Occasionally in history, an individual will come along whose story is almost too inexplicable to be true. To be a runaway youth in early 1900s Georgia one minute and a World War I fighter pilot for the French the next would be quite a story to tell if nothing else remarkable ever occurred throughout the rest of your life.

However, history had a way of finding Eugene Bullard or perhaps, he just had a way of thrusting himself right into the middle of it. Transatlantic stowaway as a teen, prizefighter in England, decorated member of the French Foreign Legion, and the first African-American fighter pilot to take to the skies is not too shabby of a resume to throw on one’s gravestone.

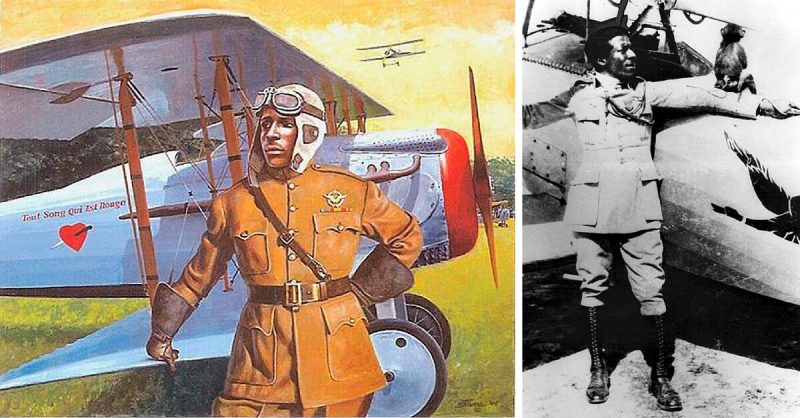

Nicknamed the “Black Swallow of Death”, this is the inexplicable story of Eugene Bullard.

A Hard Road to War

Born in 1895 Columbus, Georgia, Eugene Bullard would learn early on and from first-hand experience the discrimination facing African-Americans in the Deep South during that era. Somewhere around the age of nine or 10 years old, Bullard ran away after watching his father nearly become lynched by a mob.

Heading north and making money any way that he could, which included proving to be a quite accomplished drummer, Bullard was content to grow up at the school of hard knocks. And while he would survive on his own quite well in America, his intent was always to make his way to Paris. He recalls his father telling him that Paris was a city where the color of his skin would not matter.

During his teen years, Bullard hopped on a transatlantic steamer headed for Scotland as a stowaway. Once in England, he would continue to earn money picking up odd jobs and learning new trades as they came along. However, after working jobs at a gymnasium, his friendly disposition, and warm demeanor quickly made him friends with the boxers that trained there.

In a short time, they began to train a young Bullard and by 16 years old he began winning fights as a welterweight. After becoming noticed as quite the accomplished fighter, Bullard had the opportunity to fight in Paris and after finally seeing his beloved city he knew this would be his home.

In early 1914, Bullard would make his way back to Paris but this time for good. However, as fate would have it, this meant Eugene Bullard had arrived just in time for the Great War. Initially too young to enlist, Bullard had to sit by and watch as many of his friends became casualties of what the world was realizing was going to be a very costly war.

By late October, Eugene Bullard would join other expatriates living in France and become a member of the highly esteemed French Foreign Legion. Becoming a machine gunner, Eugene Bullard would prove to the Germans that this boxer knew more than one way to fight.

The Croix de Guerre

Bullard was initially assigned to the 1st Moroccan Division of the French Foreign Legion. Here he would participate in some of the heaviest fighting of the war. The Legion suffered high casualties in 1915 due to their willingness to attack any position and their refusal to surrender. By late 1915, the Legion would undergo massive reorganization and Bullard’s particular unit was essentially disbanded.

Being an American, he was allowed to transfer to the 170th Light Infantry Regiment of the French army. Nicknamed “The Swallows of Death” the 170th would take Bullard into the fighting at Verdun in early 1916 and serve as the inspiration for his self-proclaimed nickname.

On March 5, 1916, Bullard would be seriously wounded at Verdun in an action that would award him the Croix de Guerre. In recovery, some thought Bullard would never walk again. However, this was just another obstacle for Bullard to overcome. No longer able to serve in the infantry, Bullard jumped at the opportunity to join the French Air Corps.

After flight training on the biplanes of the era, this elementary school dropout and runaway from a small town in Georgia will become the first African-American fighter pilot in history. Assigned to the Lafayette Escadrille, he would fly the famed Nieuport and Spad biplanes.

He flew his first mission on September 8, 1917, as a reconnaissance mission over the city of Metz. All in all, he would fly 20 combat missions in World War I and claimed two kills. And while they were not officially verified according to the standards of the day, few doubted that he indeed shot down those planes.

Unfortunately for Bullard, a November 1917 quarrel with a French officer who found out the hard way that Bullard was an accomplished boxer ended his flying career. He was sent back to the 170th where he would perform non-combat duties throughout the rest of the war. But having been wounded four times and becoming the first African-American fighter pilot in history with a reported two kills made for a pretty reputable war record.

After the War

In keeping with Bullard’s tradition of living a remarkably fascinating life, he would remain in Paris after the war where he would perform as a drummer in jazz clubs while being somewhat of a local celebrity. He would eventually become part owner in the nightclub, Le Grand Duc, where he would become friends with all the jazz greats of the day who toured Paris to include Josephine Baker and Louie Armstrong. During the years prior to World War II, he is reported to have worked as a French spy in the nightclub reporting on German agents who would visit the venue.

When the Germans invaded France in May 1940, Bullard and his two daughters fled West. Never afraid of a fight, Bullard volunteered for the 51st infantry defending Orleans. But after being seriously wounded, he finally returned to the United States eventually settling in New York.

While he was a highly decorated veteran of World War I in France, his fame would unfortunately not follow him to the United States. He worked a variety of odd jobs in the United States before finally becoming an elevator operator at Rockefeller Center.

It is unlikely that those he ferried to the top floors had any idea that they were ascending with the “Black Swallow of Death” as his final years were spent in relative obscurity.

He passed away in 1961 due to cancer and was buried with military honors in the French Veteran’s War section of Flushing Cemetery in Queens. And while he might have passed away in obscurity, the history of war ensures that those who display inexplicable gallantry against heavy odds will always be remembered as an inspiration for the next generation who might be called upon to do so.