The biggest, most advanced, most expensive, and most daunting war machinery of World War I was the super-dreadnought battleship. These great sea beasts were near unsinkable and, in fact, only one was sent to the bottom during the entire war. And it was practically sunk by mistake, at that.

This ship, the British HMS Audacious, was a King George V-class battleship, the peak of naval size, power, and capability and it barely made it off the shores of Britain. Imagine the Kaiser’s delight.

The naval power of Britain and Germany was a very contentious area during and leading up to WWI. Before air power was seen as crucial, ruling the waves was the key to controlling an empire out of Europe. Bismarck had actually warned the Kaiser not to build up the German Imperial Navy to such a great strength for fear that the British, by far the naval powerhouse of the age, would notice and act accordingly.

The HMS Audacious was laid down in 1911, launched in 1912, commissioned to the 2nd battle squadron in 1913, and on October 27th, 1914, was sent out for gunnery exercises in preparations to meet the Imperial German Navy in the great war.

Several years earlier, in 1906, the HMS Dreadnought was launched. This ship had massive guns, steam turbine propulsion, massive, heavy armor, and instantly became the terror of the seas. Battleships that were built before this became simply known as pre-dreadnought class. Some advancements, including 2,000 tons more displacement, even bigger guns, and the placement of these guns on the centerline of the ship, which came five years latter with the Orion Class ships, introduced the next level of behemoths known as super-dreadnoughts.

The HMS George V made some improvements to the Orion and it was in this fashion that the Audacious was built.

The Audacious had 23,400 long tons of displacement, 10 13.5” guns, 16 4” guns, 3 21” torpedo tubes, and Krupp armor up to 12” thick. This armor wasn’t always continuous, however, and much thinner in some places, which would be the ship’s downfall.

The Audacious carried a crew of 900. One improvement these King George V class battleships had over the Orion class was that the foremast was put ahead of the first smoke funnel, so visibility from the firing platform was vastly improved.

The total cost of the Audacious was £1,918,813, which would be over £200 million ($300 million) today.

Under the command of Captain Cecil F. Dampier, the Audacious left Lough Swilly in Scotland early in the morning for its gunnery exercises North of Ireland with six other super-dreadnoughts, including the King George V and the Orion. At 8:45, as the ship was turning, it struck a German mine.

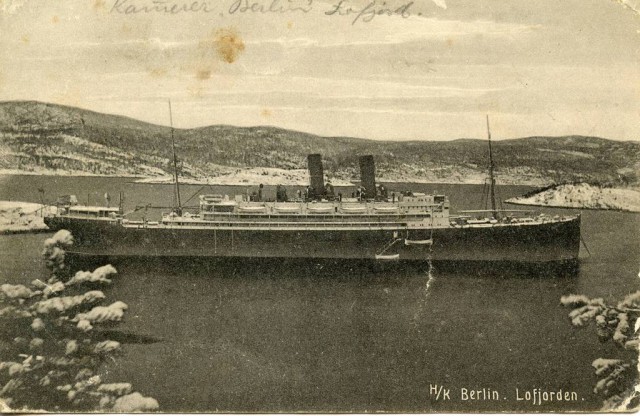

A few days earlier, the German ship SS Berlin, a passenger liner recommissioned as a mine-laying vessel for the war, had laid a minefield right in the British shipping lane that runs between Ireland and Britain and through which crucial Atlantic travel and trade traversed.

The Berlin had been ordered to slip past the British sea blockade and lay mines in crucial areas the British were docking their ships on the West coast of Britain in the Firth of Clyde. Captain Pfundheller managed to guide the Berlin to the West coast, but couldn’t get close enough to his targets for fear of being discovered. He settled for mining the shipping lane and sailed off.

This, oddly enough and despite its success, was a failure which lost Captain Hans Pfundheller his command as he, due to lack of fuel, had to sail to the neutral port of Trondheim where he, his crew and his ship were interned for the rest of the war.

Two British merchant ships struck mines and sank, but the Admiralty didn’t hear the news in time before the Audacious and its battle squadron sailed through.

When the Audacious first felt the blast of the mine, Captain Dampier, fearing a German U-Boat assault, sent up the signal, and the rest of the Squadron steamed away.

Audacious attempted to limp its way the Ireland and beach there, but water continued to flood in and by 11:00, the central turbine was submerged. By 14:30, Captain Dampier had ordered all non-essential crew off the ship.

As fate would have it, the RMS Olympic, of the same White Star line as the Titanic, was sailing through and offered to tow the massive battleship. But the ship was too unmanageable and the tow line parted.

At 17:00, Commander-in-Chief of the Grand Fleet Sir John Jellicoe, heard news of the ships that had been sunk by the minefield the previous day and night and, though he had only ordered destroyers and tugs to assist the Audacious before, now was sending larger ships to assist.

All efforts were in vain, however, and at 19:15, with night falling, Captain Dampier, and the remaining crew abandoned ship.

At 20:45, the Audacious capsized. At 21:00, a massive explosion tore through the vessel and shook the seas. There were 474,800 lbs. of explosives on the ship. The blast sent shrapnel thousands of yards. On the light cruiser HMS Liverpool, 800 yards away, a petty officer was struck by an armor plate and killed, the only causality of the the whole incident.

British command quickly put full restrictions on any reporting of the Audacious’ sinking. Through the remainder of WWI, the British kept the ship on public lists of movements and activity. In 1918, the Secretary of the Admiralty released a “delayed announcement” of the sinking and even noted that the press “loyally refrained from giving it any publicity.”

Unfortunately, the Olympic had been carrying passengers from America. Many people took pictures and even motion film of the event who weren’t under British authority. By November 19th of that year, German Admiral Reinhard Scheer had heard word of the Audacious, but after the war commended the British for not wanting to reveal weakness and hide from their enemy their true strength and abilities.