When does the attempt to defend oneself, one’s property or the men and the women under one’s charge from capture – or worse – become an offence serious enough for execution? This conundrum has kept legal minds arguing the pros and cons since Captain Fryatt found himself in precisely that situation.

Charles Algernon Fryatt, a married man with seven children, was born in 1872. His family moved to Harwich in Essex, where he completed his schooling, after which he joined the Mercantile Marine, serving on a number of ships before joining the Great Eastern Railways as a seaman. He rose through the ranks, receiving his first command, the SS Colchester, followed in 1913, by becoming the master of the SS Newmarket.

An experienced mariner by the time of the 1914-1918 World War, Captain Fryatt had completed over 140 passages between England and the European continent. Initially, although ever-present, the U-boats were not threatening, but the situation soon changed. During March of 1915, a British mail ship was sunk with much loss of life, and Captain Fryatt himself had two tangles with German U-boats. The U-boats began targeting Merchant shipping, mainly to prevent supplies from reaching Britain, but also in retaliation for the tight British blockade which prevented vital supplies reaching Germany.

The first skirmish occurred on March 3rd, when, as captain on SS Wrexham, Fryatt was chased by a U-boat for the 40 miles it took to reach the safety of Rotterdam. Fryatt called on his crew to exert themselves to their utmost to reach a speed of 16 knots, (the maximum limit was 14 knots) and the SS Wrexham arrived safely, but with funnels burnt and blistered. For this brave act, Fryatt was awarded a gold watch by the company, and the whole crew was commended for the outstanding effort.

The next attack experienced by Fryatt, was on the 28th of March, as captain of the passenger ferry, SS Brussels. They were close to the Maas Light-Vessel off the Dutch coast when they saw the surfaced German submarine, U-33, which ordered them to stop. Fearing it was preparing to fire a torpedo, and with the safety of the ship, crew and passengers in mind, Fryatt decided to attempt ramming the U-boat head on, forcing it to crash-dive. The SS Brussels was thus able to escape and made it safely to port. For this extremely brave deed, Fryatt was awarded a gold watch by the Admiralty as well as a certificate in vellum by the Lord Commissioners of the Admiralty and furthermore, was praised in the House of Commons.

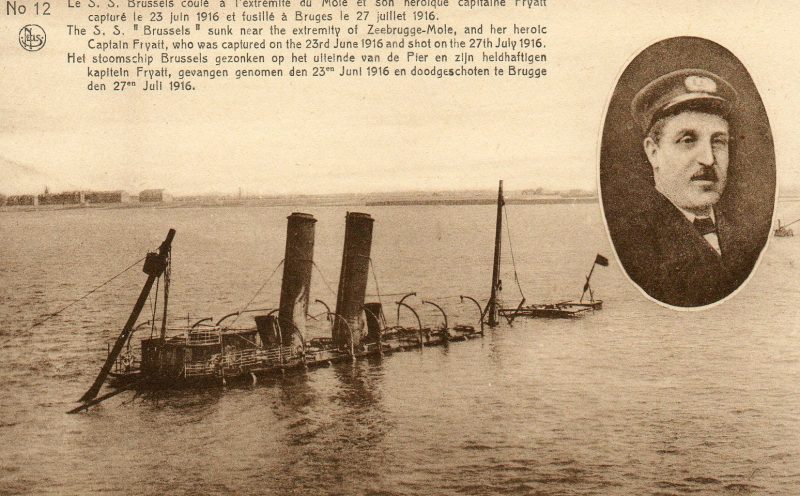

Sailing from the Hook of Holland the following year (23rd June 1916), some German destroyers surrounded the SS Brussels and took possession of the ship. Fryatt, his crew, and his passengers were taken prisoner and the ship was sailed to Zeebrugge.

Fryatt, after intense interrogation was taken to the Town Hall of Bruges, where he had to face a Court Martial on charges of being a ’franc-tireur’ – a civilian engaged in the hostile military activity. His gold watch from the Admiralty was used as evidence against him, and he was accused of sinking the German submarine U-33, although it appears it was still in service at the time. The hearing, the sentencing to death and his execution by firing squad all took place on the same day – the 27th July 1916.

His death was used for propaganda purposes by both the Germans, who maintained that justice had been served, as well as the British who used this ‘murder’ to increase their recruitment rate, while also turning international opinion against Germany, by advertising this awful ‘justice.’ It turned many against the ‘terrible Huns’ and it is said that many British-fired shells aimed at the Germans had ‘Fryatt’ written on them.

The Admiralty had issued an instruction that crews should try to ram U-boats in an attempt to get them to submerge, for a submerged U-boat could not use its deck guns, was slower underwater and would be unable to get alongside a merchant ship to board it. Furthermore, torpedoes were neither very reliable nor accurate and so would be more likely to miss a beam view of a ship than a broadside view. Thus, attempted ramming of submarines by merchant ships was not uncommon.

However, says Mark Baker, organiser of the exhibition on the centenary of Fryatt’s death, says: “It is still very, very controversial … It’s a case that has exercised legal minds ever since… Merchant mariners’ rights to defend themselves in open water is still very much a grey area.”

Captain Charles Algernon Fryatt has joined the ranks of those very brave men who gave their lives for others during WWI, and as such he has not been forgotten. After the war, his body was brought back to England where he was given a state funeral with all due honours. He was then re-buried at the All Saints Church in Dovercourt, beside a walkway overlooking the harbour, with a headstone on which appears the following inscription: ‘In memory of Captain Charles Algernon Fryatt, Master of the Great Eastern Steamship, Brussels, illegally executed by the Germans at Bruges on the 27th July, 1916.’