged plane and took to the skies in an attempt to get revenge.

Early World War 2

By the time Japan attacked the United States, Sakai was a petty officer first-class and had been given a proper Zero. He was promoted six times before he even began the most famous part of his career.

Sakai took part in the attack on the Philippines and immediately began to rack up victories. In his first action on this front, he shot down a Curtiss Warhawk and destroyed two bombers on the ground. A couple of days later, he shot down a B-17.

After being transferred to Borneo to fight against the Dutch, Sakai found himself faced with a moral dilemma. The Japanese high command had ordered all fighters to shoot down Dutch planes regardless of whether they were armed. He shot down one fighter, but then came across a civilian plane.

After the plane refused to deviate from its course, he flew close to it to get a better look. He saw a blonde woman and her child among the passengers. The woman reminded him of his former American school teacher, and he felt in his heart that he could not shoot the plane down. Instead, he waved them on and pretended he never saw them.

However, Saburō Sakai showed no mercy during the rest of the Borneo campaign, as he racked up 13 additional kills. He soon found himself engaged mostly with American and Australian forces.

Entertaining the Australians

Shortly after that, Sakai and several other top Japanese aces heard the song Danse Macabre while listening to Australian radio. The song inspired one of Sakai’s fellow aces to perform something of an airshow over an Australian base to show off. He convinced Sakai and another ace to join in.

The trio carried through with their plan the next day after an attack on Allied airfields at Port Moresby. They performed a maneuver in which they flew in three loops in a close formation. They even repeated this maneuver after getting closer to the ground (and within anti-aircraft gun range).

Surprisingly, the Australians, perhaps amused, did not fire on the three aces.

An Allied bomber flew over the Japanese base the next day and dropped the following note: “Thank you for the wonderful display of aerobatics by three of your pilots. Please pass on our regards and inform them that we will have a warm reception ready for them, next time they fly over our airfield.”

Although his commander was infuriated, Sakai never regretted this decision.

Almost Killing LBJ

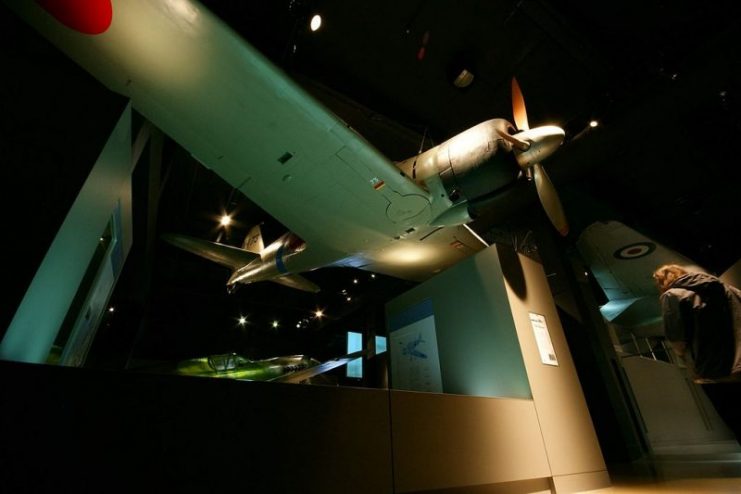

Sakai’s victories are even more impressive given that his Zero was outdated by the mid-point of the war. Although the Zeros were formidable opponents early in the war, largely owing to their speed, the Allies eventually adjusted to meet this threat.

New Allied planes were superior to the Zero in almost every way, from firepower and effective range to speed. However, Sakai continued to gain victories in his outdated aircraft.

Yet there was one particularly significant instance in which an American plane escaped from the Samurai of the Skies. On June 9th, 1942, Sakai engaged the American B-26 bomber Heckling Hare. Although he successfully crippled it by taking out its right engine, the plane managed to escape into the clouds, and he could not find it to finish it off.

There was a certain U.S. Congressman aboard that plane by the name of Lyndon B. Johnson, who had been sent on a fact-finding mission by President Franklin Roosevelt. His mission was to observe the prowess of the Zero fighter, which he certainly succeeded in doing.

Late World War 2

On August 7th, Sakai achieved one of his most impressive victories against American pilot James “Pug” Southerland, who became a famous ace in his own right. However, Sakai’s luck was soon to run out.

Later that same year he saw a formation of American planes that he believed to be fighters. Accordingly, he approached them from the rear to attack. Unfortunately for Sakai, they turned out to be SBD Dauntlesses, which have rear gunners.

Although he succeeded in shooting down two of the planes, one of the rear gunners scored a direct hit on Sakai himself.

Although he had been shot in the face and his plane was on fire, Sakai was not dead. However, he assumed he would be very soon and began to look for a ship to crash into so he could take some enemies with him.

The wound had blinded him in his right eye and left him unable to use the left side of his body. However, he found that not only could he still control the plane but also that the dive he had gone into had put the fire out. He eventually made it back to base, although he nearly crashed while landing.

Sakai was put in charge of training young pilots while he recovered as best he could (he would never regain vision in his right eye). However, he grew frustrated as Japan began to lose the war and asked to fly again. He got his wish in 1944 when he was transferred to Iwo Jima.

He was soon attacked by a squadron of 15 Hellcats while flying alone over Iwo Jima. Incredibly, he not only survived this encounter but he also returned to base without being hit a single time.

Even though his Zero was inferior to the Hellcats, he was able to avoid their fire due to his immense skill. They had to stop attacking him when he lured them towards Japanese anti-aircraft guns.

Saburō Sakai saw a few more sorties before the end of the war and eventually claimed 64 victories.

Legacy/Post-War

Saburō Sakai survived the war as a living legend. He went on to write ten books and give numerous interviews. His most famous work is Samauri of the Sky, an autobiographical text, which was turned in a movie in 1976.

To Sakai, the war was never personal. He was even on good terms with Harold Jones, the rear gunner who so nearly killed him. He eventually became a Buddhist and vowed never to kill another living creature.

Read another story from us: The Japanese Thought this Tiny Island was Empty, They were Utterly Wrong

In regards to nearly killing LBJ, Sakai said that he was only doing his duty. In fact, he considered Johnson “a real patriot deserving the highest esteem.”

He added, “I cannot but feel that President Johnson is a man of great courage and responsibility… in view of the fact that he voluntarily took part in the hazardous aerial mission over Lae, one of the strongholds of the Japanese aerial front line in the South Pacific at that time.”

Sakai died in 2000 at the age of 84 at a U.S. base in Japan due to a heart attack. He had been the guest of honor at a formal dinner that night.