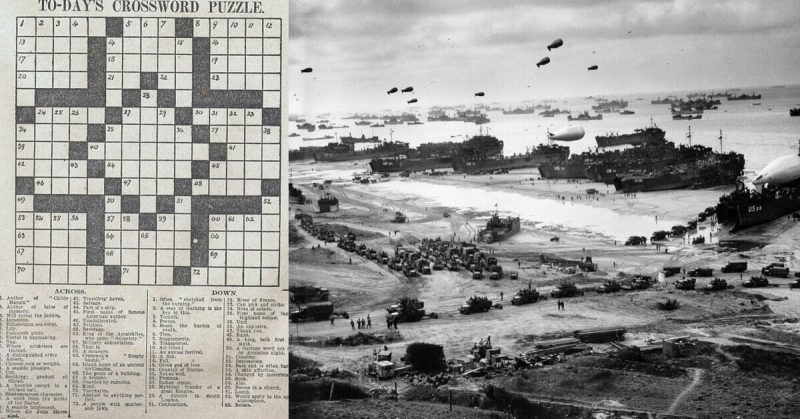

To end WWII in Europe, the Allies planned a massive assault on Normandy, France, in 1944. Over 5,000 ships, 1,200 planes, and almost 160,000 men were poised to invade Europe from the British Isles, when something almost put a stop to it – a series of crossword puzzles.

It all started with the Dieppe Raid on August 19th, 1942. Dieppe is also in Normandy but further North, which was where over 6,000 Allied troops, mostly from Canada, attacked at 5 AM.

They had four main goals: (1) to prove that it was possible to capture a slice of Nazi-occupied Europe, (2) to boost Allied morale, (3) to gain intelligence, and (4) to destroy coastal defenses and other sensitive installations.

They failed. By 3 PM, almost 60% of the invaders had been killed, captured, or were fleeing back to Britain. So, of course, the Allies wanted to know why.

The likeliest explanation was that the Germans had been warned of the attack. But how? Suspicion fell on The Daily Telegraph, a British paper still in business today. It wasn’t that the broadsheet gave advanced notice of the invasion… at least not openly.

But they did (and still do) have a crossword puzzle section, and that’s where suspicion fell. Because two days before the Dieppe invasion, the clue, “French port” was given. And the solution was “Dieppe,” given the following day – the day before the invasion.

Coincidence? Military Intelligence, Section 5 (MI5) didn’t think so, so they looked into it. It turned out that the man responsible for the crossword section was Leonard Sydney Dawe – the headmaster of Strand School.

Given that Dawe was a veteran of WWI and that nothing linked him to Nazi Germany, MI5 concluded that it was just that – a chilling coincidence.

The Strand School for boys in south London no longer exists, but when the Germans began their bombardment of the city in 1939, Strand was moved to Effingham in Surrey – close to where many American and Canadian forces were based.

Believing that the war was turning in the Allies’ favor, the Third Washington Conference (also called the Trident Conference) was held in Washington, DC in May 1943. It was there that plans for an Allied invasion of Sicily, France, and the Pacific were discussed.

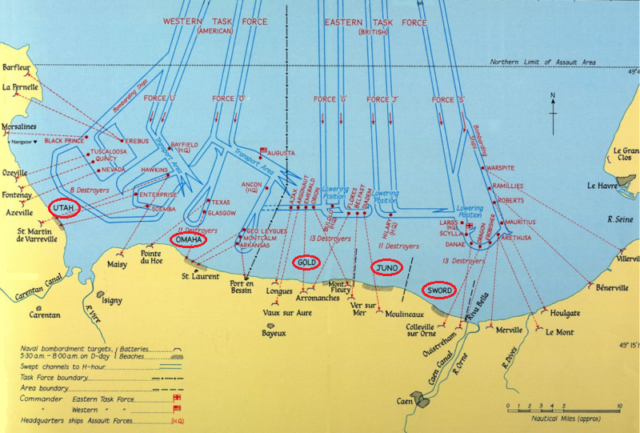

The French invasion was called Operation Overlord. It was to take place on June 5th, 1944 and involve a series of joint sea and air landings along the Normandy coast. Rather than mass themselves at one spot, however, they were to land at five different areas according to nationality.

The Americans were to land at two places. The first was on the left bank of the Douve estuary – codenamed Utah Beach. The second was the stretch which included Sainte-Honorine-des-Pertes, Saint-Laurent-sur-Mer, and Vierville-sur-Mer – referred to as Omaha.

The British were also given two landing sites – the first along Saint-Aubin-sur-Mer to Ouistreham (Sword Beach), as well as the strip from Arromanches-Les-Bains, Le Hamel, and La Rivière (Gold Beach). As for the Canadians, they were assigned the stretch from Courseulles, Saint-Aubin, and Bernières (Juno Beach).

To ensure the quick off-loading of cargo, portable bridges called “Mulberry Harbors” were built. Ships would tow these to France, assemble them at sea, then drive equipment onto the beaches.

Since the invasion was massive, there was no way to keep it a total secret from the Germans. The solution, therefore, was to keep them guessing as to exactly when and where the invasion would take place.

So the Allies launched Operation Bodyguard. This was a series of diversions which convinced the Germans that Normandy was simply a distraction, while the main invasion was to take place elsewhere.

Although the Germans bought it, they didn’t want to take any chances. As a result, they stretched their forces thin in a desperate attempt to cover all of their bases. To keep them at it, absolute secrecy was vital.

Then, in February 1944, one of The Daily Telegraph’s crossword answers was “JUNO.” The following month, it was “GOLD,” and the month after that, it was “SWORD.” Coincidence? MI5 thought so.

But when the next puzzle included the clue, “One of the US,” they began to wonder. The next day, the answer given was “UTAH.” Now they started to worry.

As soon as the May 22nd edition came out, MI5 anxiously grabbed a copy. Scanning the crossword section, they found yet another suspicious clue – “Red Indian on the Missouri River.” And what was the answer given the next day? “OMAHA.” So now they were thinking, “Hmm…”

It got worse. The May 27th edition had another damning clue – “Big-Wig.” And the answer was? “OVERLORD.” The clincher came on June 1 – four days before lift-off. The solution to 15 Down was “NEPTUNE.”

The MI5 hadn’t bothered talking to Dawe about the Dieppe incident, but now they had no choice. They arrested him at his school to the astonishment of the students and staff, before bundling him into a car. They then banned the paper’s next publication in case “DDAY” appeared in the next crossword.

![The U.S. Coast Guard manned USS LST-21 unloads British Army tanks and trucks onto a "Rhino" barge during the early hours of the invasion on Gold Beach [1], 6 June 1944. Note the nickname "Virgin" on the "Sherman" tank at left.](https://www.warhistoryonline.com/wp-content/uploads/sites/64/2016/08/1024px-US_Navy_LST_Landing_Sherman-640x438.jpg)

So was it all just a coincidence? For many years, everyone thought so… at least till 1984 when Ronald French (a former student at Strand) came forward.

Dawe didn’t create crossword puzzles, apparently. He instead had students arrange words on a grid, and when he was satisfied, provided clues to solve them by. Then he’d send the finished work to the paper, taking credit for the work.

According to French and other former students who later came forward, everyone in Surrey knew the code words. How? Because they all hung around the Americans and Canadians.

French didn’t know what the words meant, only that the servicemen often said them. So when told to work on the crossword puzzles, he included the codes. After his release, Dawes confronted French and accused him of putting the entire country at risk.

Despite their own secrecy, the MI5 had apparently forgotten to tell the army to keep their mouths shut.