In 1945, the final days of World War II were coming to a close – but not before the world was forever changed. Over the years of the war, both those who fought on the battlefields and those who watched from afar were introduced to entirely new evils, surprising successes, and much more.

As the conflict cooled in Germany and the Allied troops ended Adolf Hitler’s Nazi reign, one more enemy remained standing: Japan. The attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941 turned the world’s attention to a new major player in the ongoing war and launched the United States into the middle of the international conflict. Yet that day also led to the creation and dropping of the first-ever atomic bomb, and to the final wartime encounters between the Allied and Axis forces.

After Germany surrendered to the Allied forces and the war in Europe came to a close, Japan remained the sole enemy standing – and Japan was not a nation that would surrender easily. The Allied nations prepared for the costly and deadly possibility of an invasion, readying the plans and the necessary men to fight Japan as had Germany.

All of these plans changed when the world’s first nuclear weapons were introduced and launched. Though the stories of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki bombings are familiar ones in the history of both World War II and the Pacific War, not all went as smoothly as we might think today. In fact, getting that very first nuclear bomb off the ground and to its final destination wasn’t as easy as it sounds in history textbooks.

Getting Project A Off the Ground

Before the world’s first nuclear weapon made its way to Japan, it began under the great secrecy of the Manhattan Project. Though the Manhattan Project started in June of 1941, before the U.S. entered World War II, the bombs that would eventually fall on Hiroshima and Nagasaki weren’t part of the project’s original plan.

Instead, the Manhattan Project was meant to develop fissile, or nuclear, materials; it wasn’t until 1943 that Brigadier General Leslie R. Groves, Jr., leader of the project, spurred the creation of the Los Alamos Laboratory. Groves developed the nuclear lab solely for the purpose of the atomic bomb – he brought Robert Oppenheimer onto the Manhattan Project to lead a new project, Project Y, which would be charged with the design and physical creation of atomic bombs.

The members of Project Y discovered that the aircraft of the time needed significant modifications – and for some, complete redesign – in order to carry nuclear bombs to their drop sites. Furthermore, as test runs took place, only disappointing results were seen; the bombs weren’t falling as intended, and the Project Y team quickly realized that they had a long and thorough road of in-depth testing ahead.

Over the course of the next two years, Project Y developed and executed a careful testing program. By the war’s end in August of 1945, bomb testing had progressed to live explosives – and the completion of the nuclear bomb was growing near. As those involved with Project Y began to see success with the bombs, their spin, and their detonation, it was time to devise exactly how such a history-altering weapon would be delivered to an enemy.

The deployment of the initial nuclear bomb itself fell under Project Alberta, or Project A and the first steps towards this goal took place when the project began in March of 1945. More than 50 people, both U.S. military personnel, and civilians were brought on board for Project A to see its mission to its end goal: to develop the plans that would allow the bomb to be prepared and delivered to its final destination.

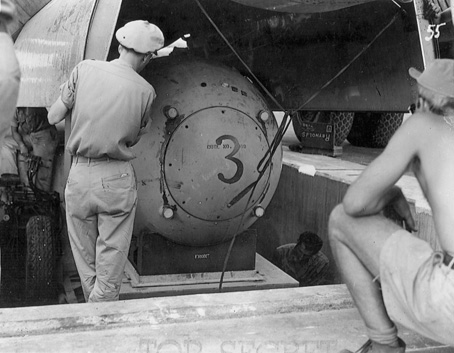

The project was divided into two bomb assembly teams, the Fat Man Assembly Team led by Commander Norris Bradbury and Roger Warner and the Little Boy Assembly Team led by Commander Francis Birch. Unlike the other projects under the larger Manhattan Project, Project Alberta was a team comprised of volunteers – every man who joined this assembly and delivery project volunteered for his position.

Together, the Army, Navy, and civilian participants worked on Tinian, the Pacific Ocean island that was already the site of so many nuclear bomb tests.

The Test Runs Begin – Yet with No Actual Plan for The Bombs

Once Project A began, the focus shifted from perfecting the bombs themselves to readying them for attack as soon as possible. There was just one minor concern: the Project A team didn’t have any attack orders. Instead, they were simply charged with readying the first Little Boy by August 1st, 1945, and preparing the first Fat Man next, unsure whether or not the bombs would actually be dropped at any time in the near future.

While the men of Project A worked to prepare these bombs, elsewhere the U.S. military was already conducting test combat missions. From July 20th to July 29th, twelve combat missions flew over targets in Japan, each aircraft carrying highly explosive Pumpkin bombs. Two of the men connected to Project Alberta, Sheldon Dike, and Milo Bolstead, flew aircraft during these missions, but no one knew that they were in any way connected to Little Boy, Fat Man, or the means of assembling and dropping either of these bombs.

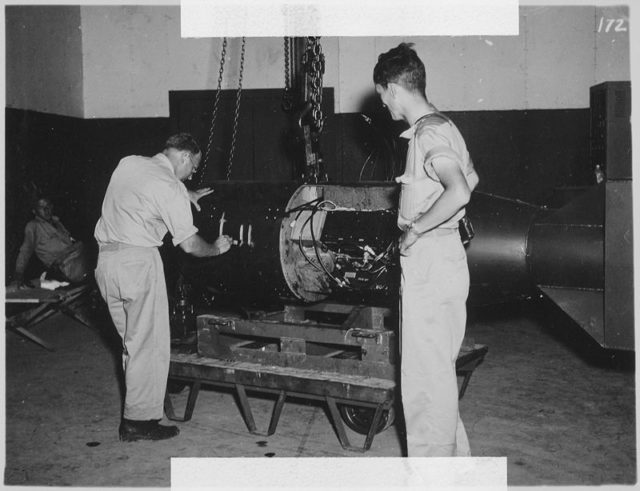

So, tests of Little Boy continued throughout the summer months of 1945. The bomb itself was already known to be powerful and effective thanks to other projects within the larger Manhattan Project – now, the volunteers of Project Alberta needed to figure out the most effective way to assemble the bomb.

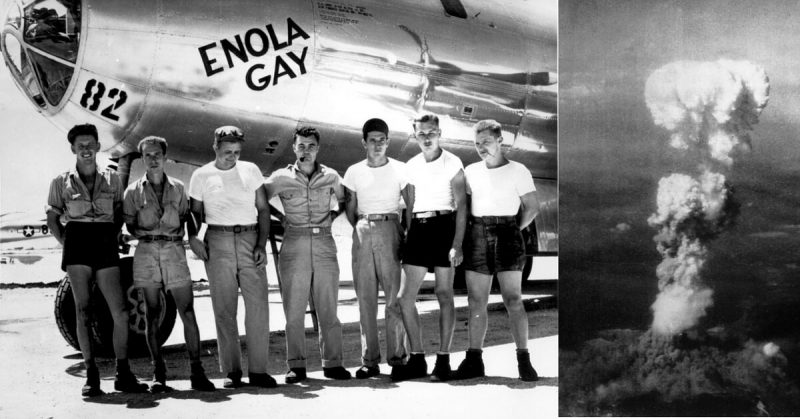

As the team properly assembled different Little Boy models, the bombs were immediately used for test drops. The first use of a nuclear weapon against an enemy was drawing nearer. On July 31st, Enola Gay, the plane that would soon carry out the bombing of Hiroshima, ran through a dress rehearsal with one of the prepared Little Boys.

Even more test runs were conducted, and it was finally decided that the Little Boy was ready – the eleventh bomb assembled by Project A was the winning design, chosen to be the build used in real time.

After Enola Gay ran its dress rehearsal on July 31st, it was time for all of the practice and preparation to pay off. While the test runs were taking place throughout July, the order to unleash one of the nuclear bombs was on its way to the men working with Project A. On July 25th, General Carl Spaatz received an order to attack four Japanese targets in the first days of August.

The order, signed by General Thomas T. Handy in the role of acting Chief of Staff of the U.S. Army, set in motion the preparation of nuclear bombs for Hiroshima, Kokura, Niigata, and Nagasaki – and Handy was to have his men carry out the order as soon as possible.

Little Boy Proves Problematic

Armed with their new order from Hardy, the Project Alberta team and many others from the Manhattan Project got to work – it was time to put their practice to action. However, as the men began readying both Little Boy and Fat Man bombs for the four anticipated drops, problems quickly arose.

Three different sets of explosives intended for Fat Man assemblies were discovered to be badly cracked, which left teams unable to use those crucial pieces in any bombs. The problems grew even worse when the aircraft began their test runs. In order to successfully launch an attack on any one of the Japanese targets, the plan required either a Fat Man or Little Boy to be loaded onto a B-29 plane fully assembled. Once the bomb and the crew were on board, the B-29 would take off towards its target.

In the week leading up to the attack on Hiroshima, the B-29s brought only bad news. Four separate B-29s crashed and burned on the Tinian runway – and if such an event happened while a B-29 was carrying a nuclear bomb, the results would be disastrous. Should the crash spark a fire, the flames would burn the bomb’s explosive material and cause it to detonate.

Military leaders were unsure what to do: should they evacuate the troops stationed on Tinian in case a crash did happen? Or was there another way to safely get the bombs off the island and into the air? It was decided that the solution would be a new bomb assembly plan. Instead of building the Little Boy meant for Hiroshima on the ground, the bomb would be loaded onto the plane unarmed – its explosives would be packaged separately, and the aircrew would need to arm the bomb en route to its final destination.

With a new twist on the bomb-building plans created by Project A, the first Little Boy was prepared to make its way to the first of the intended Japanese targets. In the early hours of August 6th, 1945, the Enola Gay crew loaded their aircraft with the unarmed Little Boy and took to the air. Eight minutes into the flight, the crew began assembling the final parts of the bomb, arming and readying it for detonation in under half an hour.

Despite the problems that occurred before takeoff and during the test runs, the Enola Gay successfully completed its mission – at 9:12 GMT, the bombing run began, and the drop took place within three minutes. 45.5 seconds after the bomb fell from the aircraft, the Little Boy detonated over Hiroshima.

Although the morality of this event, the first use of nuclear weapons witnessed by the world, is still hotly debated even today, the story of how that Little Boy came to be is not a simple one. With no firm orders, no deadline, and many surprises up until the very last days before the drop, that first nuclear bomb was no easy feat. Little Boy’s legacy may be one of deadly damage, but it nearly exploded on takeoff even before it set out on its path to Hiroshima.