Fought in May and June 1915, the Second Battle of Artois was a significant engagement of WWI. Launched by Marshal Joffre, the French Commander-in-Chief, it was an attempt to throw the Germans off French soil. Despite some successes, it achieved little militarily. Its biggest impact was a political one, as it led to a scandal that changed the British government.

In the Shadow of Ypres

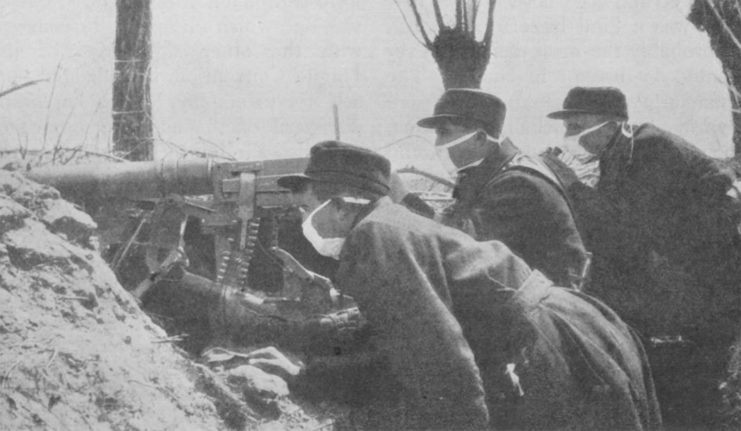

May 1915 was a bleak time for the Allied forces on the Western Front. Nine months on from the start of the Great War, they were bogged down in trenches across northeast France and southern Belgium. In April the Germans had launched a massive assault against the Allied positions in the Ypres Salient. In the Second Battle of Ypres, gas weapons had been used extensively for the first time. The Allies lost a large portion of the salient amid fierce fighting that cost many lives.

Marshal Joffre was less concerned with the poor Belgian town of Ypres than with what was happening further south. There, German forces occupied part of France. It was a blot on French pride, a situation where French civilians were living under German rule. It had to be dealt with.

As the Second Battle of Ypres was grinding toward its bloody conclusion, Joffre planned another attack – an attempt to drive the Germans out of Artois.

Pétain’s Advance

The Second Battle of Artois began on May 9.

For the previous four days, French artillery had been softening up the German positions. 690,000 shells were fired from 1,000 guns, battering the German trenches between Arras and Lens.

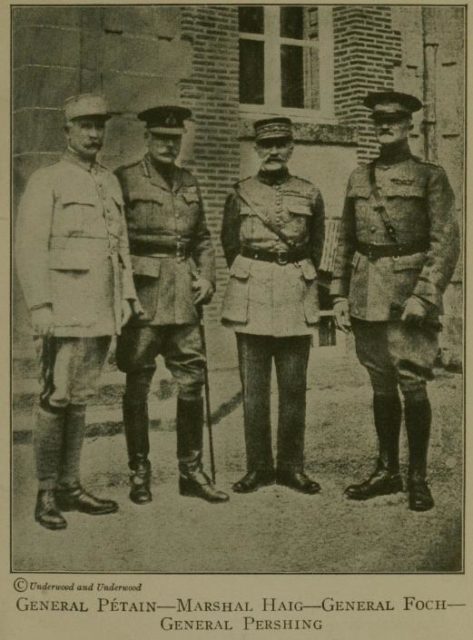

Joffre sent General Auguste Dubail and the Tenth Army into the attack. Their primary focus was a six-mile front approaching the high ground at Vimy Ridge.

It was one of the actions that made Philippe Pétain renowned. He, many years later, became the leader of the Vichy regime during WWII. As a general in the Second Battle of Artois, he led his corps in a breakthrough that advanced three miles in the first 90 minutes. It was a remarkable achievement in the usually static trench warfare.

Unfortunately for Joffre’s plans, Pétain’s gains would be the high point of the offensive. There were not enough reserves to capitalize on the breakthrough. German reinforcements rushed up to prevent further advances.

The British Attack

Although masterminded by the French Commander-in-Chief, the Second Battle of Artois featured forces from several Allied nations. The first day included an attack by the British.

On May 9, a 40-minute artillery barrage fell on the German trenches at Aubers Ridge near Neuve Chapelle. It was a relatively light bombardment by the standards of the war. Most generals believed massive bombardments were the best way to soften up their enemy before an attack. As the British were short of shells, they had to make do with a brief barrage.

After the barrage, British infantry advanced to attack the German lines. They discovered the trenches were mostly intact and the Germans ready to face them. It was far from the easy fight Haig had intended. He called off the attack, but not soon enough to save 11,500 British soldiers from dying in two days of futile fighting.

The German Defence

While the shell shortage was blamed for the British troops’ difficulties, it was more a German victory than a British failure.

The Germans were getting ahead of the Allies in their thinking about how to fight the war. They were digging deeper trenches and bunkers where they could take shelter during barrages. They could then emerge after the shells stopped falling, to fight off the Allied infantry. It was an approach both sides adopted, yet British planners seemed incapable of understanding that it would stop their attacks.

The Germans were also developing the tactics of defense in depth. Troops did not try to hold the front line when the Allies attacked. Instead, they pulled back to a second line. Then they would counter-attack once the Allies had emerged from behind their artillery cover. It reduced their losses while preventing the Allies from taking and holding German trenches.

Second Assault

At Joffre’s request, Haig launched another attack on the 15th south of Neuve Chapelle. A four-day barrage had pounded the Germans before the infantry attacked.

The British made some advance, although the result was minimal. By the time the fighting ended on the 25th, they had driven the Germans back only 800 yards. In doing so, they had suffered 16,500 casualties, compared with 5,800 on the German side.

Fighting to a Standstill

Meanwhile, the Germans had fought the French to a standstill. From May 9 to 15, fierce fighting continued between the two sides near Vimy Ridge, as the French sought another breakthrough. There was a second period of intense combat between June 15 and 19, again to little advantage for anyone involved.

The lines once more settled into the static siege warfare of the trenches. The French offensive officially ended on June 30. By then, Joffre’s men had suffered around 100,000 casualties. Pétain’s three-mile advance on the first day remained their greatest achievement.

The Shell Scandal

In London, it was Haig’s assault on the first day that drew the most attention.

Herbert Asquith’s Liberal government had severely underestimated the supplies British troops needed to fight the war. His opponents arranged an article in The Times on May 14 blaming him for the British failure. The resulting Shell Scandal discredited Asquith as Prime Minister. He was forced to create a coalition government that included his Conservative opponents.

The Second Battle of Artois did little to change the Western Front but it transformed the British government.

Source:

Ian Westwell (2008), World War I