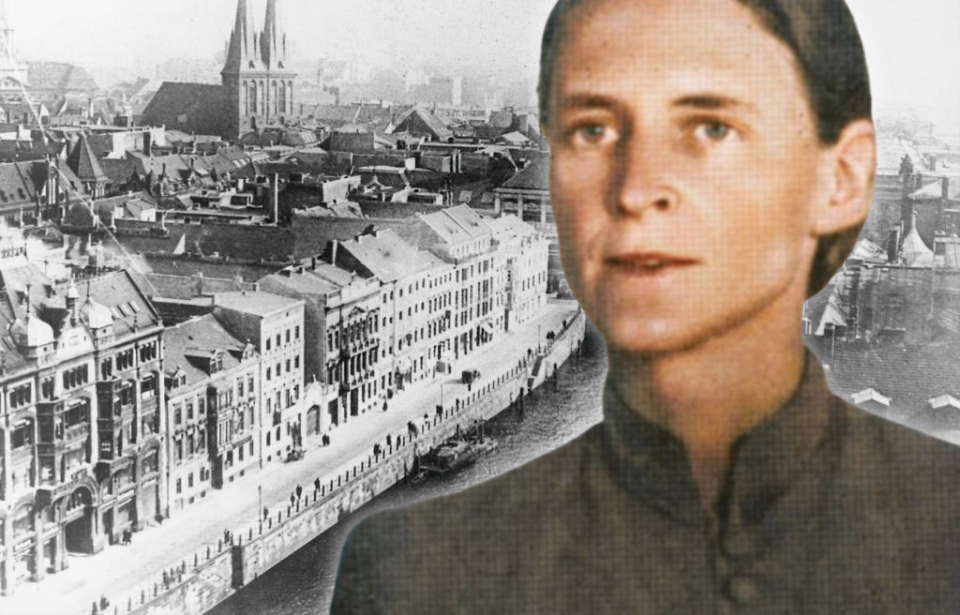

During the turmoil of World War II, as the Führer’s forces tightened their grip on Europe, a few courageous individuals chose resistance over submission. Among them was Mildred Fish-Harnack, an American scholar who refused to flee Germany and instead joined the underground fight against the Nazi regime. Working in secret, she helped organize resistance networks, pass intelligence to the Allies, and support those targeted by Nazi persecution.

She knew the risks were immense—capture meant certain death—but she never wavered. Her unwavering courage and moral conviction made her a symbol of quiet defiance, standing for freedom and justice even when surrounded by tyranny.

Mildred Fish-Harnack’s mother was a major influence

Mildred Fish-Harnack was born on September 16, 1902, in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Raised in a modest household that often faced financial hardships, she drew inspiration from her mother, Georgina, who was a staunch supporter of the women’s suffrage movement. Georgina, a self-taught stenographer and typist, instilled in Mildred both a strong sense of justice and a deep appreciation for literature.

Mildred’s passion for English grew during her years at West Division High School, leading her to pursue higher education at George Washington University and later at the University of Wisconsin. While studying, she delved into the works of Walt Whitman and Ralph Waldo Emerson, whose ideas left a profound mark on her literary development. It was during this formative period that she also deepened her commitment to social justice causes.

Making the move to Germany

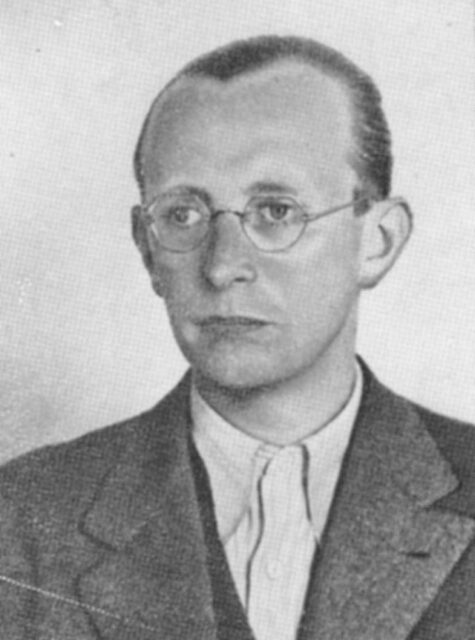

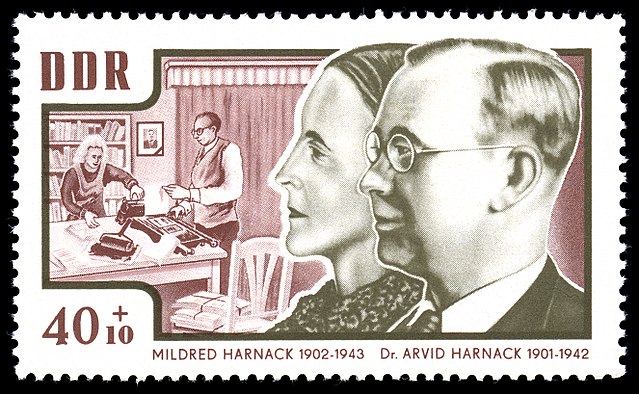

In 1926, Mildred Fish married Arvid Harnack, a German economist she had met while studying at the University of Wisconsin. Not long after their marriage, she moved with him to Germany, where he continued his academic career. Mildred also pursued further education, enrolling at the universities of Jena and Giessen to continue her studies.

When she arrived, Germany was already beginning to fall under the growing influence of the National Socialist German Workers’ Party. She witnessed its rise firsthand, as many of her professors and classmates openly supported the Nazi movement. Despite the political shift around her, Fish-Harnack remained dedicated to her academic path and later accepted a position as an assistant lecturer at the University of Berlin, where she taught English and American literature.

Her classes covered works by prominent authors like Theodore Dreiser and Thomas Hardy. She quickly earned a strong reputation for her teaching skills, and her enthusiasm for literature made her a favorite among her students.

Pursuing a career in literature

Mildred Fish-Harnack’s writing career flourished after her move to Germany, where she became known for her insightful essays on American literature. Her sharp writing style and profound analysis garnered much acclaim, with some comparing her work to that of the renowned author Thomas Wolfe.

Her essays were published in prominent German literary journals, where she subtly voiced opposition to the growing authoritarianism in Germany. This earned her respect within intellectual circles. Mildred also became interested in the Soviet Union, particularly the more progressive rights afforded to women there compared to those in the United States. Together with her husband, Arvid, they held private discussions on the Soviet economy, educating their students on the subject.

However, her increasing vocal opposition led to her losing her job at the University of Berlin. Shortly thereafter, she and Arvid became involved in the “Red Orchestra,” an underground resistance group committed to opposing Nazi rule.

Red Orchestra

The Red Orchestra was one of the most significant underground resistance networks to emerge within Nazi Germany during the 1930s. Made up of government insiders, artists, academics, and ordinary citizens, aimed to undermine the regime’s crimes and aid those it sought to destroy. Through acts of espionage, secret communication, and the distribution of anti-Nazi literature, the group fought to awaken German society to the truth behind the Führer’s propaganda. The group also played a crucial role in helping Jewish individuals escape persecution.

Operating in small, decentralized cells during the Second World War, the Red Orchestra was able to function for years under extreme secrecy. Despite eventual infiltration by the Gestapo, many members continued their work undeterred, driven by a deep belief that freedom and conscience were worth any price. Their bravery remains a powerful reminder of resistance in the face of totalitarianism.

Mildred Fish-Harnack was heavily involved in the Red Orchestra

Mildred and Arvid Fish-Harnack were active in the Red Orchestra, with their fluency in English and German being a particular asset, as this allowed the group to communicate with Allied intelligence agencies. They participated in typical underground activities, such as distributing leaflets, and even connected with Lt. Harro Schulze-Boysen, a left-wing publicist and Luftwaffe officer who secretly documented German military efforts and forwarded them to the Soviets.

Among the couple’s most notable efforts with the Red Orchestra involved them doing the same thing, filtering German military plans to the Red Army, which, if caught, would have undoubtedly led to their immediate executions. There’s also evidence Fish-Harnack aided the Red Orchestra’s efforts to help Jews flee Germany. Along with sheltering them, she secured false documents and safe passage out of the country.

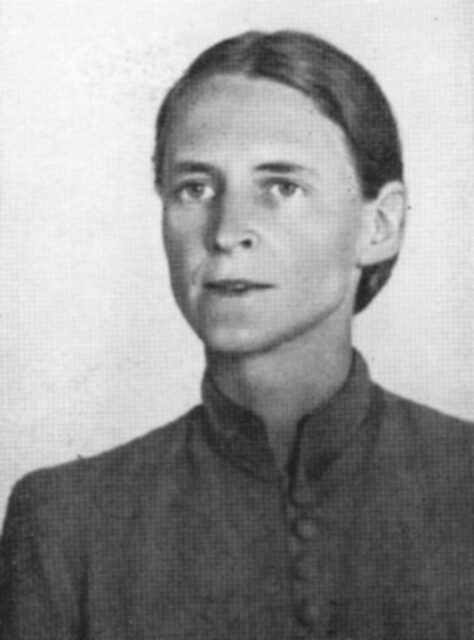

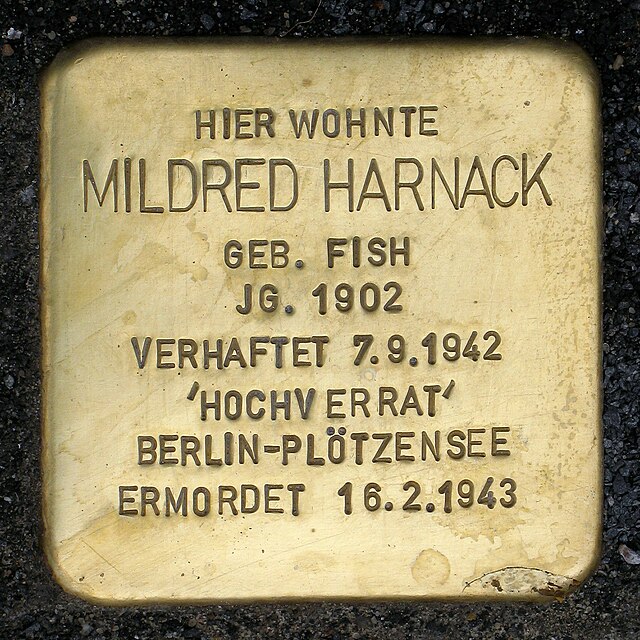

Mildred Fish-Harnack was executed for her Resistance work

Mildred and Arvid Fish-Harnack’s involvement with the Red Orchestra led to their arrest by the Gestapo on September 7, 1942, while they were vacationing on the Baltic Sea. How did the authorities uncover their activities? The Funkabwehr had decrypted messages and intercepted radio transmissions detailing the extent of their espionage.

Initially sentenced to six years in prison, the Führer deemed the punishment too lenient and ordered a retrial. At the second trial, Mildred received a death sentence, which was carried out by guillotine at Berlin’s Plötzensee Prison on February 16, 1943.

Reportedly, her final words were, “Und ich habe Deutschland auch so geliebt,” meaning, “And I, too, so loved Germany.” Despite all she endured and the oppressive regime, she maintained her love for Germany and dreamed of liberating its people from tyranny.

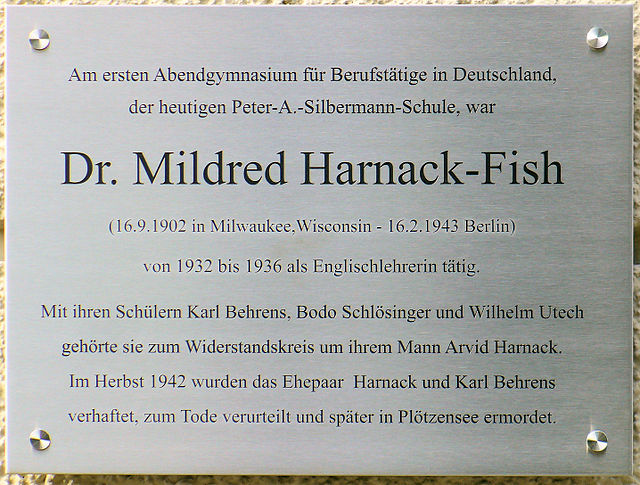

A legacy that continues to be honored

Although news of Mildred Fish-Harnack’s execution surfaced after the war, many details remained unknown to the American public. U.S. authorities conducted a secret review to determine whether her death could be considered a Nazi war crime. While her courage and resistance work were recognized, the investigation concluded that her espionage trial was “legally justifiablee” under German law. As a result, the case was quietly closed, leaving her extraordinary sacrifice and accomplishments largely forgotten for many years.

More from us: Josefina Guerrero: The Philippine Spy Who Used Her Illness to Help the Allies Liberate Her Country