In 1942, four Polish prisoners at Auschwitz had had enough. They wanted to escape, but if they did (regardless of whether or not they succeeded), ten fellow inmates would be executed for each of them. Forty lives for four men was too much to bear.

So they decided to leave. There was no shootout, no digging, no sneaking, nor secrecy involved. They simply drove out of the gates which the German guards obligingly opened for them. After WWII had ended, the Polish government rewarded the man responsible for this unique exit by throwing him in jail.

That man was Kazimierz “Kazik’ Piechowski, who was born in Rajkowy, Poland on 3 October 1919. One of his earliest memories was at the age of 10 when he and a German friend went to the town of Malbork (now in Poland but then in Germany).

The two swam across the Vistula River into German territory and admired the Malbork Castle while speaking in Polish. A police officer arrested them for being illegals, and after spending the night in jail, Kazik’s father bailed them out the next morning.

Fortunately, the senior Piechowski knew about his son’s love of travel and adventure, so Kazik wasn’t punished. That same year, his very love of adventure inspired him to join the Polish Boy Scouts – an act that would destroy him.

Poland was redefined in the aftermath of WWI, and Scouts placed a tremendous emphasis on patriotism. So when the Nazis invaded in 1939, the last thing they wanted was an organization devoted to a Polish national identity.

The Scouts were declared a criminal organization and all its members were, therefore, criminals. As the Germans drove into his town of Tczew, they rounded up the Scouts and started shooting them. The 19-year-old Kazik watched as many of his friends were mercilessly slaughtered, even those many years younger than himself.

Kazik wasn’t shot. He was instead put to work clearing the damaged section of the railway bridge which spanned the Vistula River he had swum across. It wasn’t the Germans who had blown it up, it was the Polish military in their failed attempt to prevent the Germans from crossing.

On November 12th, he and another Scout escaped and fled toward the Hungarian border, hoping to make it to France to join the Free Polish forces gathering there. The two made it as far as the border, but never crossed it.

They were caught and spent the next several months in a series of prisons. The first was at the Gestapo prison in Baligród. There they were told that while they should be shot, the Gestapo had something far more interesting in mind for them.

The Gestapo kept their word. Kasi was later transferred to the prison at Sanok, then to Montelupich in Krakow, and from there to Nowy Wiśnicz. His final stop was at Auschwitz on 20 June 1940 where he became inmate number 918.

There were two types of jobs in the camp: those indoors and those outside. The latter had higher death rates because the people had to work in all weather conditions and temperatures with little food and no medical care. Kazik worked outside.

To maintain the prison with less staff, the Schutzstaffel (SS) recruited prisoners – preferably those with a sadistic streak. In return for certain privileges and better treatment, these monitored and controlled their fellow inmates which sometimes involved torturing and killing them. This special group was called kapos.

Kazik’s kapo was Otto Küsel, a German inmate originally from Sachsenhausen (yet another concentration camp). It was Küsel who gave Kazik an indoor job and inadvertently saved his life. His new job was picking up corpses, putting them on carts, then hauling them to the crematorium for disposal.

He also worked in the warehouse that supplied SS formations. One day, he heard that his friend, a mechanic named Eugeniusz Bendera, was about to be executed. So Kazik hatched a plan.

It had to take place on a Saturday because prisoners only worked till noon, while most of the guards had their weekends off. Unfortunately, that was also the day they locked up the warehouse.

Although it was only supposed to be Kazik and Bendera who escaped, their plan required the use of a heavy metal wagon that needed at least four men to move. So they found two more recruits.

On 20 June 1942, the four men rolled the wagon loaded with garbage out of their barracks toward the waste bins across the street from the warehouse. Even within Auschwitz, different sections were gated off from each other and guards kept a logbook of those who had permission to pass. Kazik’s entire gamble depended on them not checking it.

They didn’t. The Poles were allowed out of their area and toward the bins. As a warehouse and crematorium worker, he knew that there was a hatch that led to an underground tunnel which stored coal and led to the now-locked warehouse. The day before, he had gone into that tunnel to undo the hatch so they could open it.

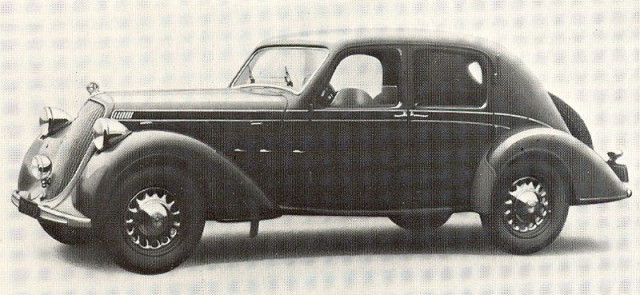

Once in the warehouse, they put on uniforms of the Untersturmführer – a paramilitary rank of the SS. They then crossed the street in full view of passing guards, went to the garage that Bendera worked in, and took the car belonging to Rudolph Höss – First Commandant of Auschwitz.

Bendera drove, while Kazik sat beside him, with the other two in the back. As they approached the main gate, the guard didn’t open it, probably wondering who was driving the commandant’s car. Kazik opened the door and ordered the guard to open it, making sure the man saw his rank insignia.

Terrified, the guard did just that. They later abandoned the car and went their separate ways to minimize their chances of capture. Since the guards had let them out the front gate, forty prisoners weren’t executed. Only Kurt Pachala, the Kapo in charge that day, was.

Kazik went to Ukraine, got fake documents, and worked at a farm. At war’s end, he joined the Home Army, but when the communist government took over, they deemed the Home Army to be illegal. So he was jailed for that, as well.

He served only seven of his ten years, before he traveled to sixty different countries to fulfill his childhood dream far beyond the Vistula River.

For a viewing of Kazik and the Kommander’s Car, click here.

Here is a music video, his granddaughter Katy Carr, made about his escape “Kommander’s Car” Katy Carr.

https://youtu.be/TqvhgS00UdA