Many probably don’t realize that what they’ve learned about history, especially when it comes to WWI, is not necessarily true. Here are the top 10 misconceptions about WWI:

The Schlieffen plan allowed Germany to invade Belgium and France

Although it is true that the Germans intended to use what was called the Schlieffen plan, in practice, the plan was changed by the strategy of Helmuth von Moltke. Keeping the right flank strong was the focus of Schlieffen’s strategy, which would demolish the Allied forces in the north while luring the French into undefended German territory and directly into envelopment from the strong right flank.

Moltke, however, drew forces away from the right flank to reinforce German territory and defend it from an attack from the west, which divided forces into two weaker flanks instead of one strong one.

The plan is still argued about today between historians. While some believe Schlieffen’s plan would have worked if Moltke hadn’t meddled, others believe the plan would have failed with or without Moltke’s changes.

However, it is true that Moltke’s version certainly didn’t work. The Germans advanced through Belgium and northern France against the Belgian, British and French armies and reached an area 30 kilometers (19 mi) to the north-east of Paris, without managing to trap the Allied armies and force a decisive battle on them.

The German advance outran its supplies and Joffre was able to use French railways to move the retreating armies and re-group behind the river Marne. They did this faster than the Germans could pursue and the French defeated the faltering German advance, with a counter-offensive at the First Battle of the Marne, assisted by the British.

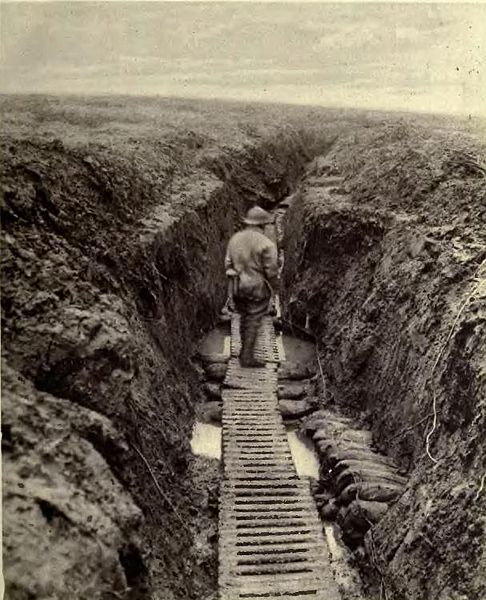

All of the fighting happened in the trenches

This may have been true for a while in the west. After the First Battle of the Marne and the Race to the Sea, the war turned into aggressive trench battles on this front. A majority of the fighting stayed that way until 1918 when the German army was depleted and close to giving up.

But in the fighting in the east and south, and mostly because of the landscape, troops fought on the move. The battles that took place in Prussia, Poland, and Ukraine took place along an extended front, so they never were in the trenches for a long time.

Russian General Alexsei Brusilov had developed tactics by making broad-front deployments that forced the enemies to spread out, covering a wider front. And battles that were taking place in the Italian offensive during 1916 and 1917 forced soldiers to fight on the Alpine glaciers, mountains, and even caves.

All trench warfare involved “going over the top.”

While trench warfare did consist of waves of soldiers coming out of the trenches when ordered, there was much more to it than that. Artillery barrages, increased reliance on air warfare, flexible defensive configurations, and use of stormtroopers were more highly-efficient tactics for targeting the weak points in enemy lines.

Soldiers lived in the trenches for long periods

A soldier usually never stayed in a trench for longer than three days at a time, being regularly rotated due to the harsh conditions there. To improve morale, troops were never put in the first line trenches for very long, being moved further away from the fighting as time went by.

For example, during the Battle of Verdun, French troops were moved down a four-line series of trenches once a week for a one-month cycle. British troops spent ten days per month in the trenches; only three days were spent in the front line trenches.

World War I was a single, coherent conflict

Generally, people think of the WWI as two forces fighting for supremacy. But it became more than that as different countries were moved to enter into conflict for different, individual reasons.

Besides being a bid for hegemony against an attempt to stop this aggression, the war involved another rationale in other areas, including imperialistic expansion and sociological revolt.

Most men were killed by machine guns

Although it is true that during WWI machine guns were put to deadly use, ever since the American Civil War men have been confronting the enemy with an impenetrable wall of bullets.

The big change in WWI was the use of artillery, which claimed nearly two-thirds of all of the casualties. On some days nearly 40,000 shells might be fired.

The war in the desert was made up of isolated skirmishes

This is entirely false. Isolated insurgent skirmishes were made popular by T. E. Lawrence and the movie Lawrence of Arabia, but were never the whole story of the fighting in the desert campaign.

Archeologists are still uncovering facts throughout the desert to support whether or not the Lawrence stories were true. What is known is that by 1918 the desert war was a large and impressive operation that included the use of Arab regular forces, light armor, truck-mounted artillery, an increasingly sophisticated use of artillery and support weapons, and the integration of aircraft.

The tactics were a precursor for the strategy of desert war during WWII.

Lions led by donkeys

During WWI many countries had to change their fighting tactics, forcing the generals to abandon their favorite strategies and fighting techniques; stepping back, rethinking the tactics, and coming up with new ones when needed.

Sometimes this would give the impression that they were incompetent or weak. But the generals’ goal was not only to win battles but also to preserve their forces. New, deadly technologies such as the introduction of aircraft, tanks, and unfamiliar defensive and siege techniques forced the generals to adapt quickly and, in the process, appear to have been undecided.

The battle that many use as an example is the Battle of Somme. It was, and still is, dubbed one of the worst catastrophes of WWI. However, this very battle shows just how much war had changed and evolved in just two short years since the start.

Many chalked the massacres up to incompetent generals. However, they did not take into consideration that the generals who were thrown into battle did not understand the need for updated techniques.

It was the deadliest war until the start of the Second World War.

It is still not certain today just how many men lost their lives in the war. Historians are still trying to figure out the exact numbers, but the estimated death toll is from 9 to 17 million people, counting military and civilian deaths.

This is devastating, and a great tragedy but those who think it’s the biggest human loss in war history are mistaken. One historian points out that one ancient war alone, China’s 14-year Taiping Rebellion from 1850 to 1864, claimed 20 to 30 million human lives.

The First World War was futile

It is understandable to feel, now that we can look back on it, that nothing was gained or altered because of WWI. After a cost of millions of military and civilian lives, and after all the destruction and waste of national treasure, it’s often claimed that, politically, the war made no real difference in the world.

What’s needed is a look into the future as if the war had come out with anything less than a full Allied victory. The 20th century would be a drastically changed setting in a vastly different geopolitical venue. The fact that it seems like the whole thing had to be redone with the onset of WWII a generation later makes the trials and agonies of the first world war look like a total failure, but that was mostly a lack of the victor’s will to enforce the treaty that ended it.