The most iconic images of European fortifications are the castles of the Middle Ages – towering constructions of stone made obsolete by the arrival of gunpowder. However, some of the most spectacular fortifications ever built occurred during the age of concrete and high explosives. They played an important part in WWII.

The Maginot Line

Built between 1929 and 1938, the Maginot Line is remembered as one of the most spectacular follies in military history.

Stretching along France’s eastern border from Switzerland to Luxembourg, the Line consisted of concrete forts at three-mile intervals, with smaller blocks in between. The forts had garrisons of 200-1,200 men while the smaller blocks contained 12-30. Buried for extra protection, the only part of the defenses above ground were the gun emplacements and observation domes. The larger sites had barracks and kitchens as well as their own power plants and electric railways to transport men and supplies.

For diplomatic reasons, the Maginot Line did not extend along the border with Belgium. When Hitler invaded France, he sent German forces through the Low Countries, avoiding the Maginot Line altogether. Due to that, the Line gained a reputation as an analogy for expensive efforts that offer a false sense of security.

An argument can be made that the Line served its purpose. By channeling German forces north, it allowed the rest of the French army to face them in a specific and limited area.

Most of the Maginot Line never saw military action. Following the Battle of France, the forts surrendered.

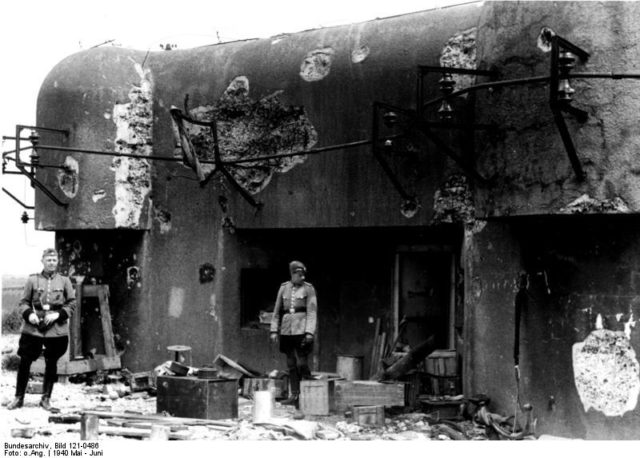

Eben Emael

Although the Maginot Line did not extend all the way to the coast, other defenses helped to fill the gap.

Fort Eben Emael was part of the Belgian defense system around the Albert Canal. Built between 1931 and 1935, it was the biggest of four forts around Liege and at the time was the largest concrete fort in the world. Occupying a large hill overlooking the canal, the fortress was built of reinforced concrete, with gun cupolas protruding from the hillside. In 1940, it had a garrison of 1,200 men – 1,000 to operate its guns and 200 technical and support staff.

Eben Emael fell to one of the most daring German operations of WWII. In the opening hours of Hitler’s western advance, 85 paratroopers led by Rudolf Witzig landed on the roof of the fort. They destroyed the gun emplacements, blew the entrances, and forced the surrender of a garrison that vastly outnumbered them.

The Siegfried Line

Hitler’s answer to the Maginot Line was the Siegfried Line, also known as the West Wall.

From 1936 to 1939, a vast number of cheap and forced laborers traveled to west Germany. There they built concrete bunkers, dug trenches, laid out row upon row of “dragon’s teeth” anti-tank barriers, and made other preparations for the defense of Germany.

The Siegfried Line was begun in secret. Part of its purpose was as a deterrent, and its existence became widely known. It was roundly mocked by the French and British as a cheap imitation of the Maginot Line. British Soldiers marching to war in 1939 sang about hanging out their washing on the Siegfried Line.

The line made it hard to invade Germany from the west and so helped Hitler buy time while he invaded Poland and prepared the same for France. Once he had conquered the French, it became unnecessary. Weapons and supplies were moved out of the fortifications, soldiers left, and the doors were locked.

Four years later, as the Allies fought their way east, the situation changed. German troops hurried to reoccupy the line, replacing rusted parts and cutting back the plants over-running open ground. For six months, Allied troops were held up on the line, fighting fierce battles while their comrades found other routes into Germany.

The Czechoslovak Border System

As Europe inched toward war during the 1930s, the government of Czechoslovakia became very nervous about Germany’s intentions. In 1936, they began constructing concrete defenses along their border. The first stage was due to be completed in 1941-2, with the whole project finished by the early 1950s.

In September 1938, the border system included 264 concrete forts and strongholds as well as 10,014 pillboxes. Then came the Sudeten Crisis. The other powers allowed Germany to occupy vast areas of Czechoslovakia as part of the Munich Agreement.

The territory containing the defenses had fallen to the Germans without a fight. They used the concrete forts as targets on which to experiment and practice for the Maginot Line and Belgian defenses. After the fall of France, some components were taken west, to be reused in the Atlantic Wall.

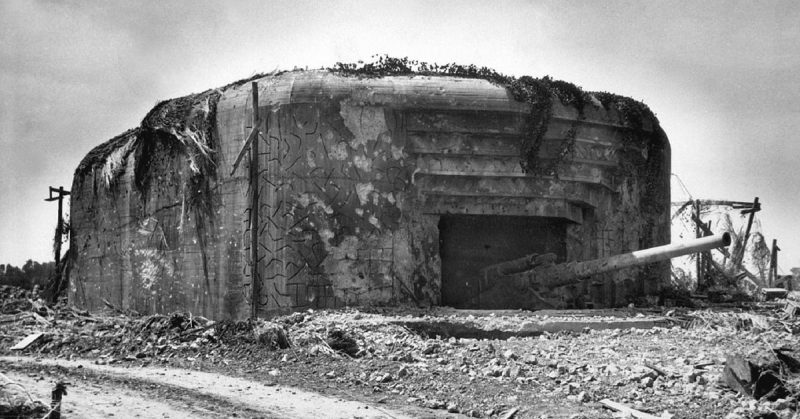

The Atlantic Wall

Having conquered much of western Europe, Nazi Germany set about defending it. To do so, Hitler ordered the construction of a defensive system along the west coast, running from the northern tip of Norway to the south of France.

The Atlantic Wall was a colossal undertaking. It included massive coastal guns, forts garrisoned by up to 60,000 men, and thousands of miles of smaller defenses. Nearly a million French laborers were conscripted for its construction, and thousands of German soldiers manned the defenses.

Hitler’s propaganda continually emphasized the strength of the Atlantic Wall. However, when Field Marshal Erwin Rommel was sent to oversee the Wall in early 1944, he concluded it was not adequate. Having fought the Americans and British in North Africa, he used his experience to improve the defenses.

It was too late. When the Allied forces landed on D-Day, the focused power of their attack punched through the Atlantic Wall in hours.

Sources:

Nigel Cawthorne (2004), Turning the Tide: Decisive Battles of the Second World War

Richard Holmes, ed. (2001), The Oxford Companion to Military History

James Lucas (1996), Hitler’s Enforcers: Leaders of the German War Machine 1939-1945

Charles Whiting (1999), West Wall: The Battle for Hitler’s Siegfried Line