Did the Japanese really conquer the Philippines during the Second World War? Well, they certainly defeated the American and Filipino forces following the fighting that defined their invasion, and they also toppled the nation’s government. However, by the time American Gen. Douglas MacArthur arrived to retake the Philippines in October 1944, the Japanese only controlled 12 out of 48 provinces, due to resistance by those living in the archipelago.

Philippines Campaign (1941-42)

The Philippines Campaign of 1941-42 saw the American and Filipino forces come together to fight the Japanese for control of the country. Some 151,000 Allied troops went up against just shy of 130,000 enemy soldiers, who brought with them a staggering 541 aircraft, on top of 90 tanks.

Launching their invasion by sea from Formosa (modern-day Taiwan), the Japanese were aware of the strategic importance of the Philippines, which would allow them to grow their sphere of influence in the South Pacific, while also providing much-needed supply bases and staging areas to prepare troops for operations against Guam and the Dutch East Indies.

The Japanese were also aware of how important the country was to the Americans. Not only would it be possible for the US Army to use the Philippines as a base in the Pacific Theater, officials could use the country to launch campaigns in the Solomon Islands by deploying troops to nearby areas.

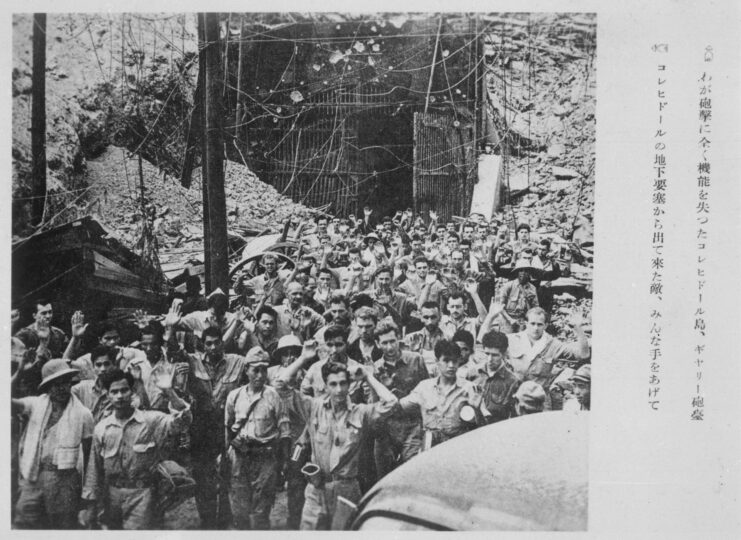

Immediately following the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Japanese launched their invasion of the Philippines, beginning with the bombing of Tuguegarao and Baguio. By early January 1945, the Japanese had captured Manila, and Bataan was largely under their control by April. Try as they might, the Americans and Filipinos were unable to make any headway, with US Gen. Jonathan Wainwright eventually announcing their surrender via radio.

What followed was the infamous Bataan Death March, the grueling 65-mile march that resulted in the deaths of between 5,500 and 18,650 prisoners of war (POWs).

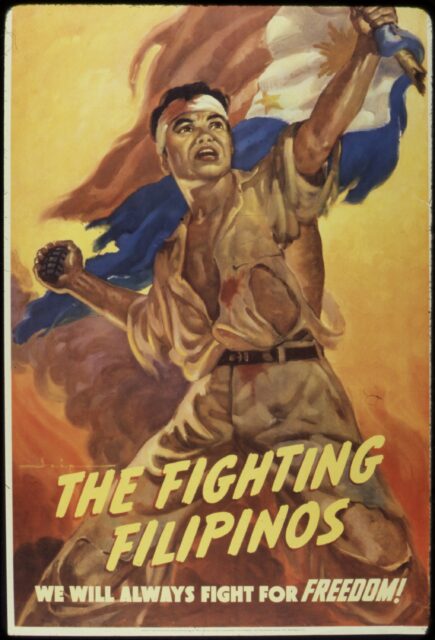

Fighting Filipinos

Following the surrender of the Philippines to the Japanese in spring 1942, a number of guerrilla groups sprang up to fight against the occupiers. US and Filipino officers and soldiers, local leaders, and citizens across the country led groups, ranging from just a hundred or so members to thousands of resistance fighters.

One skill these guerrilla groups had was developing underground networks. They organized local intelligence gathering, secret radio transmitters and had informants in the Second Philippine Republic – the Japanese-backed puppet government.

The US recognized 277 guerrilla groups and 260,715 fighters, most of whom were associated with the Philippine Commonwealth. In reality, there were likely well over one million fighters resisting the Japanese. Douglas MacArthur was in awe of their success, and the tactics learned from these fierce guerrilla fighters continue to influence the US military to this day.

Hunters ROTC

Some of the first guerrilla fighters to organize during the Japanese invasion and occupation were the Hunters ROTC. Cadets with the Philippine Military Academy who’d been too young to join the US Army Forces Far East (USAFFE), led by Terry Adivoso, met up and began recruiting other cadets and willing fighters who wanted to do their part for the war effort.

Originally numbering around 300, the Hunters ROTC operated on southern Luzon Island, the country’s largest northern Island, and around Manila, the Philippine capital. In one early action, they raided the Japanese-occupied Union College and absconded with 130 M1917 Enfield rifles.

Throughout the Japanese occupation, the Hunters ROTC provided intelligence to Douglas MacArthur, partook in propaganda activities, protected civilians and fought in several engagements, including the raid on New Bilibid Prison (NPR) in June 1944. This particular event showed just how aggressive these guerrillas were, with them successfully breaking into the prison, freeing fellow fighters and stealing over 300 rifles from the facility’s armory.

Hukbalahap

Another guerrilla group – and one that worked with far less coordination with the American forces – was the Hukbalahap. They were a Communist group who’d hoped to spread their message and gain control of the Philippines after the Japanese had been defeated. Their full title was Hukbong Bayan Laban sa Hapon – the People’s Army Against the Japanese.

They originated with just 500 members and grew to a complement of between 15,000 and 20,000 by the middle of World War II, with an additional 50,000 fighters in reserve. Similar to other guerrilla groups, these fighting Filipinos obtained equipment by stealing it from Japanese bases. However, the majority of organizations operating within the Philippines viewed the Hukbalahap as terrorists, whereas the group’s members viewed themselves as freedom fighters.

Speaking about his interactions with the guerrillas, American Ray C. Hunt recalled, “My experiences with the Huks were always unpleasant. Those I knew were much better assassins than soldiers. Tightly disciplined and led by fanatics, they murdered some Filipino landlords and droves others off to the comparative safety of Manila. They were not above plundering or torturing ordinary Filipinos, and they were treacherous enemies of all other guerrillas.”

The fighters operated against the Philippine government and Americans for years following the conclusion of the war, in an event known as the Hukbalahap Rebellion. The fighting, which occurred in two phases, was eventually quelled through military action and government reform.

Filipino guerrillas teamed up with the Allied forces

By late 1942, the Allied Intelligence Bureau and US military were in contact with many of the guerrilla groups operating in the Philippines, and were aiding their missions by sending supplies and providing intelligence. The majority of the those they worked with were actually led by USAFFE officers and soldiers who’d risen up to lead the resistance in the jungle, mountains and urban regions.

One guerrilla group the Americans worked closely with was the Wha-Chi, a group of Chinese-Filipino fighters who fought to protect the ethnic Chinese from Japanese cruelty. They numbered around 700 men. Various rebel groups in the Visayas, the central area of the Philippines, worked with varying degrees of coordination with US forces. The Black Army, led by Ruperto Kangleon, played a crucial role in supporting US operations, especially Douglas MacArthur’s invasion of Leyte Island.

One captain was Nieves Fernandez, the only female commander in the Philippines and a member of the Waray people. A former schoolteacher, she commanded 110 guerrillas, and specialized in improvised weaponry, even operating a homemade gun. A skilled marksman, she was responsible for taking out 200 enemy soldiers, which led the Japanese to put a 10,000-peso price on her head.

In one remarkable mission, soldiers with the 6th Ranger Battalion and Alamo Scouts, along with Filipino guerrillas, freed Allied prisoners of war (POWs) from a camp near Cabanatuan City. Of the 133 Americans who were involved, only two were killed, and around nine injuries were reported among the 250-280 Filipinos who’d participated in the fighting.

Moro population

In the Southern Philippines, mostly on the large island of Mindanao, the Moro population had been fighting an ongoing war with the Philippine government. Their relationship with the United States was also less than peaceful, due to the Moro Rebellion of 1899-1913. As such, they had no allegiance with either the Americans or the Filipinos.

Their guerrilla groups were often quite successful, if not incredibly ruthless. One particular organization, which touted 20,000 members and was led by Datu Gumbay Piang, was called Moro-Bolo. Their flag featured an illustration of a bolo, a traditional Philippine knife, and a kris, a fabled sword made popular over the centuries by Muslims in the Philippines and Indonesia.

Another Moro guerrilla group, led by Datu Busran Kalaw, was approached by the Japanese, who sought to play on their ethnic ties to gain solidarity. In response, Kalaw attacked the enemy, who sent a large force to crush the stubborn Moros… None of the Japanese troops survived.

Using guerrilla tactics to develop the US Special Forces

American officers who helped lead the guerrilla forces in the Philippines later used what they learned from these Filipino fighters to form and develop the US Special Forces in the post-war period.

Russell William Volckmann, a US Army officer who’d served during the Philippine Campaign, escaped certain death by moving through Japanese lines and became the commander of the US Army Forces in the Philippines – Northern Luzon. He admired the tactics used by the guerrilla groups fighting throughout the Philippines and even tried to recruit organizations.

More from us: The Battle of Wake Island Lifted the Spirits of the American Public

Following the Second World War, Volckmann wrote several Army field manuals about guerrilla warfare. Along with Wendell Fertig and Aaron Bank, he founded the Special Forces – better known as the Green Berets. Known for their unconventional warfare, these elite soldiers are among the most skilled in the US military.