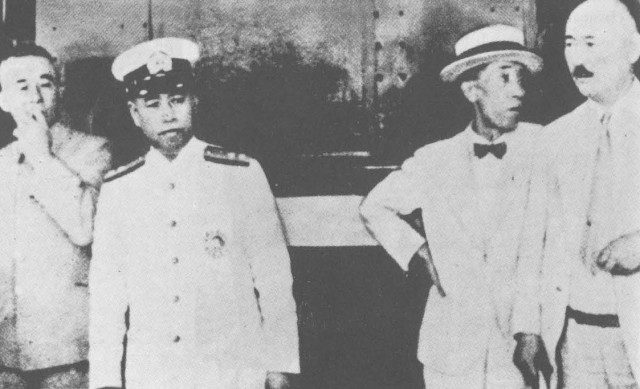

The man who planned the attack on Pearl Harbor, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, was an unusual and contradictory figure. A man with peaceful international connections around the world, he would lead his country’s navy in a war he did not believe in, trying to win a conflict he expected to lose. Though a senior figure who was not fighting on the front line, he would die in military action, as the tide of war hung in the balance.

1. An International Figure

Born in 1884, Isoroku Yamamoto became a career naval officer. He graduated from the Imperial Japanese Naval Academy at the age of twenty, was wounded at the Battle of Tsushima in the Russo-Japanese War, returned to training at the Naval Staff College, and emerged as a Lieutenant Commander in 1916.

The Japanese naval establishment was less aggressive than that of the army, and Yamamoto was an advocate of gunboat diplomacy over actual war.

This was particularly true in relation to the United States, a country he knew well. He studied at Harvard from 1919 to 1921, was twice the naval attaché to Washington, and while in the US took the time to study its business practices and customs. He accompanied diplomats to naval conferences in 1930 and 1934, providing military insight into talks about arms limitation.

2. Naval Innovations

Initially a gunnery specialist, in 1924 Yamamoto changed his focus to naval aviation. Aerial combat had only been a feature of warfare for a decade, since the First World War had pushed the European powers into finding ways to fight with aircraft. Yamamoto was therefore at the cutting edge of military thinking, dealing with techniques and technologies that would be vital to the very different naval combat of World War Two.

First as head of the Aeronautics Department and then as commander of the First Carrier Division, Yamamoto gained extensive experience in his field. He pushed for innovations in naval aeronautics, such as a focus on long-range bombers operating from land against enemy fleets. This led to the adoption of land-based bombers equipped with torpedoes, and long-range aircraft such as the Mitsubishi G3M and G4M medium bombers, which could fly great distances but at the price of fragile, vulnerable frames.

Made into an admiral and commander in chief of the navy, Yamamoto brought innovative approaches to the way existing forces were fielded. Gathering Japan’s six largest aircraft carriers into the single First Air Fleet, he provided the Japanese navy with a force of incredible striking capacity. The downside of this was that it put all Japan’s best eggs in one basket, making her best carriers vulnerable to being taken out in a single successful attack.

3. Opposition to War

As Yamamoto made his changes, Japan was heading towards war. The army was generally more belligerent than the navy, and Yamamoto fitted this picture, opposing the army’s grandiose plans not only to conquer East Asia, but to take on the United States of America.

Yamamoto’s opposition was not based on principles. For all that he admired things about the US, he was a military man and a loyal supporter of Japanese power. He opposed the war because he did not believe Japan could win it. He believed that America was too vast and powerful for Japan to conquer and that without conquering them Japan would not be able to defeat the Americans.

By the time he was proven right, Yamamoto would be dead and his country ruined.

4. The Reluctant Planner

“If I am told to fight regardless of the consequences, I shall run wild for the first six months or a year, but I have absolutely no confidence about the second and third years.”

– Admiral Yamamoto

Unfortunately for all involved, the pro-war faction gained control of the Japanese government. They were determined to break American influence in the region and dominate it themselves. They believed that through a fast offensive they could seize the oilfields and the other raw resources they needed to support the war, and so emerge victorious beyond that first year.

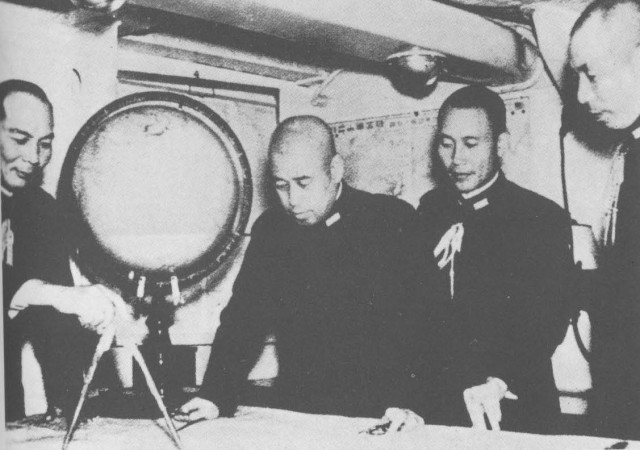

Though he still expected disaster, as a loyal officer Yamamoto bowed to the will of his superiors. He was now faced with the unenviable task of planning the initial knockout blow meant to win that first stage of the war. And so he worked to the best of his ability in planning the attack on the American naval base at Pearl Harbor. This surprise attack with aircraft and midget submarines was meant to destroy the American carrier fleet, crippling Japan’s opponent before the war really began.

The attack on 7 December 1941 was only a partial success. The American fleet suffered great damage but was far from taken out. The Americans were enraged by the attack and launched themselves into the war with total commitment and with great determination.

5. After Pearl Harbor

Initial Japanese successes at sea did not lead to American negotiating an end to the war, as Yamamoto and others had optimistically hoped. As the Japanese high command grappled over the decision of what to do next, Yamamoto went back and forth in backing others, until he was able to gain support for his own plan to advance on Midway.

The resulting Battle of Midway was a significant defeat for the Japanese and a turning point in the war.

6. Death in Action

Following Midway, the Japanese lost the momentum of their initial successes. Yamamoto kept them pushing against the Allies, and Japanese resources, in particular the supply of planes on which his plans were so reliant, started to become scarce. In the longer war of attrition, American industry showed its strength.

In April 1943, following a further significant defeat at Guadalcanal, Yamamoto undertook an inspection tour in the south Pacific to help raise morale among forces there. The Americans got word of his location and, on direct orders from President Roosevelt, ambushed Yamamoto’s transport plane on 18 April. Yamamoto and those traveling with him were killed.

He died in a war he opposed, still trying to win it to the end.