Military intelligence was vital to the Second World War. Trickery abounded, as commanders tried to deceive opponents about their plans.

Tricking Rommel at Alamein

Intelligence and counter-intelligence played a major role in the North African campaign. As early as 1940, the British used agents to make the Germans believe attacks were coming at times and places when they were not. It proved very useful in distracting the Germans and exposing their weaknesses, for example when they began to run short of fuel.

The most extensive instance of this came during the fighting at Alamein in October to November 1942. The Germans had already been tricked into believing in fictional troops and misdirected about where British forces were located. This misinformation work relied on radio signals and agents, but it could be undermined if aerial reconnaissance did not match.

The British built a water pipeline heading south through the desert. It’s direction of travel and the time taken to erect it indicated they would be supplying a major assault in that area, which would launch in the middle of November.

Meanwhile, the real preparations were underway further north. Troops and vehicles were disguised to hide them from aerial reconnaissance. When the British attacked in the north, it sent the German forces under Rommel reeling. They had been preparing in the south.

Operation Mincemeat

The most famous deception of the war, Operation Mincemeat was one small but significant part of a wider web of deception.

Following their success in North Africa, the Allies were preparing to invade Italy, starting with Sicily. The problem was that it was such an obvious target. The Germans and Italians were bound to put up stiff resistance.

To counter this, the Allies began a campaign of false information similar to that used in Africa. It led the Germans to believe they had intercepted vital intelligence and uncovered what the Allies did not want them to; that the invasion was coming further east.

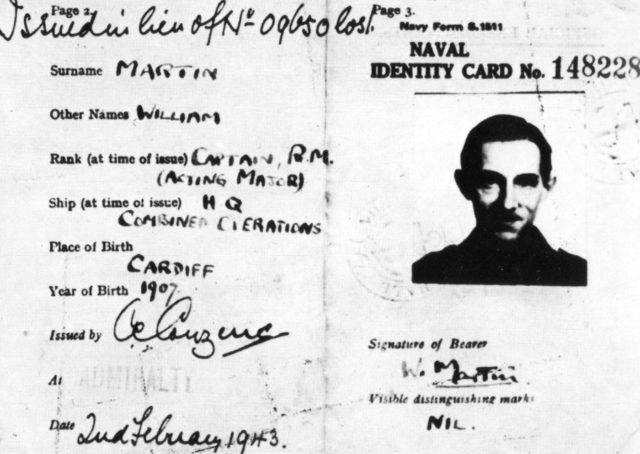

Then the ingenious Operation Mincemeat was used. The body of a dead civilian was dressed up as an officer, complete with a false identity and paperwork. Plans for a supposed Allied invasion were placed on his body. It was then dropped off at sea in a place where it would be picked up by locals sympathetic to the Axis forces.

Apparently stumbling across the false plans by accident, the Germans and Italians were completely duped. Forces were diverted away from the real invasion zone. The ground had been laid for a safer invasion of Sicily.

FUSAG

As they prepared to invade Normandy, the Allies faced the so-called Atlantic Wall, a string of substantial defensive positions along the coast. With 12,000 fortifications and 6.5 million mines, it was a formidable target. The best way to weaken the enemy position was to trick Hitler into thinking they were attacking elsewhere.

The obvious place was the Straits of Dover, the narrowest point in the English Channel. It was a plan that made perfect sense, as it would be the shortest crossing and allow air and artillery support from southeast England. It made so much sense that it would be easy for Hitler to believe.

The Allies created an imaginary army – the First United States Army Group (FUSAG). Led by General Omar Bradley, it was supposedly based in Kent and had a headquarters housing Bradley and his staff.

Film studios and theaters provided set builders who were brought to Kent to create a mock army. They built barracks and tents, fake tanks and landing craft, all convincing enough to trick German aerial reconnaissance. The airwaves of Kent were flooded with radio traffic from non-existent units.

As the invasion date approached, General George S. Patton was put in charge. Patton had been suspended from real command for slapping exhausted soldiers. This posting meant he was still useful, as the Germans feared his aggressive and effective leadership.

To add to the charade, an injured German officer on his way home was shown a massive armed force gathered in Kent, including Patton. He supplied eyewitness testimony to his superiors that the army was real. In reality, he had been shown soldiers in a different part of the country.

It worked. Hitler focused on defending the Pas de Calais, not the invasion beaches. Weeks after D-Day, he was still holding forces back ready to face FUSAG.

Operation Titanic

On the night Allied forces set out for Normandy, a new deception was underway.

Much like FUSAG, Operation Titanic was about tricking the Germans into reducing their defenses in vital areas. Titanic’s target was the area around Omaha beach, where the most difficult and bloody landings took place.

Late in the evening of June 5, 1944, forty transport planes took off from southern England. On board were ten soldiers of the Special Air Service (SAS), Britain’s elite Parachute Regiment. Accompanying them were 500 “Ruperts” – crude dummies made of sand, straw and fabric, each one with a parachute.

Just after midnight both the Ruperts and the paratroopers were dropped over the French countryside, away from the landing beaches. The dummies contained incendiary devices so they would catch fire on landing, removing evidence they had not been real paratroopers starting an attack. The real soldiers had fireworks and gramophone recordings of gunfire with which to fake battle noises.

At around 3 AM, the Germans responded to reports of an attack. Thousands of soldiers were diverted away from the area around Omaha beach to deal with the ten SAS men and their hundreds of straw comrades.

Those SAS men were the first to land on D-Day. Only two of them made it home alive, but thanks to them hundreds of American lives were saved on Omaha beach.

Sources:

Ralph Bennett (1999), Behind the Battle: Intelligence in the War with Germany 1939-1945.

Gordon Brown (2008), Wartime Courage.

Nigel Cawthorne (2004), Turning the Tide: Decisive Battles of the Second World War.