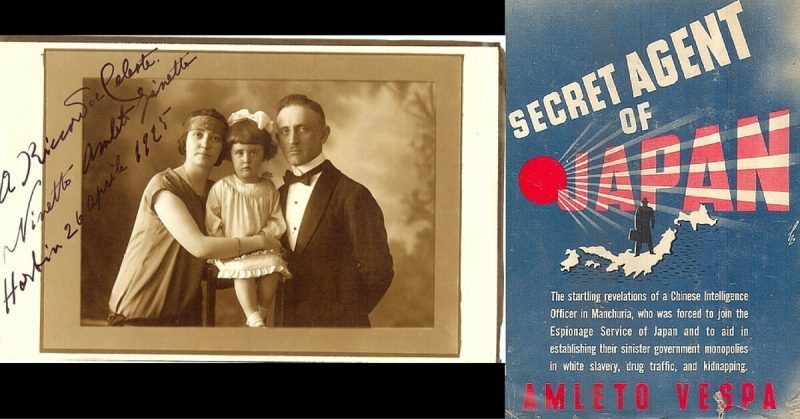

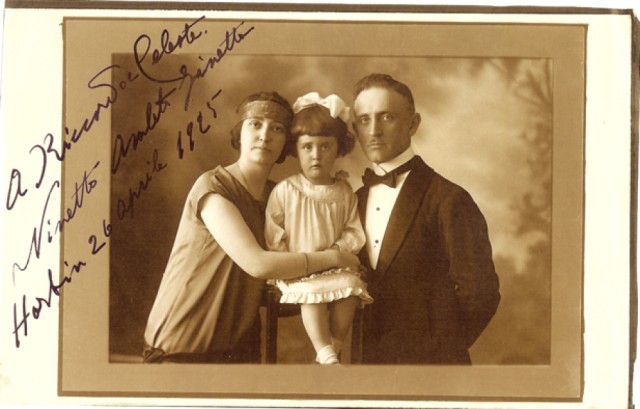

Amleto Vespa was one of the genuine adventurers of the first half of the twentieth century. It is important to stress that almost all sources of Vespa’s life come from his sensationalist autobiography titled Secret Agent of Japan: A Handbook to Japanese Imperialism that was published in 1938. The book is to be read with some caution, but nevertheless brings an interesting insight into the relationship between crime and the secret services during the Japanese occupation of China.

Born to a poor Italian family in L’Aquilla, Abruzzo region, he abandoned his family home to become a soldier of fortune in the Mexican Revolution where he fought Emiliano Zapata’s rebels. The revolution occurred in 1910 and it lasted for ten years. After Mexico, he embarked on a journey to China in 1920, where he worked for a Chinese warlord called Zhang Zuolin. Zhang was indeed a powerful warlord who controlled Manchuria prior to the Japanese invasion.

By some, Zhang was the link between China and Japan as he served as a Japanese proxy for their interests in Manchuria. Apart from Japanese sponsorship, he financed his war effort through gun running and the drug trade, which became Vespa’s responsibility.

The Chinese warlord lost domination over Manchuria after a crushing defeat against the Chinese Nationalists led by the famous Chang Kai-shek and sponsored by the Soviet Union. Even though he served well as their agent, after this defeat the Japanese assassinated the warlord in a bomb attack.

The conflict between the Nationalists and Zhang was directed by Moscow and Tokyo, who still had some unfinished business after the Russo-Japanese war in 1905, which established Japan as the great power of the Far East.

Meanwhile, Vespa was trying to stay under the radar. The Italian consulate of Tianjin had issued a warrant for his arrest and deportation on charges of smuggling guns and narcotics. With the little help of his Chinese friends, he managed to avoid deportation by gaining Chinese citizenship in 1924.

After the death of his patron, Zhang Zuolin, the Italian was down on his luck. In the meantime, his wife gave birth to a boy and a girl, named Italo and Guinevere. Vespa’s wife was, according to his own testimony, a Polish countess of some sort, who came along with him to China.

By 1931, the Japanese felt that they were losing their influence in Manchuria and in 1931, they sabotaged their own railway track (unsuccessfully, though) near the Chinese city of Mukden and used the event as a pretext for the invasion.

After the Mukden Incident and the establishment of the Japanese puppet state ― Manchukuo, Vespa’s family was detained by the Imperial Army while he managed to escape to Harbin which was under Chinese control. Harbin was at that time a cosmopolitan Chinese city and the centre of the Chinese Eastern Railway administration controlled by the Soviets as a part of the much larger Trans-Siberian Railway. The city fell just a few days after the initial invasion.

Vespa negotiated the release of his family and in exchange accepted to work as a Kempeitai secret agent. Kempeitai, the notorious Japanese secret police, wanted to use Vespa’s skills since he was very well connected in the Manchurian criminal underground. Even though Vespa considered himself an admirer of Benito Mussolini and a fascist, he disliked the Japanese and their rule over Manchukuo and criticized them throughout his book. He also insists that he was forced to work for the Kempeitai.

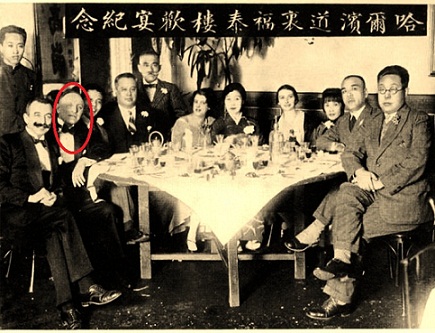

He was given a task by the head of the secret police in China, referred to in the autobiography only as “The Japanese Prince”, to compile reports on the wealthy international citizens of Harbin. Harbin was a multicultural trading city on the border between China and Russia. Besides from the Chinese, the city was populated by Jews, White Russian emigres, Germans and even Americans.

The Japanese wanted a complete intelligence report on the foreigners in the city which was at time swarming with spies. They also wanted to confiscate the property of the rich merchants and use it to finance their war effort, since the Japanese government made it clear that the colony of Manchukuo needed to be economically self-supporting. Among other tasks, he was responsible for recruiting gangs to sabotage the Soviet railway in the region.

In his book, Vespa stated that the Japanese had taken over the drug trade and other criminal activities such as prostitution and gambling during their rule and that the opium production dramatically increased in a period between 1932 and 1937.

He reported that during that time Harbin alone held 172 brothels, 56 opium dens, and 192 stores which sold narcotics of various kinds. Vespa implied that the Japanese were conducting a policy of exporting opium via Navy vessels along the Chinese coastline and on principal Chinese rivers.

Japanese consulates in Chinese cities which weren’t under direct military control also participated in the drug trade. Besides from the obvious financial reason for this campaign, its aim was to demoralize the local population by promoting drug addiction. They wanted to pacify the Chinese and divert them from resisting their tyrannical rule.

Even though the situation seemed well organised, in reality, the profit was divided among five Japanese security agencies operating in Manchukuo. They often fought among themselves, as the money was often not used for the benefit of the war effort, but was diverted for the personal gain of high ranking individuals.

His book contains evidence that the Japanese secret agents were instructed to prevent complaints and petitions filed by the local population from reaching the members of the international commission sent by the British to investigate the Mukden incident. It was called the Lytton Commission, for it was headed by the second Earl of Lytton of the United Kingdom.

Nevertheless, the commission concluded that the incident was irrelevant for the invasion and that the Japanese forces should withdraw from China, for they had no legal right to occupy and establish a presence on Chinese territory.

Vespa also witnessed and described an another peculiar event concerning the city of Harbin and the kidnapping and death of Simeon Kaspe by the Russian paramilitary fascists in August 1933. Simeon Kaspe was a son of a Jewish hotel owner in Harbin and a French citizen. He was kidnapped and held for ransom by the members of the Rodzaevsky gang.

The Japanese withheld information, even though they were capable of tracking Kaspe, for they had connections with the Russians living in the city, who were all opponents of the Soviet Union and mainly remnants of the White Russian Army defeated in the civil war, ten years earlier.

The French strongly advised Kaspe’s father not to pay the ransom of 100,000 dollars as they were working on the investigation. When foreign diplomatic pressure obliged the Japanese authorities to arrest the kidnappers, the gang executed Simeon Kaspe.

The perpetrators were arrested quickly after and a false trial was held. After a series of legal violations, that included the execution of the Chinese judge who initially sentenced the members of the gang to prison, they were pardoned. The amnesty came after an intervention by Konstantin Rodzaevsky himself who justified the crime as a political act against communism, which proved to be sheer nonsense.

In his book, Vespa included many similar cases that involved the Japanese authorities and various members of the criminal underground in acts of blackmail, assassination, kidnapping and extortion. He died in 1941, under unknown circumstances. The most probable theory is that he was shot by the Japanese, possibly because of his book.