During WWII the Japanese Navy changed its communication codes on a regular basis, this was a mammoth task as new codebooks had to be transferred to all ships, islands and outposts.

Submarines were the logical choice for this task as they could reach their destination stealthily and could fight back when attacked. One of these subs was the I-1, unfortunately for the Japanese, she had an encounter with the New Zealand Navy.

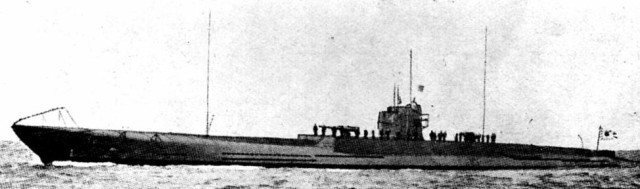

The Japanese submarine I-1 measuring 320’x30’, she was captained by Lieutenant Commander Eiichi Sakamoto. With her twin shaft MAN 10 cylinder stroke diesel engines and two electric motors, she could travel 18 knots on the surface (20.71 mph) and eight knots (9.20 mph) below surface.

The I-1 was armed with a 14 cm/40 naval gun at the front and a 46 Daihatsu barge in the back, as well as six 533 mm torpedo tubes and 20 type 95 oxygen-driven torpedoes.

On 24 January 1943, she left her base at Rabaul, Papua New Guinea for the island of Buin with 20,000 codebooks and supplies. On January 29, she was heading for Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands when she was discovered by two New Zealand naval trawlers – the HMNZS Kiwi (T102) and the HMNZS Moa (T233).

Both measured 168’X157.5’ and could travel at 13 knots (14.96 mph). Each were armed with a 4” gun, a 20 mm Lewis machine gun, mine-sweeping equipment, and an ASDIC (the precursor of sonar).

The Kiwi didn’t start off well. She left Britain in 1941 with the Moa and the Tui, but a storm hit and she suffered damage, forcing her to dock in Boston, Massachusetts for repairs. While the Moa waited, her captain, Lt. Cdr. Peter Phipps, convinced the US Navy to install a 20 mm Oerlikon in exchange for two bottles of gin.

The Kiwi and the Moa joined the 25th Minesweeping Flotilla in the Solomon Islands under US Navy Admiral William F. “Bull” Halsey, Commander of the US Pacific Fleet. In mid-January 1943, the Kiwi found the remains of a US Navy ship so its captain, Lt. Cdr. Gordon Brisdon, asked permission to salvage some of its parts, including its Oerlikon. The Americans were only too happy to help them install the cannon, which came in handy a few days later.

On January 29, the Kiwi and the Moa were a mile apart doing a routine sweep off Kamimbo Bay (on the northwestern end of Guadalcanal) when they entered history. The I-1 had done a cursory sweep of the surface with its periscope, but failed to see the two ships, so it surfaced at 6:30 PM… directly in front of the Kiwi.

The submarine dived, but the moon was in the last quarter and the tropical waters were phosphorescent. With her dark hull, the I-1 stood out. The Kiwi’s ASDIC located the submarine, so Brisdon ordered six depth charges dropped.

One hit close to the I-1’s stern. The resulting shockwave knocked out the port, electric motor, flooding her rear storeroom and popping some hull rivets. The lights went out as the submarine sank to the bottom over 180 meters below (100 meters lower than what she was built for). Upon impact, her two forward torpedo rooms crumpled and became unusable.

Back on the surface, the Kiwi’s ASDIC lost the I-1, but the Moa found it, allowing the Kiwi to drop six more charges. Desperate, Sakamoto ordered the submarine to the surface. With her electric motor out, the I-1 could only make 11 knots (12.65 mph) with her starboard diesel engine, but they were close to Japanese-occupied territory so they thought they had a chance.

Brisdon wanted to ram the submarine, but the I-1 was double the size of the Kiwi, so the crew members were reluctant.

“A weekend leave for everyone if we ram that thing!” Brisdon yelled.

The Kiwi hit the I-1 on the port-side behind the conning tower. Japanese submariners immediately began to leave their vessel; some fell in the water while others dived as the Kiwi backed up and fired its Oerlikon. The submarine’s hull was too thick, but it had some barges hooked to its afterdeck, so those burst into flames. The Japanese gun crew was quickly taken care off, but more took their place until, their commander Sakamoto was killed.

The Moa also fired and shot parachute flares into the air to illuminate the battle, but couldn’t get too close. Aboard the Kiwi, 23-year-old Signalman Campbell Howard Buchanan manned the searchlight and 10-inch signal lamp, making him a target for Japanese return fire.

“Hit her again!” Brisdon roared, promising a week’s leave – but the I-1 still wouldn’t sink.

Return fire from the deck of the submarine hit the Kiwi, and Brisdon promised a two-week leave in Auckland if they rammed her a third time. They rammed again and they ended all the way on I-1’s deck before sliding back off. For a moment all was calm.

With the captain dead, Torpedo Officer Lt. Koreeda Sadayoshi took command. Four Arisaka Type 38 rifles were passed among the best sharpshooters of the surviving crew. As the Kiwi’s fore slid off the I-1’s deck and back into the water, one hit Buchanan, but he kept manning the lights.

So Sadayoshi ordered all the officers to get their swords and try to board the Kiwi. The navigator, Lt. Sakai Toshimi, was a Kendo 3rd dan swordsman. As the Kiwi made its fourth approach, he grabbed the railing… but the impact was too hard, and he lost his grip.

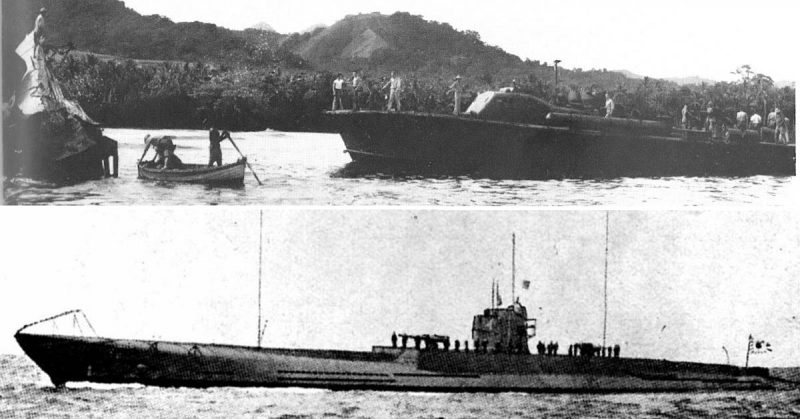

The I-1 was taking on water and its stern was sinking. By 8:30 PM, it was all over. Sadayoshi ordered the I-1 to run aground on Guadalcanal, where it rested at a 45° angle. With 27 dead, missing, or taken as POWs, 66 reached the shore and made it back to their base. Buchanan was the only casualty on the New Zealand side.

The sinking of the Japanese submarine was only one of the contributions made by New Zealand to the defeat of Japan in the Pacific. The sinking of I-1 remains one of the proudest moments in New Zealand naval history.

Critical codes remained on board and the Japanese command tried unsuccessfully to destroy the boat with air and submarine attacks. The US Navy reportedly salvaged code books, charts, manuals, the ship’s log and other secret documents.