Few 20th-century generals have earned such legendary status as Erwin Rommel. The Desert Fox was one of the most famous German commanders of WWII, second only to Hitler himself.

Who was Rommel and what did he do to earn such fame?

First World War

Rommel served as an infantry and artillery officer in WWI. A bold leader, his most notable achievement came in October 1917 on the Italian front.

As part of an attack in the Isonzo Valley, Rommel led a detachment across the western mountains. Advancing from peak to peak, he defeated forces far outnumbering his own. In two and a half days, his detachment lost six men dead and 30 wounded. In return, they captured thousands of Italian soldiers, 80 artillery pieces, and a series of tactically significant heights. For his actions, Rommel was awarded the Pour le Mérite, Germany’s highest award for courage.

Due to Rommel, the Isonzo advance was a success although his superiors failed to make the most of it. Afterward, he was posted away from the fighting, gaining command staff experience.

Between the Wars

Following WWI, there were fewer opportunities for advancement in the defeated and diminished German Army. Rommel continued to serve, spending eleven years as a company commander in the 13th Infantry Regiment.

In 1929, he became an instructor at the Infantry School in Dresden. While there, he wrote a book called Infantry Tactics, describing his frontline experiences and the conclusions he had drawn from them. The book was a bestseller and got the attention of Adolf Hitler, the leader of the rising Nazi Party.

Over the following years, Rommel shifted between posts as an instructor and as a commander. Meanwhile, Hitler gained control of the country. In 1938, Rommel was seconded to command the Führer’s personal security unit.

He accompanied Hitler through the Munich crisis of 1938 and the invasion of Poland in 1939. Hitler liked Rommel because he was bold, brave, and unlike many German officers he did not come from an aristocratic family.

Following the invasion of Poland, Hitler asked Rommel what he would like to command next. Rommel requested a panzer division.

The Low Countries and France

Rommel’s first experience commanding tanks in the field came in May 1940, with the German invasion of France through the Low Countries.

Rommel advanced with incredible speed, allowing his troops to become stretched to seize objectives swiftly. He raced ahead of other divisions, built a bridge across the Ourthe River, and was crossing it by dawn on the second day. The Allies believed they could hold the River Maas for a week. On May 13, Rommel forced a crossing in a single day.

Rommel’s willingness to lead from the front was an inspiration. He joined his engineers wading in a river under gunfire to build a bridge.

Having created a bridgehead across the Maas, Rommel split his division in two. Leading one column, he rushed across France. His sudden appearance miles behind the enemy lines earned his troops the nickname “Ghost Division.”

On the Maginot line, Rommel launched a cunning night attack, using artillery barrages, armored vehicles, and assault pioneers to smash through fortifications.

Around Arras, Rommel met the British Expeditionary Force and was almost captured when his escort group was cut off. His forces were the spearhead of the advance on Dunkirk. Then they swept south, driving 240 kilometers in one day, to capture the naval base at Cherbourg.

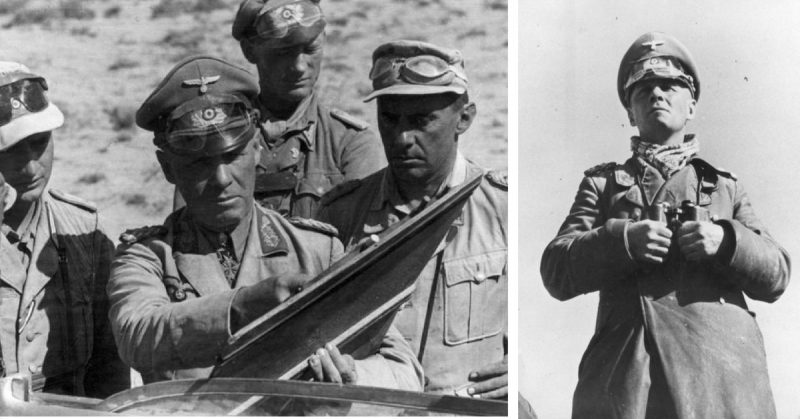

Africa

From France, Rommel transferred to North Africa. There, the failures of the Italian Army had left the British with the upper hand. The Germans stepped in to prevent the Axis powers being humiliated and to control supply routes through the Suez Canal and Mediterranean.

The North African deserts were where Rommel reached the height of his fame. In the spring of 1941 through bold flanking maneuvers, careful use of intelligence, and a strong grasp of the potential of tanks, he drove the Allies back east. However, German resources were then diverted to the Russian front. The British, under Montgomery, then turned the same tools of maneuver and intelligence against Rommel.

The war in the desert shifted back and forth until the arrival of Anglo-American forces further west in Operation Torch. Rommel found himself trapped between two armies, at risk of being crushed.

Only then, as a desperate last measure were the troops sent that could have won him the campaign earlier in the war. It was too late. He withdrew into Tunisia, from where the German forces were extracted.

Rommel had become a legend in Africa. He had earned the nickname of the Desert Fox. He became such a terror to the British that their officers had to spread propaganda among their men deflating his legend.

The Last Campaign

After Africa, Rommel helped to defend Italy. Then late in 1943, he was moved to northwest Europe, in expectation of an Allied invasion. He helped prepare for the defense of Normandy but was on leave in Germany when the D-Day landings occurred on June 6, 1944. Rommel raced back to France to take control. He believed the best chance of victory was to seal off and destroy the beachheads, but Allied air power made it impossible.

As he fought to hold up the Allies, he clashed with Hitler, who openly criticized Rommel’s handling of the defense of Normandy and refused him permission to fight the war his way. Rommel wanted a tactical retreat, whereas Hitler wanted him to stand to the last man.

On July 17, Rommel’s car was attacked by a fighter-bomber and crashed. He was hospitalized.

Three days later, an assassination attempt by senior Germans failed to kill Hitler. Under interrogation, they implicated Rommel in the plot. He was given a choice – a public trial and persecution of his family or a suicide disguised as a heart attack. He chose suicide and was given a state funeral, still treated as the hero most Germans believed him to be.

Source:

James Lucas (1996), Hitler’s Enforcers