Just like the war on land, the naval sphere of the First World War was dominated by industrial methods and new fighting machines.

The Arms Race

The war was preceded by a dramatic decade-long naval arms race.

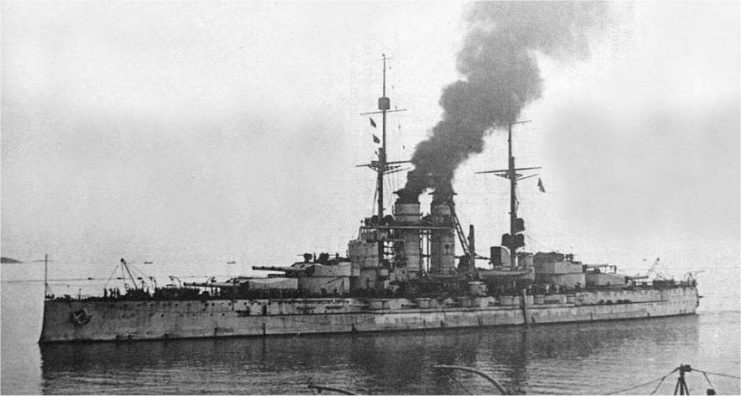

The race began in earnest when the British built the warship HMS Dreadnought. Launched in 1906, the Dreadnought was a dramatic leap forward in battleship design. For the first time, its main armament was made up entirely of the largest available guns.

The combination of an improved range and greater firing control gave it huge destructive potential. Despite being larger than any of its predecessors, it was also faster than most thanks to its steam turbines, which were being used on a battleship for the first time.

The British built more ships like the Dreadnought, and other nations followed suit trying not to be left behind. By 1914, all the major powers had ships in a class named after its originator – the dreadnoughts.

Other innovations were also taking place. Battlecruisers were built to provide lighter, faster ships still while still able to carry heavy weaponry. Torpedo boats were a cheap way of defending coastal waters and harassing enemy shipping. And under the surface, submarines were preparing to fight.

Commerce Raiders

The first naval actions of the war were relatively small-scale engagements. The British were reliant on seaborne trade to feed their population and their industry. The Germans, therefore, sent out raiding ships to harass Britain’s maritime trade routes.

The most cunning of these were the auxiliary commerce raiders, civilian ships carrying disguised weapons. They were meant to lure enemy ships in by looking vulnerable and innocent, then attack them. The most successful, the Möwe, sank 34 merchant ships.

Armed merchant cruisers were civilian ships, usually fast passenger liners, equipped with guns. The British and French also used these, but like the Germans, they found them too vulnerable to last long.

The heaviest ships engaged in commerce raiding were eight German light cruisers. They began the war by attacking Allied shipping in the Atlantic, Caribbean, Pacific, and Indian Ocean. The Emden sank British merchants and French and Russian battleships before being sunk herself by the Australians. Others were less successful and were quickly hunted down. But it was a group of these raiders that triggered the first significant naval battles of the war.

Coronel and the Falklands

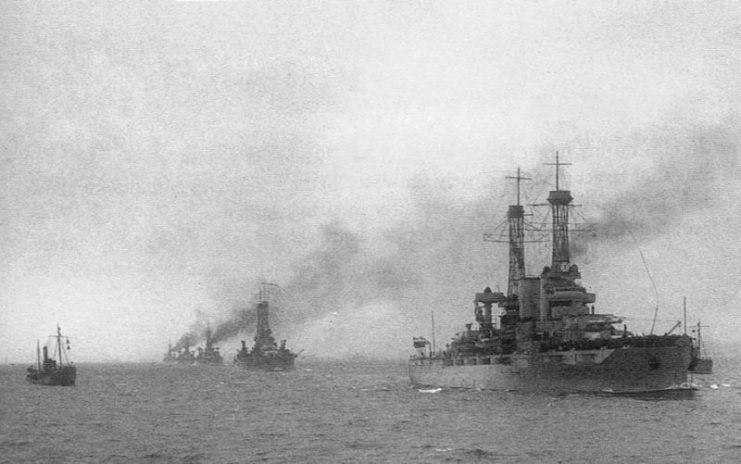

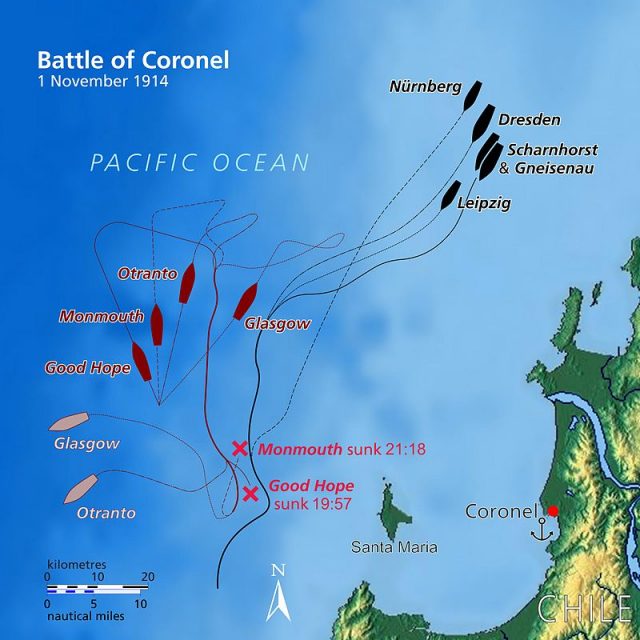

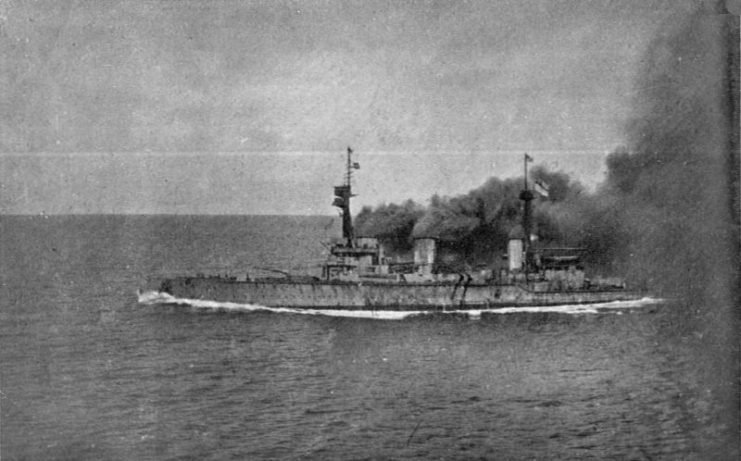

On the 1st of November 1914, a British squadron engaged a group of German raiding cruisers near the port of Coronel in Chile. The weaker British were defeated in only 40 minutes, losing two armored cruisers, while the Germans emerged victorious without loss.

From Coronel, the Germans sailed around Cape Horn and into the Atlantic. There they approached the British outpost at the Falkland Islands.

Unknown to the Germans, the British had sent a strong task force to hunt them down – a force now based at Port Stanley in the Falklands. The British emerged and attacked the Germans, who tried to escape. Four of the five German cruisers were sunk, giving the British vengeance for their losses at Coronel.

Jutland

For the next year, the British and Germans eyed each other warily across the North Sea, each looking for a chance to engage the other on their own terms. At last, in May 1916, the Germans made their move. But the British knew that they were coming. From the 31st of May to the 1st of June, they fought the Germans at Jutland, the only major fleet action of the war.

The battle began badly for the British, as their battlecruiser squadron took a pounding from the German fleet. However, the tables were turned as the Germans pursued the battlecruisers north, straight into the guns of the main British fleet.

As the British dreadnoughts opened fire from a tactically advantageous position, the Germans suffered heavy damage and began to retreat. The British pursued them through the night but failed to trap them, and the German fleet eventually escaped to their home port.

The British lost 14 warships while sinking 11 German ships. Twice as many British crewmen lost their lives during the engagement, yet Jutland was a success for the British as they forced the German navy back to port. The German fleet remained there for the rest of the war, giving the Allies domination of the North Sea and beyond.

The Mediterranean

The Mediterranean was a backwater of the war, with no great confrontations taking place on the sea. Anglo-French forces launched an ineffective naval bombardment of the Dardanelles before the Gallipoli campaign, and there was some fighting between smaller ships. The Italian navy’s torpedo boats were among the most successful combatants, sinking a battleship and a dreadnought late in the war.

Critically for the Allies, the Austro-Hungarian and Turkish navies were contained, preventing them from interfering in the wider war.

The War Beneath the Waves

A new form of weapon led to a new dynamic in naval warfare – submarine raiding.

The Germans committed most heavily to submarines with over 350 of their U-boats serving over the course of the war. The Allies fielded much smaller submarine fleets. The Allies also made the mistake of trying for variety in their submarine designs, while a focus on consistency let the Germans build and crew theirs more quickly and easily.

Increasingly limited in what they could do on the surface, the Germans used submarines to attack Allied supply lines. The Allies responded by developing better anti-submarine measures, including barriers, detection equipment, and depth charges. They also started moving merchant ships in convoys, so that they could protect each other.

The U-boats remained the most powerful submarine force throughout the war. But by the end, they were taking heavy losses from the convoys.

Mutiny and Scuttling

The Allies were dominant at sea throughout the war. This crippled Germany’s imports and slowly strangled German industry, and it was a major factor in the eventual Allied victory.

In the final days of the war, the German navy mutinied in protest against the conditions in the country. This sparked off wider unrest, causing domestic chaos and hastening the war’s end.

Under the terms of the armistice, the German navy was interned by the British. Rather than let their enemies have their ships, the crews scuttled them. On the 21st of June 1919, the German navy sank beneath the waves at Scapa Flow in the Orkneys. The age of dreadnoughts and battlecruisers was over. But technology would still dominate at sea, and the age of the submarine had only just begun.