What did Operation K entail?

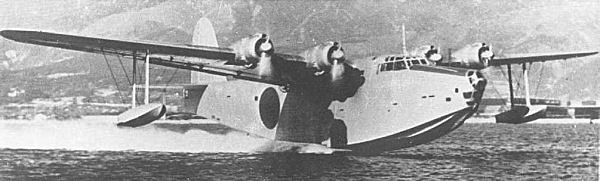

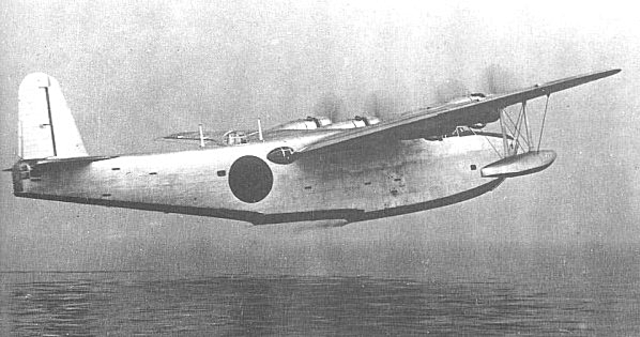

Operation K was set for the night of March 4, 1942, and was supposed to involve five massive long-range Kawanishi H8K flying boats. But because of logistical problems, only two aircraft were ultimately available for the mission.

These planes were originally earmarked for bombing runs against mainland U.S. targets like California and Texas, but first, the Japanese wanted to check on the repair progress at Pearl Harbor. The H8Ks were ideal for reconnaissance, and since each could also carry four 550-pound bombs, they had the ability to further disrupt the Pacific Fleet’s recovery efforts.

This mission was historic because it became the longest-distance bombing run ever carried out by just two planes, and it ranked among the longest bombing missions ever flown without fighter escorts. The round-trip journey from the Marshall Islands to Pearl Harbor and back covered more than 2,000 miles. To make this enormous trip possible, the Japanese placed fuel tanks at the French Frigate Shoals, where the flying boats could refuel before making the final 500-mile push toward their target.

Unable to approach Hawaii by sea

Kicking off Operation K

Ahead of Operation K’s launch, U.S. intelligence tracking Japanese movements spotted H8K flying boats being readied for action and passed warnings to naval leadership on Oahu. Those alerts, however, received little attention. The mission itself was led by Lt. Hisao Hashizume, flying the lead aircraft, with Ensign Shosuke Sasao at the controls of the second. Compounding the risk, submarine I-23—assigned to relay critical weather reports—had become lost days earlier, depriving the crews of vital situational information.

As the aircraft approached Hawaii, radar installations on Kauai detected them, prompting an immediate defensive response. PBY Catalina patrol aircraft and P-40 Warhawk fighters were launched to intercept. Thick cloud cover obscured the Japanese planes from clear visual contact, but it also limited visibility for everyone involved. Amid the confusion, a navigation error caused the two flying boats to separate, disrupting the timing of their attack.

The lead H8K released its bombs on a hillside near a Honolulu school, breaking windows but causing no casualties. The second aircraft never reached Pearl Harbor and instead jettisoned its ordnance into the sea. With the mission in disarray, the two planes withdrew independently, eventually touching down at separate airfields in the Marshall Islands.

What was the outcome?

The main result of Operation K was that the United States discovered that the Japanese could still enter its airspace and leave without being stopped. The US Army and Navy blamed each other for the nighttime explosions near the school. The mission also caused concern about possible more Japanese attacks on the US.

More from us: Debunking Myths About the Japanese Attack on Pearl Harbor

Though a follow-up was planned for a few months later, it was eventually canceled because the Americans realized the Japanese were using the French Frigate Shoals as a base and had increased patrols in the area.